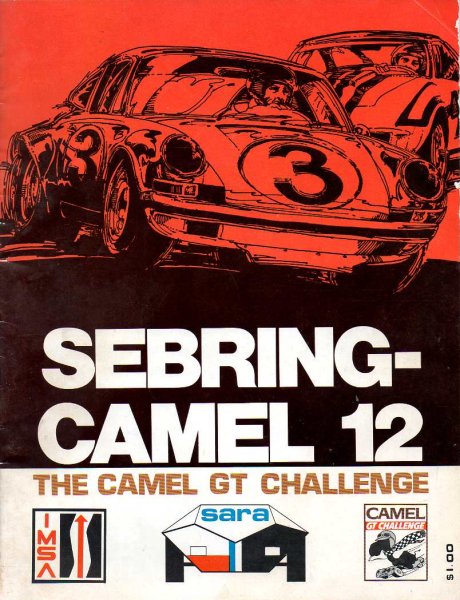

I get asked often: “What was the first IMSA GTP car?” While most people think it was the BMW M1/C that showed up at Riverside in 1981, the truth is a bit more complicated. Yes, the BMW-March was the first prototype purpose-built to the new IMSA GTP rules published in 1980, but it was not the very first race car to run in the GTP class at a Camel GT event. But before we get to that story, first some background.

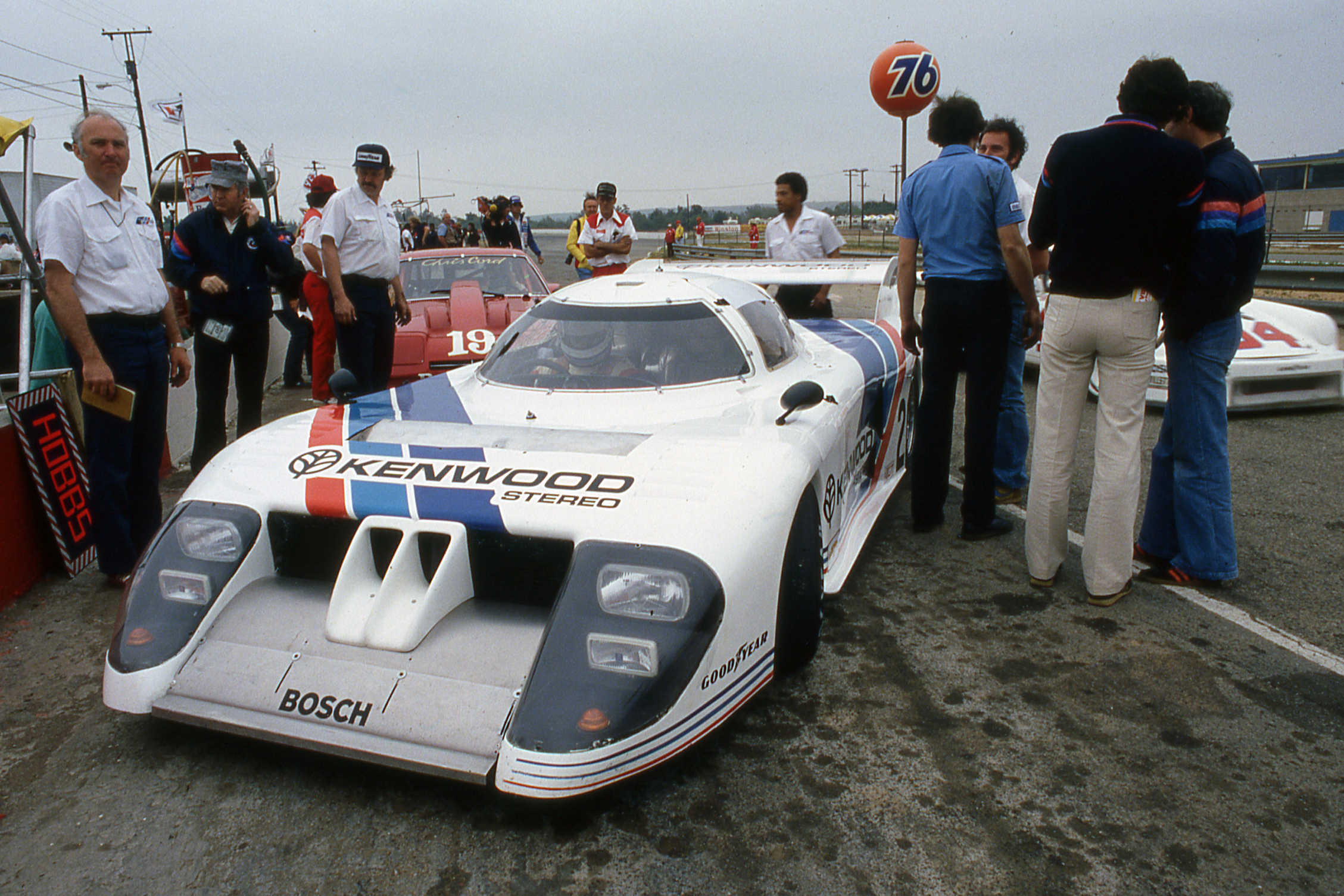

The BMW M1/C debuted at Riverside in April 1981 with David Hobbs driving. The March chassis featured a modern aluminum monocoque that was mated to a normally aspirated 3.5-liter BMW engine. The team would upgrade to a 2.0-liter turbocharged motor later in the year. Photo: Don Hodgdon

The Porsche 935 was dominating the 1979 IMSA season. Although the racing was close, IMSA president John Bishop worried that no one would continue to pay to see a Porsche parade. The All-American GT (AAGT) concept had diversified the fields for a while, but the cars were increasingly uncompetitive against the onslaught of 935s, even with more relaxed GTX rules that allowed for tube frames, wider wheels and essentially unlimited bodywork. BMW, Nissan, and Ford had all been represented in the GTX class during this time, but only as solo or two-car efforts; there were no customer cars. And the price of a new Porsche 935 was in excess of $200,000, a huge sum at the time. Privateers were getting priced out of the game.

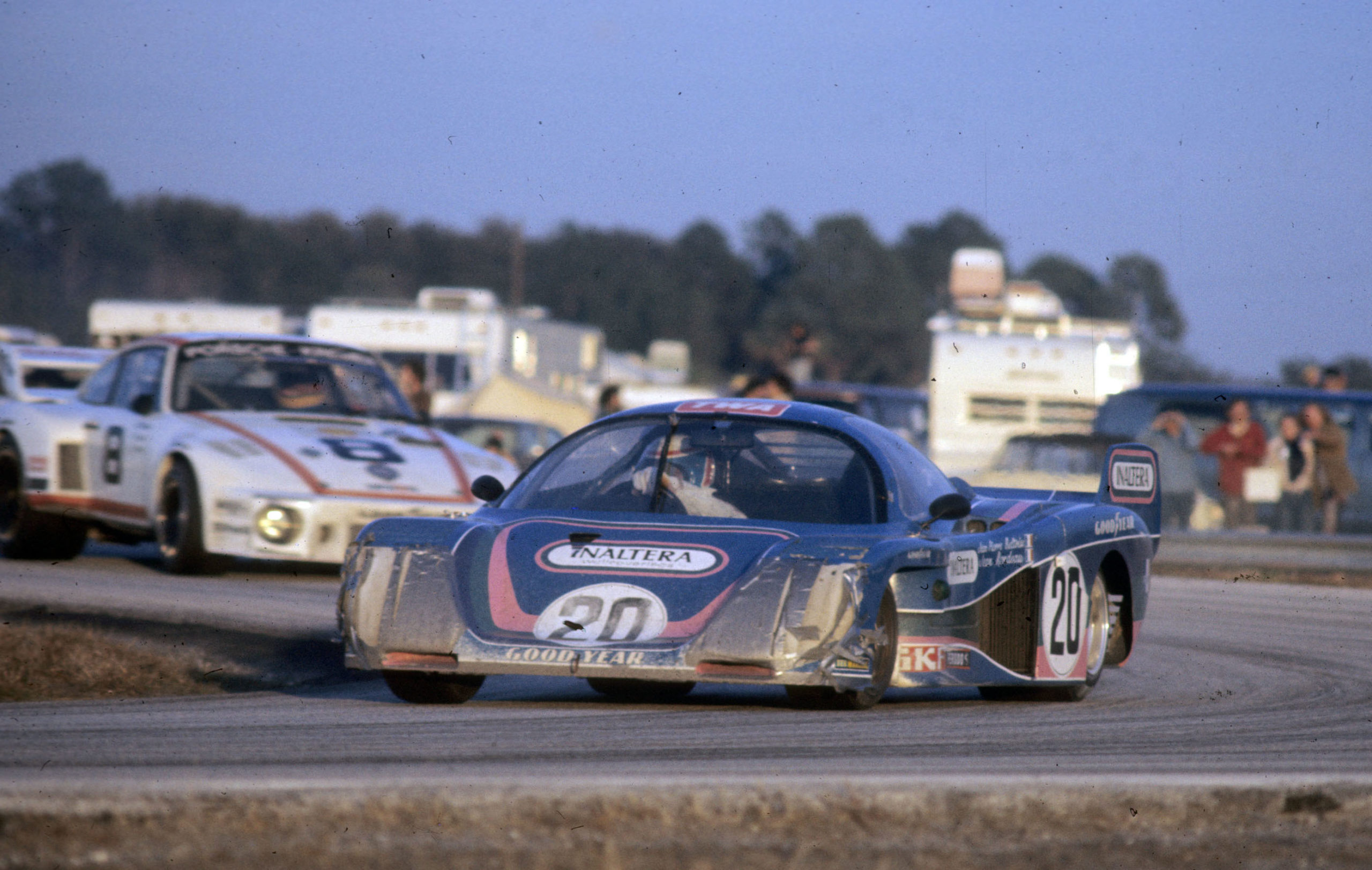

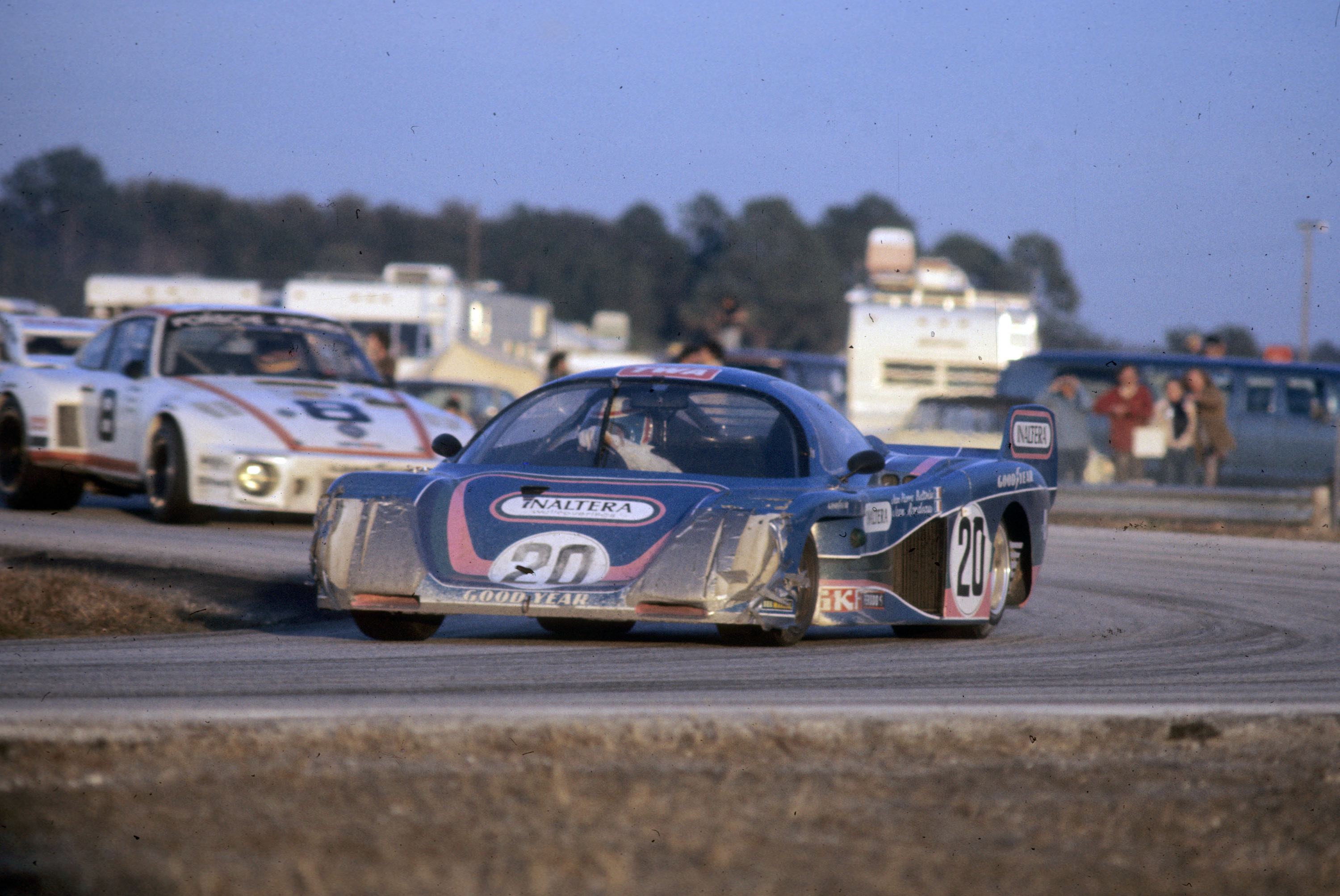

One of two Inaltera “Le Mans GTP” class cars during the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1977. The privately designed and built machines became the inspiration for the IMSA GTP class rules developed in 1980. Photo: autosportsltd.com

“We were initially inspired by the Inaltera cars that showed up for the 1977 24 Hours of Daytona in a special LeMans GTP prototype class,” Bishop continued. “The cars were fast, good looking, and competitive. Best of all, they were built with off-the-shelf parts by Jean Rondeau, a private entrant in his garage, so we knew it could be done on a reasonable budget. Given the availability of a wide variety of reliable engines, our vision was to repeat a bit of the same formula that had made the AAGT class such a success. Our goal was to create a prototype class that could compete head-to-head with the 935s but at a lower price point.”

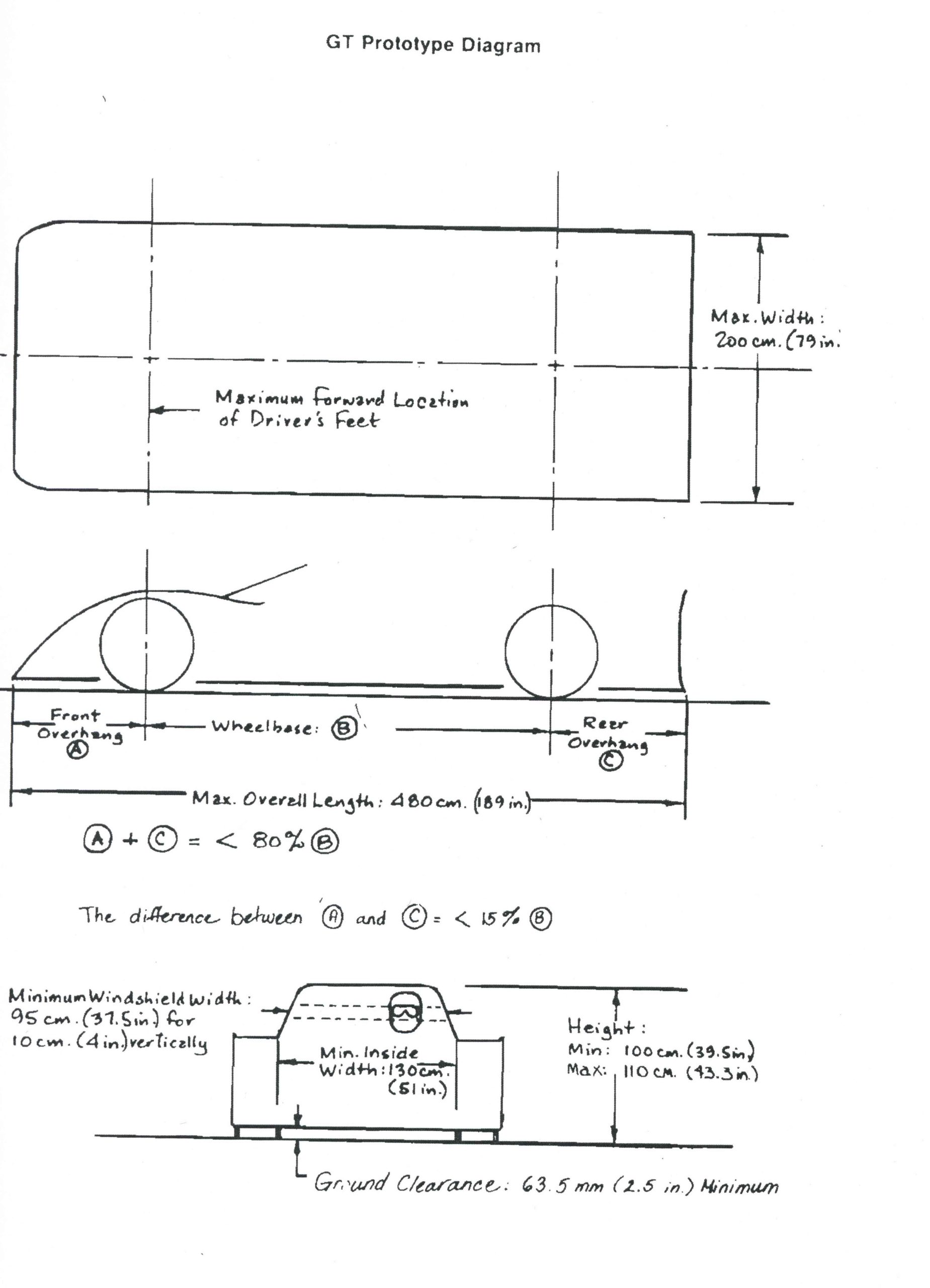

Unlike FIA Group C, which focused on a fuel consumption formula in its rules, IMSA GTP used a sliding scale of weight versus displacement to accept as many engines as possible and give entrants freedom to decide what chassis/power package would be most competitive. The initial GTP rules set a sliding scale for cars weighing 700kg, 800kg, and 900kg using corresponding production-based, stock block engines rated at 400bhp, 500bhp, or 600bhp. This provided a place for just about everything from 335bhp Mazda rotaries to 650bhp Detroit V8s to compete on a level playing field.

The technical rules for the IMSA GTP class were kept simple in an effort to attract as many different chassis and engine manufacturers as possible. John Bishop’s hand-drawn diagram of GTP dimensions became a fixture in the IMSA rule book. Source: IMSA

“Roger Bailey deserves much of the credit for the GTP rules,” remembered Bishop. “We developed a formula where basic pushrod engines would be our yardstick. Any sophistication in the engines would then create a handicap as they got bigger, so we added weight to keep things even. If an engine had four valves per cylinder, then it had to weigh something like 1.3 times the version with two valves. We took a lot of time and care to conscientiously come up with the fairest possible set of rules that also included turbocharged engines.”

With the new IMSA GTP rule book in place by early 1980, various efforts were started at Lola Cars, BMW-March and other manufacturers to design cars. But others were at work as well.

The very first car to run in the GTP class at an IMSA race was Jim Busby’s highly modified BMW M-1 at the 1980 Road Atlanta Camel GT race in April. As Busby tells it: “The March-BMW M-1 we raced at Daytona and Sebring that year was a disaster against the 935s. We were down on power and stuck with an unreliable package. So, we stuffed a Traco Engineering Chevrolet V8 in the thing and called it a March M-1 Chevy. We couldn’t run it as a BMW or an M-1 anymore; it certainly wasn’t homologated. We asked John Bishop about it ahead of time to make sure IMSA would let us run, and he winked and said it was fine. The car had a solid monocoque, two seats, and a large, American-made V8, so IMSA let us run it as a GTP car.”

The first car ever to be classified as “GTP” in an IMSA race was a Chevrolet-powered BMW M-1 entered by Jim Busby at Road Atlanta in 1980. Seen here at Riverside, the car turned out to be a beast to drive and was abandoned the next race weekend at Laguna Seca. Photo: Kurt Oblinger

The Busby March M-1 Chevy dropped out of both the Road Atlanta and Riverside rounds and turned out to be an unholy terror to drive. Busby had a major off at Laguna Seca in Saturday practice the week after Riverside. The car scared him so much that he threw in the towel and purchased a Porsche 935 from Gianpierro Moretti on the spot and raced it at Laguna the next day.

At the inaugural race of the 1981 season, the first prototype GTP car showed up for the 24 Hours of Daytona. Working largely in his own garage, longtime IMSA competitor Del Russo Taylor spent the better part of 1980 marrying a Chevron B19 chassis with an Alfa Romeo V8 engine. Since the Chevron was designed as an open cockpit sports prototype, he used a Corvette rear window as his mandatory front windscreen. To improve safety, a second roll bar was welded into the chassis next to the original. Hand-crafted sheet metal completed the makeshift roof. The result was less than aesthetic, but the car proved the fundamental point of the new rules. Here was a private entrant with ingenuity that assembled a fast prototype using readily available parts.

The first purpose-built GTP car entered in an IMSA event was Del Russo Taylor’s converted Chevron B-19 with an Alfa Romeo engine that first arrived at Daytona in January 1981. It would practice, but not compete in the race. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

At Daytona, the car was so slow, especially at night, that IMSA reluctantly told Taylor he couldn’t race. Taylor went home, worked some more, and turned up at Sebring six weeks later, where he finished 51st, completing just 72 laps. The car was called an Alfa Chevron for that race, but a Buick V6 was installed for subsequent events. Taylor ended up running the car for several years in the GTP class, at times with impressive speed, including a fifth-place at Mosport and a sixth at Lime Rock in 1982.

“The first time I really got a good look at that car was when we pulled into the paddock at Sears Point and I noticed what looked like the remains of a massive wreck laid out on the cement in a circle about 40 feet wide,” recalled Bishop. “Roger Bailey was with me and he said: “I sure hope no one got hurt in that wreck.” Turned out, it was simply Taylor’s car in pieces, complete with oil stains, in the middle of an engine change”

Just to confuse the matter further of which was the first IMSA GTP car, there was another entry that showed up at Daytona in 1981 that ran either in the GTP or GTX class depending on which story you believe. McLaren Engines in Michigan built a Ford Mustang fitted with a 2.0-liter normally aspirated Cosworth racing engine. Dubbed a “McLaren Mustang,” the car ran on shaved Firestone HPR street tires and contained a few other trick parts like a unique Halibrand Sprint Car quick-change differential and a live rear axle. Firestone sponsored the entry as part of an effort to promote their high-performance street tires. Ford Performance had nothing to do with the effort, according to then team manager Roger Bailey. The original intention was to race the car in the IMSA GTO class but with the non-production-based engine, the car wasn’t eligible for that class.

The McLaren Mustang’s Cosworth-based, four-cylinder engine. Photo: Ed Wheatley (current owner)

The McLaren Mustang at speed at Daytona in 1981. Note the hastily made “GTP” decal on the driver’s door along with the official “IMSA GT” decal. Photo: Ed Wheatley

This is where the two stories diverge. According to IMSA results, the car was listed as a GTX machine, running up against a host of Porsche 935s and tricked-out Corvettes. Yet the team was adamant that the car was run in GTP. The letters “GTP” were painted (or a decal was hastily created) on the driver and passenger side doors in what looked like an official IMSA font but were not put there by IMSA officials. The only official IMSA class sticker on the car was “IMSA GT” on the same doors.

It may be that the team realized that the car didn’t stand much of a chance in the GTX class and concocted a scheme to try to run the car run in GTP since there were no other cars running in GTP at Daytona in 1981. Doing so would guarantee a win for the team. It’s not clear whether IMSA officials noticed or decided to turn a blind eye to the scheme during the event but the car was eventually classified in the final results in “GTX.” The car ran well in the race but an engine change during the night relegated drivers John Morton and Tom Klauser to a 21st-place finish (8th in GTX). After the event, Ford Performance, who had been absent from the whole project beforehand, touted a “win” in GTP in their marketing materials and postcards.

The McLaren Mustang was entered in just one other race at the 12 Hours of Sebring a few weeks later, where it finished 40th after the rear axle seized out on the track, necessitating a replacement rear-end change by driver Tom Klauser and a mechanic who ran out to the car with spare parts once donning a spare John Morton racing suit to skirt the rules about no mechanics touching race cars out on course. After Sebring, the program was abandoned and the car never raced in IMSA again. It is now owned by Ed Wheatley and being restored for vintage racing.

So the answer to the question: “What was the first IMSA GTP car?” is not a simple one but it’s a most interesting topic.

-Mitch Bishop is the son of IMSA founder John Bishop and co-author of “IMSA 1969-1989,” available wherever great books are sold.

The following is an excerpt from the book, IMSA: 1969-1989, by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Once IMSA was incorporated in the summer of 1969, founder and president John Bishop turned his attention towards figuring out what kind of show the fledgling sanctioning body was going to produce. Bishop was committed to not competing with the SCCA, whose professional racing championships were dominating the racing scene; the Trans-Am and Can-Am series were arguably at the peak of their popularity. He decided to run a series of races for Formula Fords and Formula Vees on ovals, along with a few road courses. There were plenty of cars available and no professional outlet for these drivers. And key tracks were owned by benefactor Bill France, Sr. Calls were made to promoters and the first few races were scheduled.

Invitations were sent to all the top open-wheel drivers to join IMSA and come race. The immediate and positive response from drivers were encouraging and gratifying. Bishop’s name and reputation, carefully built during his tenure at the SCCA, was opening doors. The fact that IMSA was offering prize money didn’t hurt, either.

The first IMSA race was scheduled for October of 1969, a Formula Ford event on the short, 5/8-mile oval at Pocono International Raceway. A promoter’s agreement was signed, entry forms were mailed out and the race was advertised in the trade press. The entry list started building to an eventual 23 drivers and cars. Everything was going smoothly, or so it seemed.

Just two weeks before the inaugural IMSA event at Pocono, John Bishop received an urgent call from Dave Montgomery, the track president, who told him that he was going to have to cancel the race due to pressure from the SCCA. The Club was threatening tracks and workers with ex-communication if they participated in any IMSA events, a tactic borrowed from the early days of the road racing wars in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Although it was barely off the ground, the Club viewed IMSA as a potential rival. Ultimately, this approach didn’t work and was abandoned, but the short-term threat to IMSA was quite real. Track owner Joe Mattioli did agree to lease the track directly to IMSA but could not agree to do more for fear of losing SCCA dates the following year.

Deciding that IMSA’s credibility was on the line, Bishop swallowed hard, borrowed $10,000 to lease the track and solidify the prize money. He scrambled and called on friends to help with timing, scoring, pit marshal duties, technical inspection, and safety roles. The race was back on. Inverhouse Scotch came on board at the last minute to help with prize money and promotion.

NASCAR founder and original IMSA investor Bill France Sr. and John Bishop enjoy a laugh before the race at Pocono. Dick Gilmartin, IMSA’s first public relations director, is on the left. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

On October 19, 1969, the 23 teams that showed up were immediately treated to some refreshing changes from the way things were done at the SCCA. There were apples and friendly faces at registration, and prize money was awarded to everyone that started. Ray Heppenstall helped Charlie Rainville with technical inspection and they introduced another innovation; teams didn’t have to line up. Instead, Ray and Charlie went around to where the competitors were parked in the infield and did their work on the spot. It was a revelation to competitors.

Promotion for the event had appeared in Competition Press & Autoweek, but very little marketing had been done locally. Still, 350 curious spectators showed up. Everyone in the Bishop family pitched in. Peggy ran registration and worked scoring. Son Marc, on leave from the Navy, along with John’s brother Peter, sold tickets. Sons Marshal and Mitch directed traffic in the parking lot and worked timing and scoring. Drivers’ wives were also pressed into service to score the race. It was an “all-hands-on-deck” exercise. Bill France Sr. made sure to lend his support by flying in, giving the event instant legitimacy.

A rare shot of the driver’s meeting for the inaugural IMSA race at Pocono. Bill France Sr. is on the far left, wearing the hat and long coat. Jim Jenkins in on the left, in front of the window. Bill Scott talks with Carson Baird in the foreground. John Bishop is by the tow truck in the back. Fourth from the right is Don Nixon, who ran timing and scoring for the event with his wife Ruth. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

Some of the best Formula Ford drivers of the day showed up: Skip Barber, Bill Scott, Jim Jenkins, and Fred Opert, among others. Almost all of them had no experience on ovals and many guessed at the proper setup. One of the guys that guessed wrong was George Alderman, an experienced SCCA racer who backed his car hard into the outside retaining wall during qualifying, ending up in the hospital overnight with a concussion. The car was not so lucky, it took months to rebuild. Alderman came back to become an IMSA regular and won the 1971 and 1974 IMSA RS series titles.

The race itself was a 200-lap affair. The pace was frantic on the flat, 5/8-mile oval. Timing and scoring was being done from the grandstands; there was no covered area to work. The scorers, used to longer road courses, were overwhelmed by cars completing laps in just 26 seconds. It was all done the old-fashioned way – by hand.

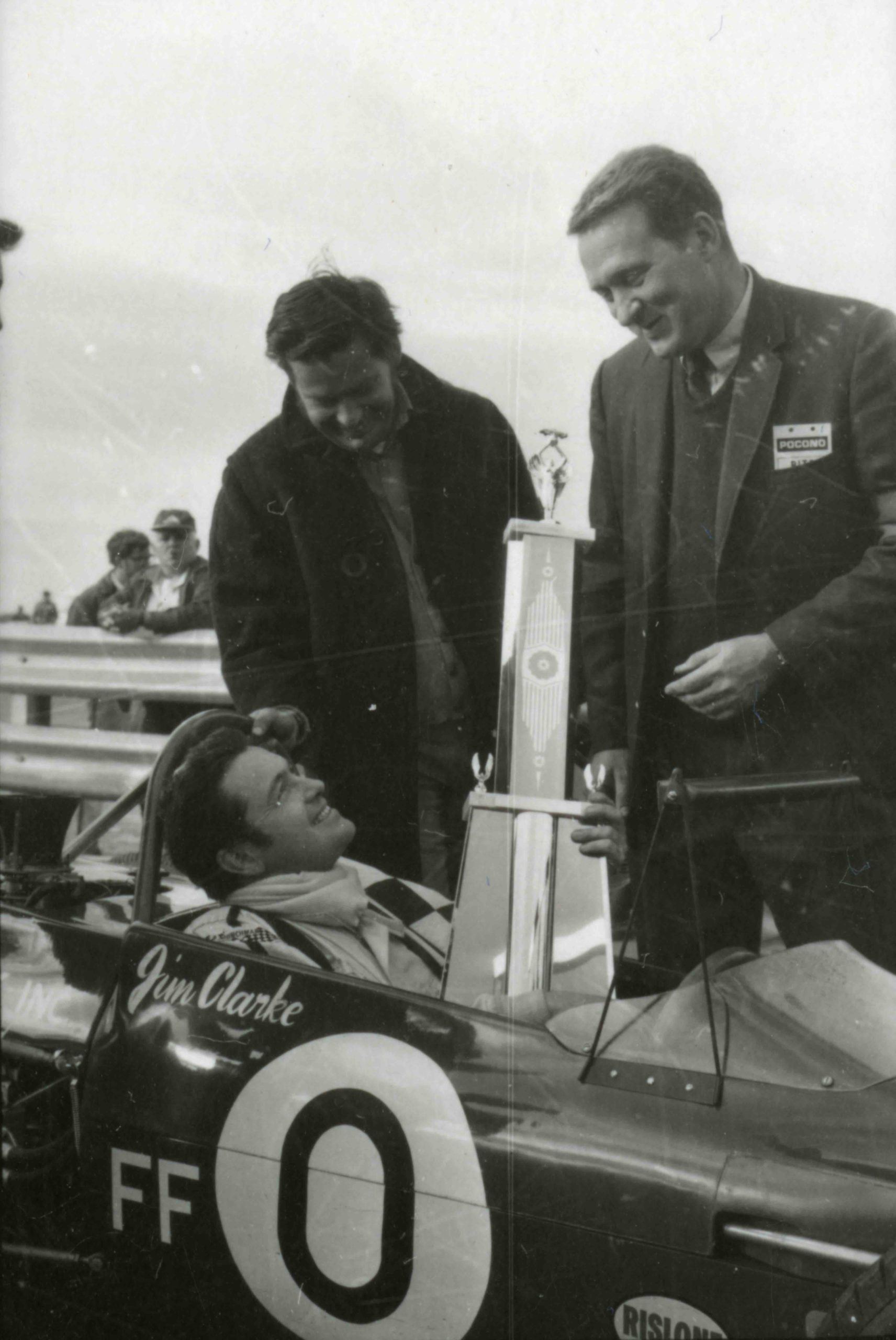

Winner Jim Clarke receives congratulations from the IMSA founder following the first race at Pocono. It wasn’t until after the trophies and prize money were handed out that a scoring error was discovered. It was never corrected. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research

At the end of the race, Jim Clarke was declared the winner, and a modest Victory Lane ceremony was held. Post-race analysis, however, revealed that an error had been made and the second-place driver, Jim Jenkins, had actually won. But the ceremonies were over, the spectators were long gone and teams were packing up to go home. Bishop decided to let the results stand. They were never corrected.

“Don and Ruth Nixon were running timing and scoring for us that race,” Bishop recalled. “The rest of the scoring team was largely made up of drivers’ wives. When Carson Baird crashed on lap 31, his wife Betsy stood up and screamed. Peggy told her to sit down and keep scoring. Somehow, we missed the real winner. Jim Jenkins should have won the race but instead, the win was given to Jim Clarke. I remember Don Nixon running down the grandstand shouting, “Don’t give out the checks!” but by then it was too late.”

After all the drama and hard work, IMSA had pulled off its first race. Yes, the crowd was small and there were issues, but the sanctioning body was now off and running.

Just two months later, IMSA held three races at the newly built Alabama International International Speedway (Talladega), one each for Formula Vees and Formula Fords, and one for a new class called International Sedans. For the first time, they used the four-mile combination oval/road course, even though Bishop was beginning to get concerned about the safety of running open-wheel formula cars on ovals. “Race cars have to be faster than the track,” he pointed out. “If the track is faster than the cars, then you have the potential for big trouble. We learned that the hard way with Formula Fords at Charlotte the next year.” Race day was not a commercial success; the 500 spectators were completely lost in the grandstands designed to hold thousands of rabid NASCAR fans.

The 1970 season was largely focused on running more formula car races on a mixture of ovals and road courses, starting with season-opening events at Daytona in February during Speed Weeks. The Formula Vee race had just twenty entries but paid the winner Bill Scott more than $5,000, a princely sum at the time. A week later, IMSA put just 15 Formula Fords on the grid at Daytona. Both races were run on the combined oval and infield road course.

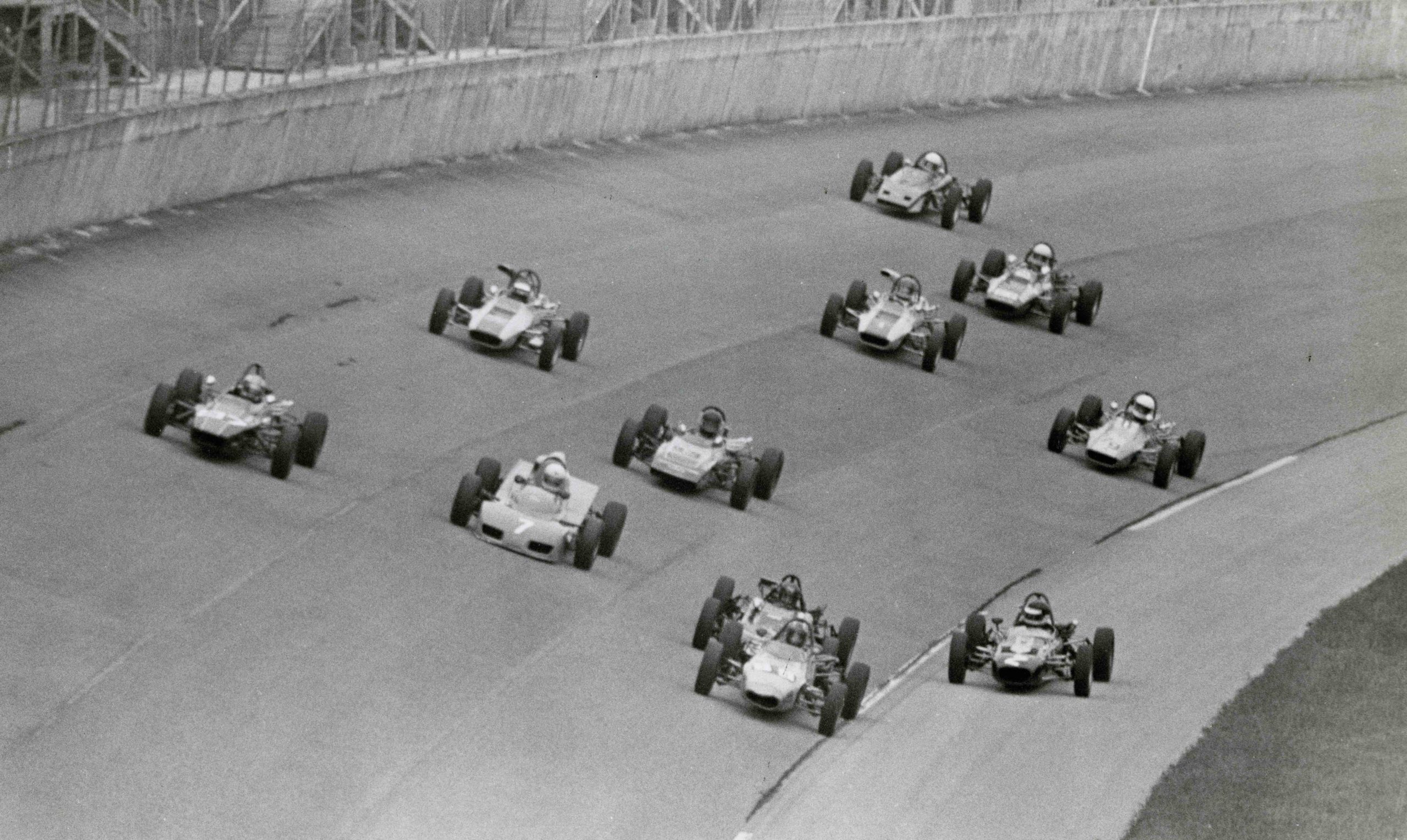

Putting a bunch of Formula Fords on the wide-open expanses of Alabama International Speedway (Talladega) was a recipe for exciting pack racing but also an invitation to disaster. Photo: Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research

Thirty-Three Formula Fords showed up for the next race in April at Talladega. Again, the drafting and dicing on the oval section was spectacular, but with more cars on the track the inevitable happened; there were multi-car wrecks in the first heat that damaged 13 cars badly enough they were unable to start the second heat. Fortunately, no one was seriously hurt but John Bishop was shaken by the close calls. IMSA was barely limping along; somehow IMSA had dodged a bullet.

Early laps of the Formula Ford race held on the full oval at Charlotte Motor Speedway in May 1970. Gary Weber in No. 00 leads Vic Matthews in No. 1 prior to a dangerous wreck. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

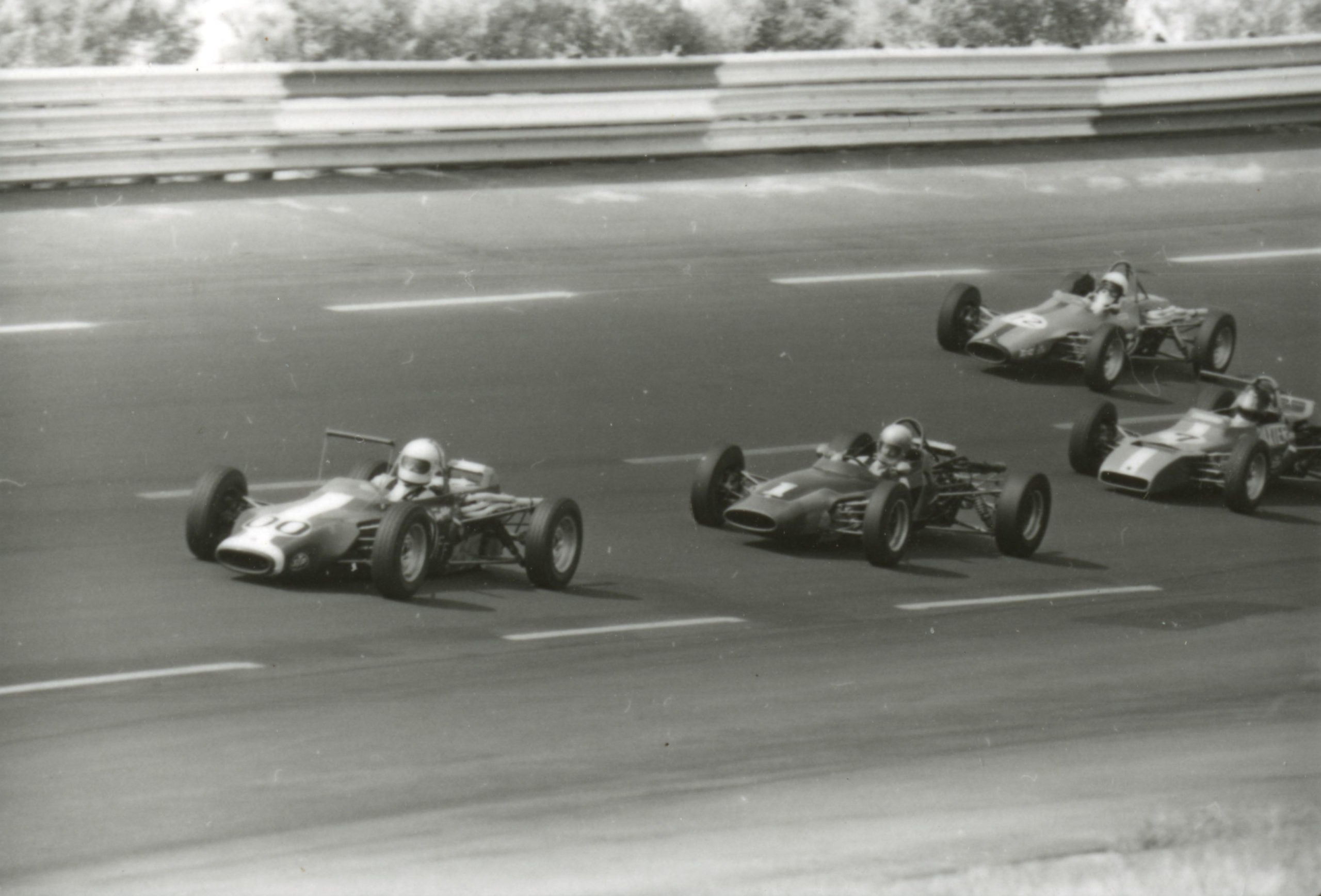

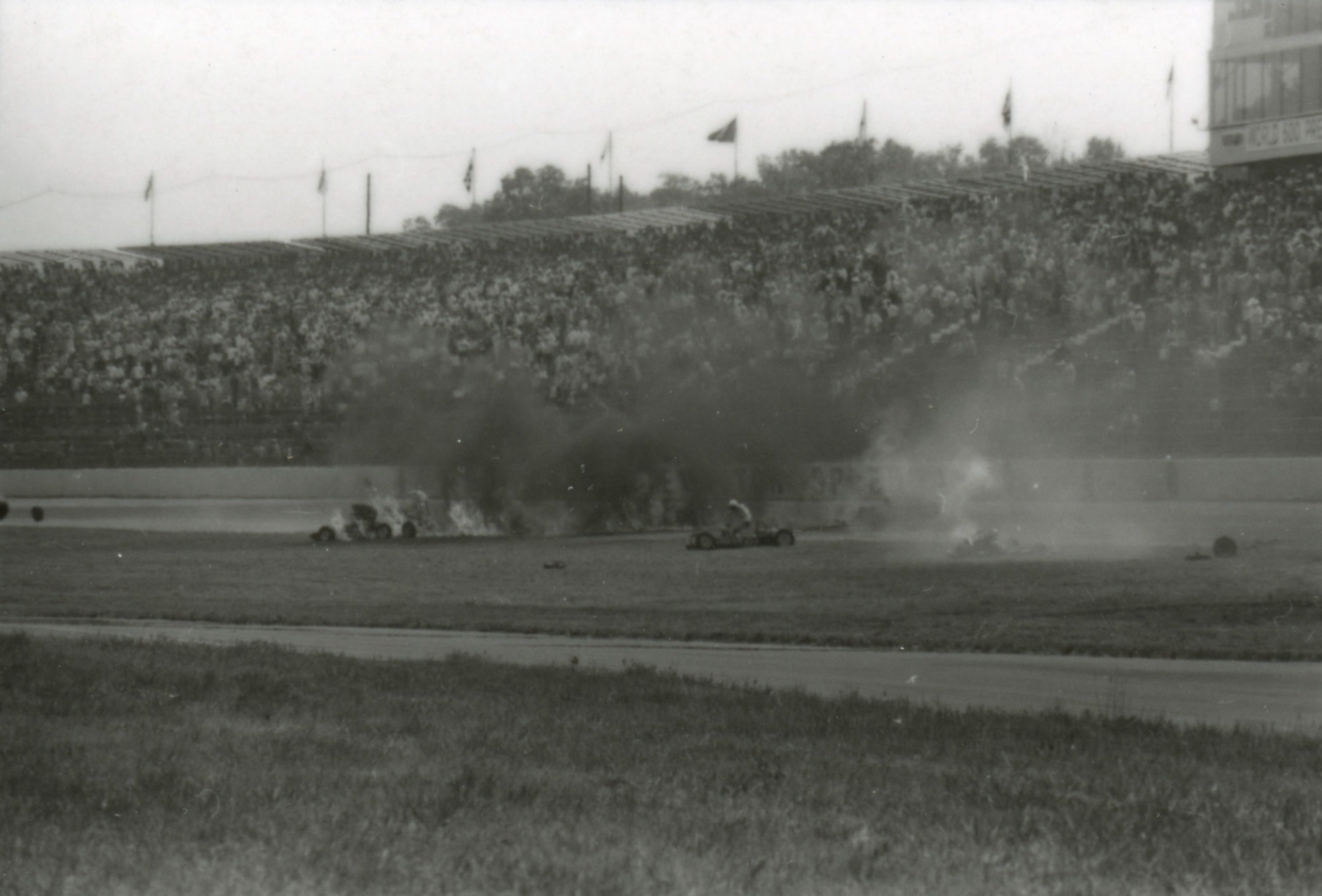

The race at Charlotte Motor Speedway in May was the turning point. Run on the full 1.5-mile oval, the field of 22 Formula Fords ran in a tight pack the entire first heat, drivers drafting each other within inches of one another. No one could break away from the bunch. Passing required staying in the draft, tight on the tail of the car in front, gaining momentum and then dodging right or left out of the slipstream. Entering the front straight, the leading pack of six cars came together in a spectacular crash. After touching wheels, Vic Matthew’s Macon flipped end-over-end, as did the car of John Kinney. Bob Gardner ended up in the wall. The declared winner of the first race at Pocono, Jim Clarke, ended up underneath Spurgeon May’s Caldwell, effectively trapping Clarke in the car. After coming to a halt on the grass, the stack of two cars burst into flames. Spurgeon climbed out but Clarke was wedged in his car, unable to exit.

A very rare sequence of shots of the huge wreck at the IMSA Formula Ford race at Charlotte in May 1970. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

Spurgeon May pushes his car out of the way after the Charlotte crash. His Caldwell Formula Ford came to rest on top of Jim Clarke’s machine before both cars were engulfed by flames. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

As Clarke later recalled; “After the initial impact, when we came to a stop, I remember thinking that I was lucky to be unhurt. Then, I smelled gasoline and thought to myself: I need to get out of here! After we caught fire, my next thought was: well, this is it, there’s no way out, I’m going to die. I resigned myself to my fate. Then it started to get really hot and I thought: The heck with this, I’m getting out of here! And I did something no one thought possible; I punched a hole in the side of the fiberglass bodywork with my fist and crawled out.”

The race was red-flagged and never restarted. Kinney and Matthews were both hospitalized with head, ankle, and burn injuries. A total of eight cars were damaged beyond repair in time for the second heat run later that day, which was shortened due to safety concerns. No one was killed in the melee and the injured recovered. But once again, IMSA had just barely dodged a bullet.

IMSA was struggling. Beyond the safety issues, not enough people were coming out to see the races. The company was in the red and had to borrow more money to stay afloat. It was time for a new vision. Bishop wrote an entirely new rule book in the fall of 1970 for the following season with the help of Charlie Rainville and input from some of the key drivers of the day like John Greenwood and Peter Gregg. That winter, the rule book was widely distributed to SCCA racers who had already built FIA Group 2 and Group 4 cars but didn’t have a place to race them professionally other than the annual endurance events at Daytona, Sebring and Watkins Glen. Reaction was positive, both from competitors and track promoters. Jim Haynes at Lime Rock and Les Griebling at Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course both signed on right away, as did the folks at Bridgehampton Race Circuit.

The new IMSA GT series debuted in April 1971 at Virgina International Raceway. It was an instant success with promoters, drivers, team owners and sponsors. Camel cigarettes joined as the series sponsor at the end of 1971 and starting in 1972, the Camel GT Series quickly became the most popular professional sports car racing series in the world.

The following is an excerpt from the book, IMSA: 1969-1989, by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Porsche’s dominance during the 1974 season began to weigh on John Bishop. He understood the Camel GT Series was not sustainable if it became a one-marque show. And he worried about escalating costs if European manufacturers like Porsche and BMW controlled the supply of the most competitive cars. He wanted to find a way to bring American manufacturers to the front of the grid and offer a cost-effective, competitive product to private teams. But how? The answer came to him on an airplane.

“The old system favored limited production cars like Porsches and BMWs,” John later recounted. “There was no way high volume, cheaper production cars could compete with limited production cars with better components. They were simply better cars. What we needed was an American car that could compete with limited production sports cars from Europe. In the middle of the 1974 season, I was on my way somewhere on an airplane. It occurred to me that Porsche was abusing the FIA Group 5 rules with the turbo-powered 934 and then the 935 with its wilder bodywork. The Group 2 and 4 rules limited what you could do with the bodywork but not so with the Group 5 rules. There was total disregard for the future of the class. We couldn’t ban the Porsches. So, I figured we’ll just do what they’re doing.”

John Bishop’s original sketch of the All American GT concept he made on an airplane in 1974. This first concept drawing turned out to be very close to the first machines built for the AAGT class. Photo credit: Bishop Family

John Bishop’s original sketch of the All American GT concept he made on an airplane in 1974. This first concept drawing turned out to be very close to the first machines built for the AAGT class. Photo credit: Bishop Family

On the airplane, Bishop quickly sketched out his vision for American-based, tube-frame cars powered by readily available, low maintenance V8 engines, a class of cars that would be able to compete with the limited production, high-cost European Porsches and BMWs. He decided to call it All American GT (AAGT).

“The AAGT class was designed to allow tube-frame American cars to compete with limited production sports cars from Europe,” John recalled. “Porsche 935s were tube-frame cars at the end of the day. The only difference was that they rolled off a special production line in Germany, ready to race. The name AAGT came from our desire to give other people the same advantages that, by stretching the Group 5 rules, Porsche had enjoyed.”

Bishop started to share the AAGT concept in 1974 with some of the top competitors and at the end of the year IMSA published AAGT rules for the 1975 season. Steve Coleman and Amos Johnson debuted the very first AAGT car, a Chevy Vega they had built themselves, at the 1974 Daytona finale, where the car retired after managing just seven laps.

Steve Coleman and Amos Johnson’s home-built Chevrolet Vega, entered at the Daytona finale in November 1974, was the first AAGT in IMSA. Photo credit: ISC Archives & Research Center/Getty Image

“That was one of the overriding happiest reflections on IMSA,” remembered John later. “We could write a set of rules, talk about them with competitors, team owners and the like, publish the rules and then everybody would say; “Yes sir!” And they would go out there and spend money to build a car to those rules. We could create something great from just an idea.”

The new AAGT concept grabbed the attention of car builder and top engineer Lee Dykstra, who entered into a partnership with Horst Kwech in 1974 to form DeKon Engineering with the express purpose of designing, building and selling a competitive AAGT racer. With the direct assistance of Chevrolet, they began taking delivery of engines and other parts to construct the first wave of tube-frame Monzas. At just 2,400 pounds and powered by small-block V8s initially using Weber carburetors and later direct fuel injection, they produced 600 to 650bhp, making the Monzas balanced and lightning-fast. Purpose-built for racing, the only production parts appeared to be the roof and the windshield.

Kwech, already an accomplished racer, debuted the first production DeKon Monza at the Road Atlanta Camel GT doubleheader in April of 1975. He qualified fifth out of 40 cars entered, which got everyone’s attention, but retired after just 13 laps in the opening heat and didn’t start the second heat the next day due to teething issues. The bright spot was a privately built AAGT Monza driven by Tom Nehl, who finished eighth in both heats. The rest of the paddock began to see the potential of the new cars.

The first DeKon Monza campaigned in two races during the 1975 season. Australian Allan Moffat drove it at the Daytona 250-mile finale, on his way to a DNF after completing just fifteen laps. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com

DeKon Engineering continued to develop the car while another, privately-built version of the Monza arrived in the hands of Warren Agor, who finished a respectable 12th and 10th in the two heats at Lime Rock and scored another 10th at Mosport.

It was just a hint of things to come.

The AAGT concept gained speed with Porsche’s focus on the 934 and the Trans-Am for 1976. It put the top IMSA Porsche teams in a bind. Could they be competitive with the now-aging Carrera RSR against the BMW CSLs and new AAGT Monzas?

Al Holbert decided the answer was no. Although he had lobbied for the inclusion of the Porsche 934 for 1976, he preferred the larger rear wing, wider rear tires and lighter weight of the Monza compared to the RSR. Holbert purchased a DeKon Monza for the 1976 season and ran his first race at Road Atlanta in April with it after wisely sticking with the more reliable Porsche RSR for the longer Daytona and Sebring rounds. He finished second at the 24 hours of Daytona and won Sebring in March, co-driving with Michael Keyser, who then switched to the Monza.

By the Road Atlanta round in April, eight small block Monzas showed up from three constructors, including examples fielded by Keyser, Agor, Trueman, Nehl, Tom Frank and Jerry Jolly. There were many other AAGT cars as well: Coleman’s original AAGT Vega, five Greenwood- style Corvettes, Charlie Kemp’s wild Cobra II built by Bob Riley, and a host of Camaros led by the big orange No. 21 of Carl Shafer. Holbert and Keyser finished first and second in their DeKon Monzas, humiliating the rest of the field. The AAGT era had officially come of age.

Charlie Kemp’s wild AAGT Cobra II blowing smoke out the exhaust headers at Daytona. IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

Holbert went on to win four more races in the Monza to take the 1976 Camel GT championship. Keyser won two races with his version as well, cementing the future of American-built, tube-frame racers as the equal of anything produced on assembly lines in Europe. The Porsche Carrera RSR contingent included the usual faces along with George Dyer, Roberto Quintanilla, Bob Hagestad, John Gunn, John Graves, Monte Shelton, and others.

A host of Monzas head into the final turn at Laguna Seca during a heat race in 1977. Tom Frank leads Michael Keyser, Greg Pickett, Chris Cord, and Brad Frisselle, who took delivery of his car right before the race from Keyser and didn’t have time to apply graphics. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com

Al Holbert won a second consecutive Camel GT championship in 1977 in his potent AAGT Monza, updated with a larger rear wing, wider wheels, and more generous bodywork modifications that were allowed under new GTX rules. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com)

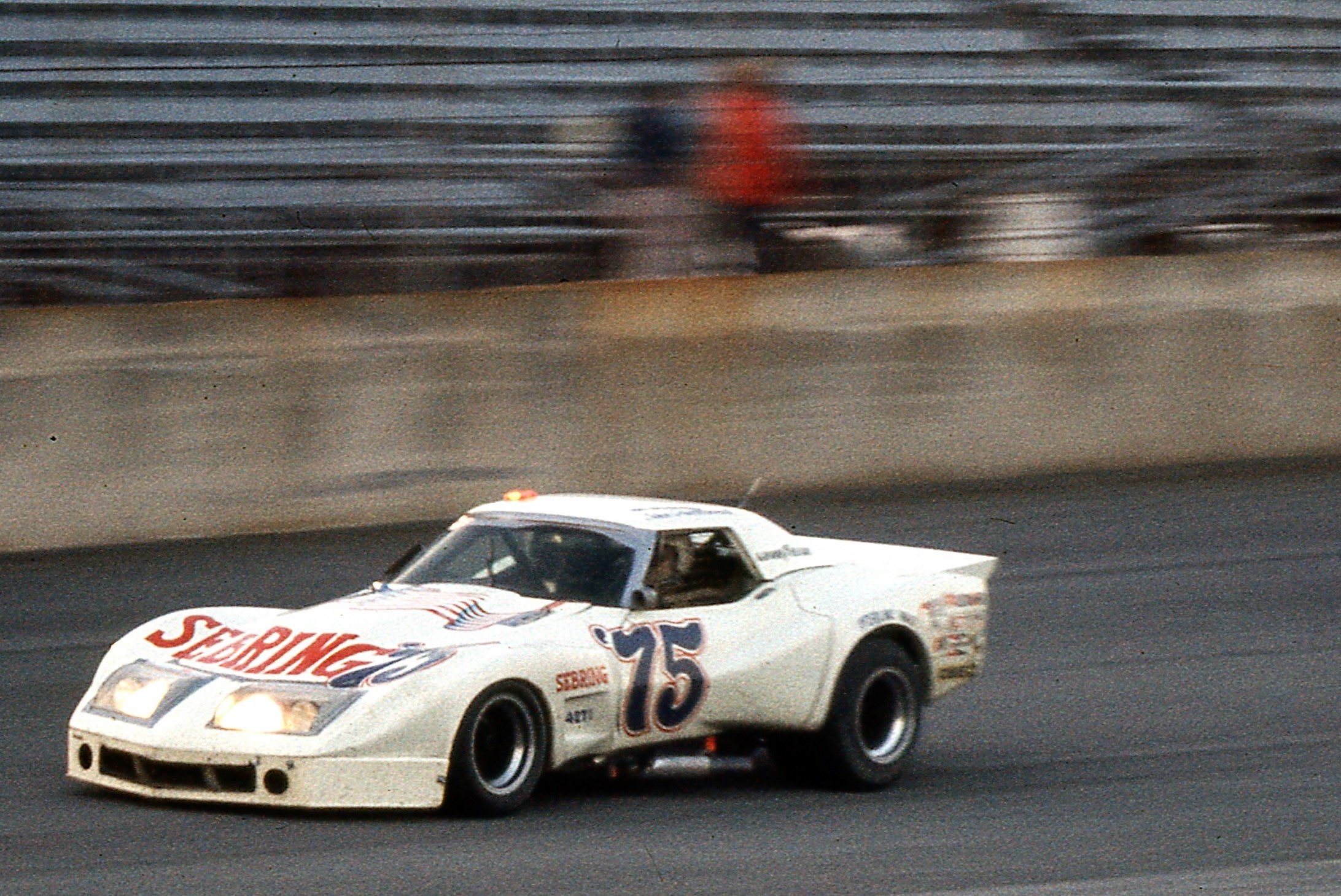

The AAGT revolution continued unabated for several years. Holbert won a second championship in a new winged Monza in 1977 against an onslaught of Porsche 934/5s. Other manufacturers became involved in the AAGT class, including Bob Sharp with the Datsun 280ZX twin-turbo V8. The bodywork, aero packages, and engines got so outrageous that IMSA dropped the AAGT moniker and changed the name of the class to GT eXperimental (GTX) in 1978. GTX became a combined class that included Group 5 Porsche 935s and all manner of AAGT machinery.

With rules changes that allowed for wilder bodywork, AAGT machinery continued to compete effectively with the Porsche 935 and the BMW turbo in 1978. Carl Shafer’s Camaro exits from under the bridge at Road Atlanta and starts the downhill plunge to the start/finish line. Photo credit: Bruce Czaja

The following contains excerpts from “IMSA 1969-1989” written by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf, and published by Octane Press, which tells the inside story of how IMSA got started and its first 20 glorious years. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

When IMSA started sanctioning GT races in 1971, the big prizes on the horizon for the organization were always the 12 Hours of Sebring and the 24 Hours of Daytona. Both events had achieved international fame by then, attracting the best and brightest drivers from Formula One, world endurance racing, USAC, and the SCCA. But for different reasons, both events were in trouble by 1973. The FIA had dictated track and safety improvements at Sebring, which led the Ulmann family to announce that the 1972 race would be the last. IMSA picked up the pieces in 1973 thanks to the backing of John Greenwood, the organizational efforts of Reggie Smith and the work of IMSA founder and president, John Bishop.

In the meantime, ever-changing FIA technical rules for world endurance racing were limiting interest and even the length of the Daytona event, which ran as a six-hour event in 1972 due to concerns that the fast prototypes from Ferrari and Alfa Romeo wouldn’t last a full 24 hours. Other manufacturers like Porsche had long decided to pull out of the event.

Once IMSA joined ACCUS in 1973, it successfully lobbied to take over organizing the 24 Hours of Daytona starting in 1974. Unfortunately, in October that year, Saudi Arabia- controlled OPEC organized an oil embargo in retaliation for United States support of Israel during the Yom Kippur war. Over the next few months, the price of oil spiked globally and long lines formed at the pumps as shortages spread. Things got so bad that a rationing system based on the last digit of license plate numbers dictated which days people could purchase gasoline.

The shortage quickly put pressure on motorsports, which some saw as the wasteful use of a now precious commodity. Recently promoted NASCAR President Bill France Jr. organized an effective lobbying campaign in Washington D.C. to keep Congress from legislating NASCAR and other sanctioning bodies out of business. He pointed out the reality that it took less energy to put on a race than to fly an NFL football team coast-to-coast. The strategy worked, but concessions had to be made during the embargo, which lasted until April of 1974. Some races were shortened such as the Daytona 500, which ran only 450 miles.

IMSA’s two major endurance races were canceled outright in 1974. Even though IMSA had become a full member of ACCUS and had won the right to sanction the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1974, the race was shut down due to the shortage; Daytona’s owners could not guarantee a supply of fuel to support the thousands of fans expected to attend the event. Sebring was canceled for similar reasons, making the Road Atlanta round the opening race of the 1974 Camel GT season. The event was stretched to 6 hours in homage to Daytona and Sebring and was won by Al Holbert and Elliott Forbes-Robinson in a 3.0 liter Porsche Carrera RSR.

George Dyer’s Porsche Carrera RSR at Daytona in 1975 at sunrise on Sunday. Yes, there used to be trees visible in the infield section of the road course. Photo: MarkRaffauf

Thus, the 24 Hours of Daytona became the opening round of the Camel GT Series in 1975 and marked the first time that IMSA sanctioned the event. A healthy field of 51 over- and under-2.5 liter GT cars started the race on Saturday, February, 1st. There were no prototypes running in IMSA at that time. Although the first All-American GT cars were beginning to be built, none showed for the twice-around-the-clock endurance event. Horst Kwech would debut the first production AAGT DeKon Monza later that year at Road Atlanta.

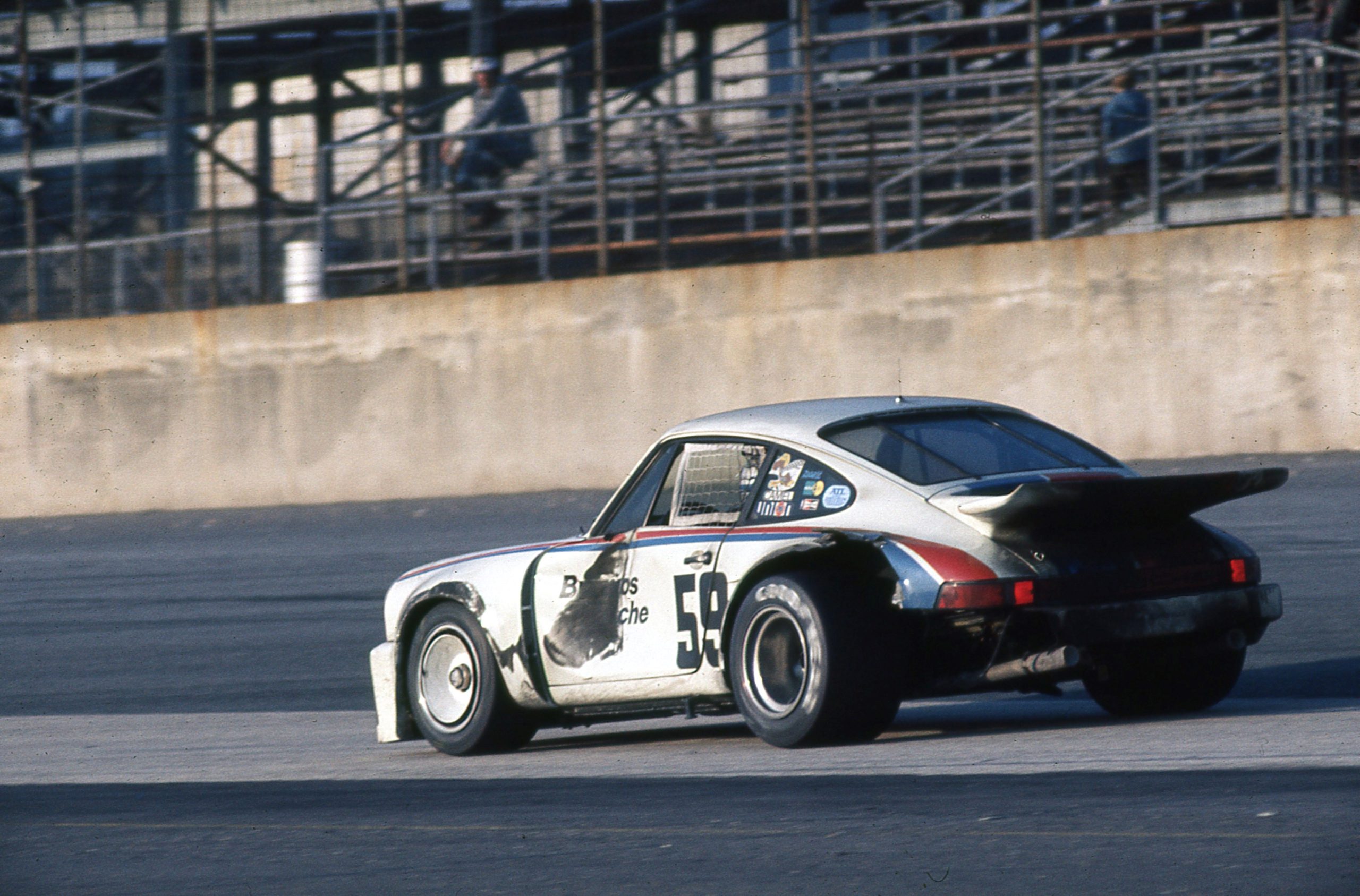

The winning Brumos Porsche Carrera RSR enters Turn One during the 24 Hours of Daytona in January 1975. Note the crash damage caused by an incident earlier in the race with Hector Rebaque that required a lengthy pit stop to repair. Photo: MarkRaffauf

Twenty-one of the entries were Porsches. By then, Porsche had been building a very successful customer car program under the direction of Jo Hoppen, the head of Porsche Motorsports USA. Hoppen aggressively drove a customer car program that became the de facto model for other manufacturers in the sport. When the International Race of Champions switched from Porsche to Camaros for the 1974 season, 15 Carrera RSRs instantly became available for IMSA racing. They had rolled off the production line at a German factory ready to race; anyone with the right-sized checkbook could buy one. The cars were sorted, reliable and fast. Hoppen placed the cars with good teams, which filled up IMSA fields for the next few years with strong entries carrying the Porsche banner. He also arranged for a fully stocked Porsche parts trailer to show up at every IMSA event, ensuring that all the teams were well supported.

John Greenwood’s Corvette was one of the Porsche antagonists. Seen here under braking for Turn One during the 1975 24 Hours of Daytona, it featured a paint scheme promoting the 12 Hours of Sebring a few weeks later. Greenwood’s big-block Corvettes with wild bodywork were fast (he won the pole for the race) but didn’t last the distance, completing just 148 laps. Photo: MarkRaffauf

In other news, one of the newcomers to IMSA at Daytona in 1975 was the first factory “super team” from Europe. Jochen Neerpasch brought the latest factory BMW CSL team to the premier IMSA series with pilots Brian Redman, Hans Stuck, Ronnie Peterson, Dieter Quester, and Sam Posey. As the U.S. market recovered from the gas crisis, BMW wanted to use racing to underscore its core marketing message: “The Ultimate Driving Machine.” The addition of BMW and top European drivers to the series also had the effect of raising the competition level significantly. A proven entity in Europe, the CSL had struggled in the U.S. in 1974 without proper factory backing.

Unfortunately, neither car finished the 1975 24 hour race, with the Redman, Petersen car dropping out after just 29 laps and the Stuck, Posey car ending up in 33rd spot. After the disappointing results against an army of Porsche Carreras, the BMW team regrouped and moved its U.S. operations deep into NASCAR country: the shops of Bobby and Donnie Allison in Hueytown Alabama. The team spent a month modifying the standard European-version of the CSL into a potent IMSA contender by removing weight, stiffening the chassis, improving engine reliability and tweaking aerodynamics. The changes worked; BMW won the 12 Hours of Sebring in March and became a contender throughout the rest of the 1975 season.

The winning factory BMW CSL of Hans Stuck, Sam Posey, Brian Redman, and Allan Moffat navigates the wide-open runways of Sebring in 1975 when Lockheed Constellations and Douglas DC-4s lined the course unprotected between Turns One and Two. Photo: Mark Raffauf

Against this backdrop, the 1975 Daytona 24 Hours was an all-Porsche affair. The only drama was: which Porsche would win. Peter Gregg tangled early on with the RSR that had won the Mexican round of the FIA’s World Championship of Makes the previous year. The No. 5 Café Mexico Porsche was driven at Daytona by Hector Rebaque, Fred van Beuren, and Guillermo Rojas. After the incident, both cars spent many laps in the pits to repair damage and fell back in the standings.

Peter Gregg leads the similar machine of Rebaque/Rojas/van Beuren during the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1975 on Sunday morning. The two cars came together early in the race, requiring extensive repairs to both. Hurley Haywood and “Peter Perfect” came back to win with a car that was not so perfect. Photo: MarkRaffauf

Throughout the evening the Brumos car gained ground back with Gregg and Hurley Haywood alternating behind the wheel. A thick fog rolled in as the night progressed and visibility became a real issue. Haywood got into the car just past midnight for what was expected to be a three-hour stint since Gregg was never a big fan of driving at night or in lousy weather. Haywood, who had extraordinary vision, always seemed to get the nod in those conditions.

Despite the fog, Hurley kept circulating at close to qualifying speeds through the night. He drove longer than expected and probably longer than technically allowed. In the process, he dragged the battered No. 59 back onto the lead lap and eventually into the lead, the entire time his car barely visible to race control.

When asked his status by IMSA officials over the radio, he continued to report, “I can see everything fine down here on the ground,” which may or may not have been entirely true. Haywood drove an epic six hours straight, taking the lead and ultimately winning the race for the Brumos team. It would be one of five victories for each of the hall of fame drivers at the storied 24-hour event. In the end, Porsches occupied 13 of the top 15 spots in the results.

As the founder of NASCAR, Bill France, Sr. was a force to be reckoned with. Physically intimidating but soft-spoken, “Big Bill” guided the growth of stock car racing with an iron hand into a powerful and popular regional sport in the 1960s. But many people don’t realize that Bill Sr. was also keen on establishing Daytona International Speedway, which he built in 1958, as a center for international motorsport.

In June of 1961, “Big Bill” and his son Bill France Jr. attended the Le Mans 24 Hour race as guests of the organizers. The sights and sounds of the cars were enticing but most intriguing were the more than 150,000 spectators filling the grounds of the track. This gave France Sr. an idea: could Daytona hold a similar style event and fill the stands? He reached out to his friend John Bishop, who was about to become the executive director at the SCCA, to help put the idea into action. As Bishop remembered: “When the SCCA went pro racing in 1961, there was an ACCUS meeting in New York City at the Drake Hotel. Bill Sr. invited me up for breakfast before the meeting and asked me: ‘Would you be interested in a new event? We’d like to get involved with the SCCA in putting on a major race in the early part of the year and we’ll call it the Daytona Continental.”

In the ensuing months, Bishop, and the two Frances had several meetings to plan what would become of the Daytona Continental that soon morphed into the 24 Hours of Daytona. The timing could not have been more perfect; the Club was just putting its professional road racing blueprint into motion and sanctioning the Daytona event would give it a much-needed leg up in that direction. Bill Jr. advocated for a 24-hour race from the start, but his father understood the need to ease into a longer event to avoid any political fallout with the Automobile Club de l’Ouest, the organizers of Le Mans.

The 1962 Daytona Continental three-hour race for sports and grand touring cars was held in February and fully sanctioned by the SCCA. Internationally famous drivers like Phil Hill, Jim Clark and Sterling Moss competed directly with top U.S. talent represented by A.J. Foyt, Dan Gurney, Walt Hansgen, Roger Penske and Briggs Cunningham. The race was won by Gurney, who coasted his Lotus-Climax over the finish line using only his starter motor since his engine had blown three minutes from the end of the race. In spite of a media tour held in New York the month before, attendance was light.

Fortunately, sports car racing (and Bishop) had an advocate in France Sr. He understood that it was going to take time to build an audience for this new spectacle and his vision of international recognition for Daytona intertwined with sports cars. This friendship culminated in France, Sr. coming up with the idea to start IMSA in 1969 and providing the funding to start the organization. Early IMSA races consisted of Formula cars (Fords, Vees, Super Vees) on ovals. But scary crashes and injuries in 1970 led IMSA to pivot towards sanctioning sports car races for FIA Group 2 and 4 GT cars. Aside from the 24 Hours of Daytona and the Watkins Glen 6 Hour, these cars had nowhere else to race for prize money during the season. It turned out to be the start of something big that eventually grew into the Camel GT Series starting in 1972.

One of the earliest experiments with this category happened in November of 1970 at Alabama International Motor Speedway (now called Talladega). In a show of support, both Bill Sr. and Bill Jr. entered the race in matching Ford Cortinas that had been bought used from a local dealer and outfitted for racing. The ragtag field of cobbled-together machines included the founder and president of NASCAR and his son! Ultimately the son bested the father by finishing 9th in the race, while his father finished 17th. Here are some rare photos from the event.

Bill France, Jr. (left) talks with his father, NASCAR founder Bill France, Sr., before the IMSA sedan race at Alabama International Motor Speedway in November 1970. Note that Bill Sr. is wearing a dress shirt and tie under his driving overalls! Photo: IMSA collection at the International Motor Racing Research Center

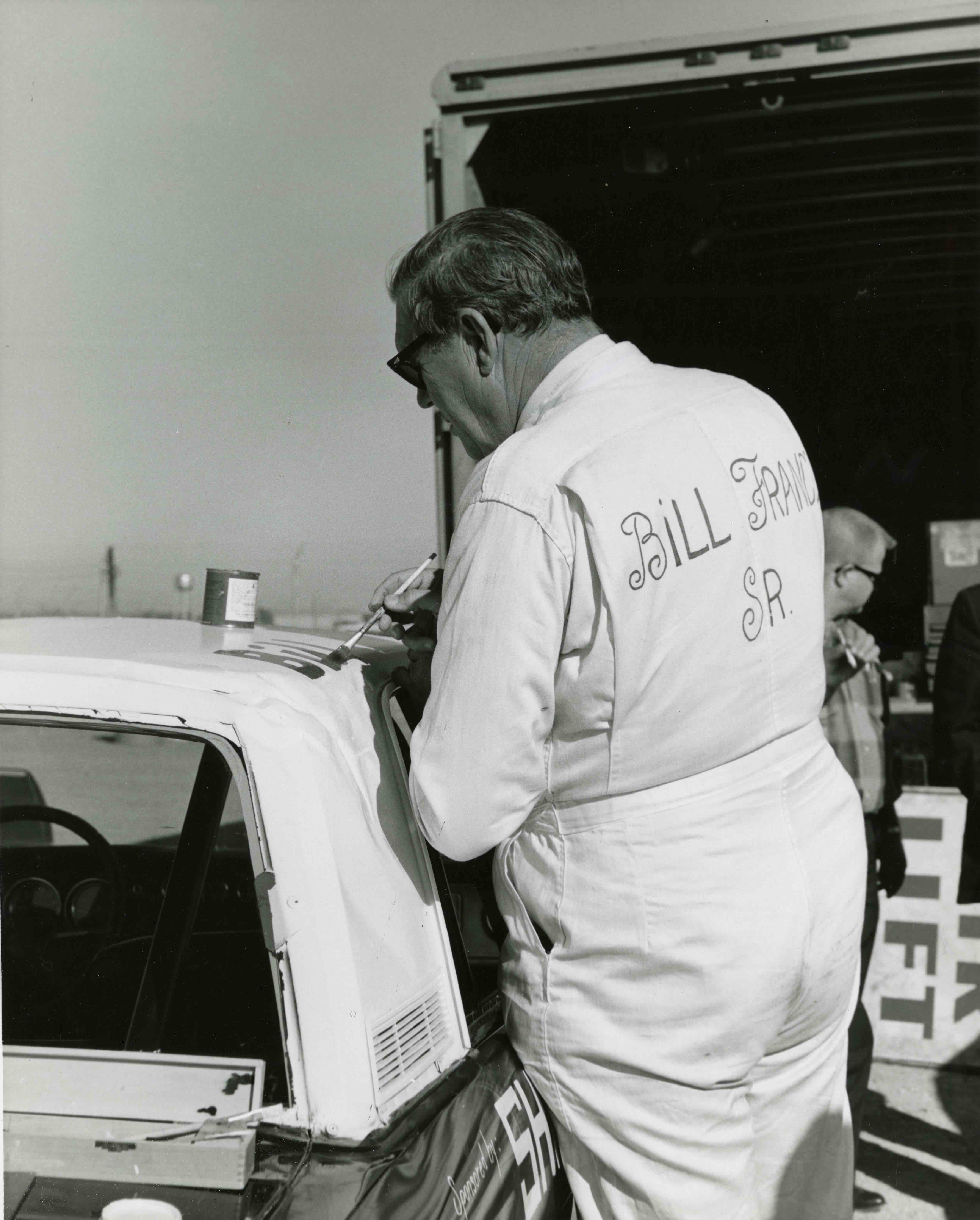

It was apparently a do-it-yourself kind of weekend. Bill France, Sr. paints his name on the top of the Ford Cortina he’s about to race in the IMSA event at the relatively new Talladega superspeedway in November 1970. Photo: IMSA collection at the International Motor Racing Research Center

Bill France Sr. leads Bill France Jr. in their Ford Cortinas at Talladega in November 1970. The younger France would finish 9th, ahead of his father, who finished 17th. Photo: IMSA collection at the International Motor Racing Research Center

Bill France, Sr. comes in for a pit stop during practice for the race. Photo: IMSA collection at the International Motor Racing Research Center

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” written by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf that tells the inside story of how IMSA got started and its first 20 glorious years. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Standing at just 5 feet, 6 inches tall, Charlie Rainville’s small stature didn’t seem at first glance to be a good fit in the high stakes, high-pressure world of big-time sports car racing. But competitors and manufacturers that underestimated him quickly learned the hard way that Charlie was not a man to be trifled with. He was tough as nails, a kid that grew up on the wrong side of the tracks in Providence, Rhode Island. He was street smart, savvy and ready for a fight. But he was also immensely clear thinking and eminently practical when it came to managing the many conflicting personalities that were each vying for an unfair advantage. The ever-present twinkle in his blue eyes and ready smile were Rainville’s main weapons for disarming tense situations, but he also commanded immense respect from competitors familiar with his experience.

One of the original pioneers of U.S. road racing, Charlie had earned a reputation as a tough competitor and brilliant race car preparer, starting as a mechanic at Jake Kaplan’s Import Motors shops in Providence in the late 1950s. Known for being able to massage anything to go faster than originally intended, he was the go-to guy for preparing sports cars in New England for the growing groups of enthusiasts importing them from Europe. Charlie became an expert on all of the exotic cars of the day, including Alfa Romeo, Jaguar, Lotus, Ferrari, Porsche, OSCA, Iso Grifo, Datsun, and Corvette. In addition to engines and suspension setup, he became a true artist, hand forming aluminum body panels for all sorts of makes and models.

An accomplished racer, Charlie Rainville drove for the factory Plymouth Trans-Am team in 1966, including the opening round at Sebring, where the Trans-Am cars had a four-hour race ahead of the 12 Hour classic. Photo: REVS Institute

As a driver, Rainville had a brief career in sprint cars and on short tracks until he gravitated to SCCA track events, hill climbs and rallying in the New England area, campaigning in aluminum- bodied XK120 Jaguars, Alfas, OSCAs, and Cobras. He then jumped to the professional ranks by competing in SCCA Trans-Am series events in Barracudas as part of the first works team from Detroit in 1966. A few podiums and a fifth-place overall finish in the points that first year of the Trans-Am would mark the pinnacle of his driving career. Along the way, Charlie built a reputation for helping anyone in the paddock with parts, labor, and advice, and then going out and beating them on the track.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR: Don’t Lean Too Hard on the Doors

The cars for the first-ever Trans-Am race were run as a separate class at the Sebring 12 Hour in 1966. As both John Bishop and Charlie Rainville relayed it, they met on the grid just before the race. John went over to the driver’s side of Charlie’s car to wish him good luck in the race. As he leaned in on the door to talk, the door started collapsing. John knew that the SCCA had approved alternative thin steel door panels for the Plymouth, but he was unprepared for how thin! Charlie laughed and promptly pounded the panel back out with his fists from inside the car and made no reference to the fact the door was, in fact, aluminum which, needless to say, was not a standard Barracuda part in 1966. John gave his apologies for damaging the car, along with a wry smile and walked away. Charlie went on to finish seventh that day.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By the end of the 1960s, Rainville had retired from racing and evolved into one of the top SCCA race stewards in the country. He and Bishop had crossed paths many times by this point. Bishop saw that Rainville’s view of how racing should be conducted matched his own and when the opportunity came to forge a partnership of philosophies, he became the obvious choice to lead the charge for IMSA at the track when it came to technical and competition matters.

The man who made the tagline “Racing with a Difference” come to life at IMSA events for many of the participants was Rainville. He was IMSA’s chief steward, race director, technical director and director of competition from IMSA’s start through the early 1980s. In appointing him to these positions, Bishop understood that Rainville brought decades of useful experience in car construction, race preparation, competition driving and race officiating to the table. He knew instinctively that Charlie would command immediate respect from competitors, team owners, race organizers and manufacturers.

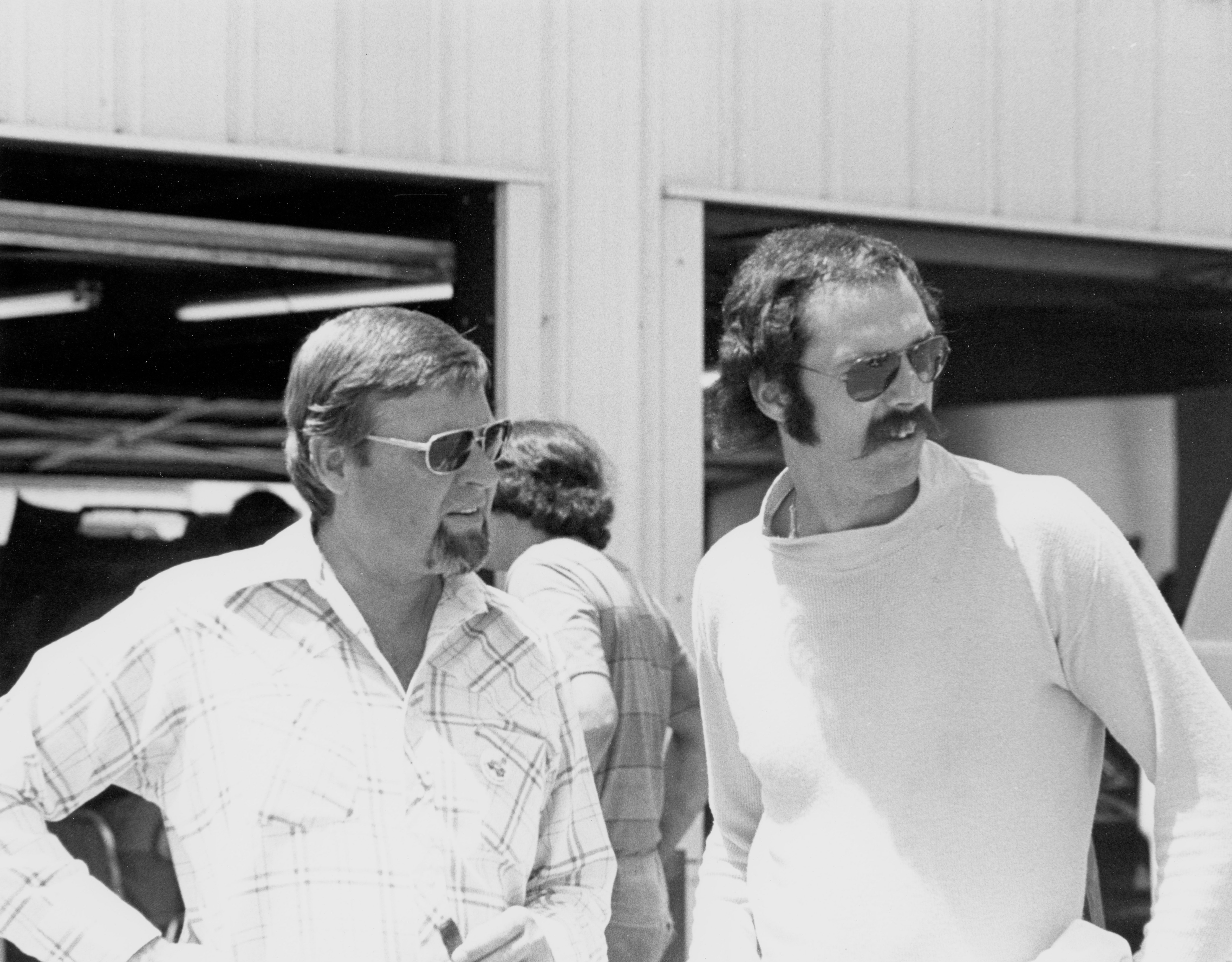

The solid partnership forged between Charlie Rainville and John Bishop made IMSA tick for many years. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

Rainville’s no-nonsense, common sense approach to technical rules, race regulations and race management confirmed he was the logical choice to run the competition side of the new organization. He introduced a new style of series management: benevolent dictatorship, something competitors had not experienced in the highly political world of the SCCA.

Hurley Haywood had this to say about Rainville: “He would look at the situation and say, “That’s a good idea,” or “No, that’s not a good idea.” There was no discussion. Whatever he said was final. You could talk until you were blue in the face, and you weren’t going to change his mind. Most of the time, he was pretty reasonable. John softened these situations by playing the ultimate diplomat. John would never put his foot down and say “This is the way it’s going to be. You’re going to do it my way or hit the bricks.” John always left the door open where you could see some light shining through. There was always hope.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR: The Chopped Camaro

One story that illustrated Charlie Rainville’s practical approach to policing rules happened at Laguna Seca in 1976. Carl Shafer, a regular on the IMSA circuit in his orange Camaro, had towed all the way to California along with a bunch of other East Coast competitors. At the time, IMSA was still building a foothold with the West Coast races and needed every entry it could get. As the Camel GT cars were sitting in pit lane, waiting for practice to begin, Charlie stood next to Shafer’s Camaro, just staring at it long and hard; something just didn’t look right. Charlie called Shafer over and the two of them faced each other. Shafer was 6 foot, 3 inches tall, so he towered over Charlie, who asked him: “The car doesn’t look right, Carl. Did you chop it?” Shafer, knowing he had been caught, looked down and replied in his slow Midwestern drawl: “Yeah Charlie, I did.” Turns out the car’s roofline was four inches too short from the standard Camaro template. But rather than throw him out and not let him race, Charlie told him to weld a four-inch spoiler to the top of his roofline, which the team did that night. It looked like hell and acted as a boat anchor at speed, but at least he didn’t have to tow home to Wyoming, Ill. without racing and IMSA had another car in the field.

Michael Keyser leads the first lap of the Camel GT Challenge race at Laguna Seca in 1976. Al Holbert, Peter Gregg, and Carl Shafer follow. A four-inch spoiler is visible on Shafer’s Camaro, mandated by Charlie Rainville after IMSA found that the roofline had been chopped. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR: Passing Tech Inspection

Jim Busby recalled: “Charlie’s policing was fascinating to me. We’d be doing something really bad, so far out of the box that it was ridiculous. One example was when we modified the wheelbase of a Porsche Carrera RSR to take the weight off the rear end. Having the weight there was great, for the first half of a stint, but we burned off the rears after that. We had to find a way to move weight forward.”

“Right before Mid-Ohio one year, I got to thinking. What if we just move the holes in the fenders forward like three or four inches and move the engine forward three or four inches and misalign the half shafts forward three and a half inches? We made Porsche A-arms that looked stock but moved the wheelbase forward, which shifted the engine and transmission weight forward and shortened the rod that went from the shifter to the transmission and off we went. We took the car to Mid-Ohio and were getting ready to race, but first, we had to get the car through inspection.”

“We’re standing there in the tech shed and Charlie was standing there looking at the car, then looking at me. Over and over again. Back and forth between the car and me, like he was asking with his eyes: “You’re up to something, I just don’t know what it is yet.” Finally, I turned around and I looked at him and he looked at me and he had a look in his eye like, “Is there something you want to tell me?” I responded: “Oh hey, Charlie! How are you?” He nodded his head and walked away. John did that to me a lot too. His patience for me would really grow thin.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Charlie’s stature within the SCCA was solid and influential, particularly the corner workers and other officials. He felt most at home with the hundreds of volunteer officials and course marshals that showed up every race weekend. This allowed him to diffuse some of the early politics that the SCCA had with IMSA. The workers respected him and loved working with him at the track. He quickly added a number of key SCCA stewards, notably, Roger Eandi in California, K.C. Van Niman in the Midwest and Charlie Earwood in the Southeast into IMSA’s fold as race officials. They remained a significant part of the organization for the balance of their careers well into the 1990s.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR: Shicklegruber Fuel Injection

Mark Raffauf remembers a classic Charlie Rainville story: “Charlie worked in the IMSA office in Connecticut a few days a week when there wasn’t a race meeting to attend. Although he was an integral part of the behind-the-scenes rules process, Charlie wasn’t really at home working in an office. He preferred the smells, the grime and the comradery of the track or garage. We were working on finalizing the rule book for the 1977 season when one day, Charlie walked into my office and asked: “What’s the name of the fuel injection that BMW wants us to allow for the 320i?” Both Roger Bailey and I answered: “Kuglefischer.” Charlie thanked us and went back to his office. A month later, after we published the rule book, we received a frantic call from Jim Patterson, who ran BMW’s racing program in North America at the time. Apparently, Charlie had published the rule book with the name of the approved BMW fuel injection as “Shicklegruber,” which is how Charlie apparently translated “Kuglefischer.” We never lived it down with the BMW folks.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

John Bishop and Rainville together forged a philosophy and organization that set new standards of professionalism, communication and empathy that were soon copied everywhere. Although emotions often ran high, drivers respected the decision-making process and often would admit that it was fair, even if it went against their position. Charlie looked out for the competitors in ways very different from previous attitudes about the relationship between officials and participants. They were his drivers and he went to great lengths to take good care of them. And he started every day with a clean sheet of paper, nothing from the previous day was held over anyone.

Charlie Rainville and John Bishop in 1979. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

The staff that worked for IMSA were mentored and taught how to do the right thing, how to be straight-forward and how not to be afraid of making decisions or the resulting consequences. Sure, mistakes were made, but Rainville was generous and forgiving the first time. The second time was not so pretty. From this process, a new generation of professionally trained, full-time officials was developed who eventually held the reins well into the 1990s. Because of this training, when Charlie retired in 1983, the transition to Mark Raffauf was virtually seamless. Though still attending the races for another year he never injected himself into the activity unless asked, but he was always there for support if needed.

When Rainville passed away in February of 1985, sports car racing lost one of its true pioneers. At the time, Ken Parker of the Providence Journal-Bulletin wrote; “No man is irreplaceable, but one cannot help but feel a twinge of sympathy for the person who steps into Charlie Rainville’s shoes. During his many years as Racing (and Technical) Director of IMSA, Charlie was known, loved and respected nationwide, not only for his competence but also his fairness and quiet generosity. John Bishop, President of IMSA, gives Charlie much of the credit for making IMSA the world’s foremost professional racing organization, and Charlie raised IMSA to that level in less than 10 years.”

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” written by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf that tells the inside story of how IMSA got started and its first 20 glorious years. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

______________________________________________________________________________

John Bishop’s early vision for sports car racing in the U.S. was influenced by the Federation Internationale de le’Automobile (FIA), the governing body for all international racing. But his decision in 1980 to create the IMSA GTP category that differed significantly from Group C regulations set down by the FIA the following year wasn’t an easy one. In the end, it resulted in a hugely popular class that would distinguish IMSA and racing in North America from the rest of the endurance racing world for more than a decade.

By the mid-1970s, the FIA class structure (Groups 1-6) for endurance racing was floundering in Europe, while IMSA’s race entries were growing. IMSA’s success did not go unnoticed by the FIA and the organizers of Le Mans, the most prestigious event on the international sportscar calendar. In 1976, an event partnership between Daytona International Speedway and the Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO), the Le Mans organizers, brought IMSA’s popular Corvettes and Monzas to the famed French 24-hour race, where they ran in a special class. John Greenwood’s Corvette and Michael Keyser’s Monza both ran strongly, even leading the Group 6 prototypes early in the race. Greenwood recorded the fastest top speeds on the Mulsanne straight that year, an astounding 215 mph. Although both cars were eventually forced to retire with mechanical woes, non-homologated American cars from IMSA were making a mockery of the FIA rules structure.

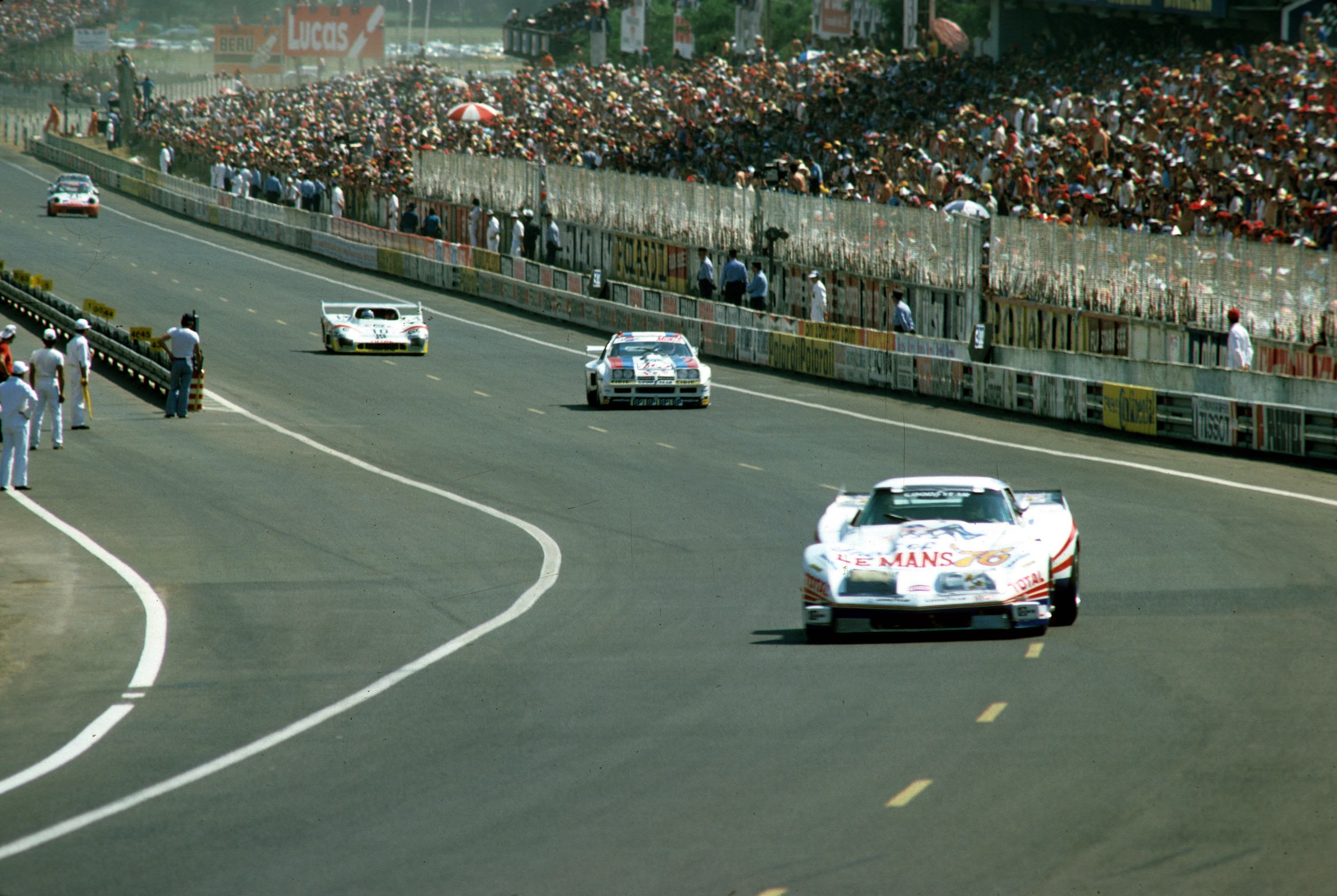

In the early laps of the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1976, John Greenwood’s Corvette leads Michael Keyser’s Monza and the eventual runner-up Group 6 Mirage Ford GR8. The IMSA class cars were popular with the fans and ran strongly before both dropped out with driveline/transmission problems. Photo: autosportsltd.com

The situation led to a new and productive relationship between Bishop and Alain Bertaut, the Director of Competition for the ACO. Both men shared similar values and appreciation for giving the private entrant a fighting chance. They also agreed that controls were needed to reign in the rapidly escalating costs of competition. But most importantly, they saw eye-to-eye on the importance of putting on a good show for paying spectators.

Bertaut, Bishop and Bill France Sr. began working together to encourage participation by the same teams and manufacturers in the 24-hour races at Daytona and Le Mans, including an invitation by the ACO for NASCAR stock cars to race at Le Mans in 1976, when NASCAR drivers Dick Brooks and Dick Hutcherson drove a Junie Donlavey-entered Ford Torino. Eventually, an entire class was devoted to IMSA at Le Mans due to the cars’ popularity with the European fans, a situation that lasted through the 1982 race.

The first turbocharged Porsche 934 ever to race anywhere in the world was at the 24 Hours of Daytona in January 1976, eligible only by special invitation to the World Championship of Makes Manufacturer championship. It finished forty-first, dropping out with mechanical issues. Photo: autosportsltd.com

In a reciprocal arrangement, European-based cars were brought to the U.S. to race in the 24 Hours of Daytona, including the first Porsche 934 to race anywhere in the world in 1976, and the Inaltera built by Jean Rondeau that raced in 1977. The first Porsche 935s showed up at Daytona in 1977 as well, even though they were not yet eligible to compete in other Camel GT races. The Inaltera was entered in the “Le Mans GTP” class, a catch-all for cars that did not meet FIA Groups 1 through 6 regulations or anything else, and had been conceived by the ACO as a cost-effective alternative to Group 6. Over the years, the Le Mans GTP class included the WM-Peugeot, Rondeau 378 and the Porsche factory 924 Turbo GT cars.

The Martini & Rossi–sponsored factory Porsche 935 and a similar Kremer customer car were the first 935s to compete in an IMSA event, shown here on the front row of the grid at the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1977. Inaltera “Le Mans GTP” prototypes are on the second row. Both car types competed as part of the World Championship of Makes. Photo: ISC Archives & Research Center/Getty Image

The IMSA-ACO relationship continued to grow. IMSA representatives regularly attended the 24 Hours of Le Mans to build relationships and help the U.S. teams participating there. Dick Barbour, Paul Newman, and Rolf Stommelen driving a Garretson-prepared Porsche 935, almost won the race overall in 1979, driving an IMSA-class car. All the signs pointed to a flourishing relationship between IMSA and the ACO, with movement toward a uniform set of technical rules that would guide both sides of the Atlantic.

The relationship flourished to the point that Bertaut traveled cross country in the Bishop’s Newell Coach during the summer of 1980 and the following year his daughter interned at the IMSA headquarters. The ideas that resulted in IMSA’s GTP class were hatched on that long cross-country drive in the motorhome. The class was envisioned as a simple prototype car governed by a sliding power-to-weight formula that would be attractive to both manufacturers and private constructors. Jean Rondeau had shown the way by winning Le Mans in June of 1980 in a car designed and built entirely in his garage, fitted with a detuned Cosworth customer Formula One engine.

From Bishop’s point of view, Porsche and its 935 were dominating the 1979 and 1980 seasons and he knew that it would be difficult to continue growing the Camel GT Series unless something changed. Although the racing was close, he worried that no one would continue to pay to see a Porsche parade. The AAGT concept had diversified the fields for a while, but the cars were increasingly uncompetitive against the onslaught of 935s, even with more relaxed GTX rules that allowed for tube frames, wider wheels and essentially unlimited bodywork tweaks. BMW, Nissan, and Ford had all been represented in the GTX class during this time, but only as solo or two-car efforts; there were no customer cars. And the price for a new Porsche 935 was in excess of $200,000, a huge sum at the time. Privateers were getting priced out of the game.

“The bottom line is that private entrants fielding American-powered cars were never going to be able to keep up with the money invested by large manufacturers like Porsche, who were continually developing customer cars with virtually unlimited funds,” remembered Bishop. “We needed something new. We liked the general direction that the ACO and FIA were taking that allowed entrants to pair prototype monocoques with different engines, but somehow the Group C rules had become driven by fuel consumption as a result of the recent gas crisis. The Europeans seemed out of touch with what sold tickets in the U.S. We didn’t think fans wanted to watch high-powered racing cars coast by in an effort to save gas to make it the end of the race.”

“We were initially inspired by the Inaltera cars that showed up for the 1977 24 Hours of Daytona in a special prototype class,” Bishop continued. “The cars were fast, good looking and competitive. Best of all, they were built with off-the-shelf parts by Jean Rondeau, a private entrant, so we knew it could be done on a reasonable budget. Given the availability of a wide variety of reliable engines, our vision was to repeat a bit of the same formula that had made the AAGT class such a success. Our goal was to create a prototype class that could compete head-to-head with the 935s, but at a lower price point.”

One of two Inaltera “Le Mans GTP” class cars during the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1977. The privately designed and built machines became the inspiration for the IMSA GTP class rules developed in 1980. Photo: autosportsltd.com

After Rondeau’s victory at Le Mans in 1980, the IMSA-ACO relationship continued to gain steam. By contrast, the FIA’s World Championship of Makes continued to lose traction. Grids were small and participation by manufacturers sporadic. After much hand wringing, the FIA announced a response in 1980. It would abandon the Group 1 through 6 model and revamp all technical regulations into a new structure of Groups A, B, and C. Group A encompassed touring cars, Group B included GT cars along with limited production touring cars, and Group C defined sports prototypes.

There was one problem: IMSA had already publicly committed to the GTP concept as the alternative to the dominating Porsche 935. By the time of the FIA’s announcement on Group C, the GTP concept was well underway with chassis layout, engine options and a weight/displacement scale already decided on with mutual IMSA/ACO support. And manufacturers like Lola, BMW, and March were already building cars.

The hope was that all parties would embrace the IMSA GTP concept given that IMSA and the ACO were aligned and cars were already being built. However, the FIA went in another direction for its Group C class rules by insisting on a fuel consumption formula for the World Championship of Makes.

Without Le Mans on the World Championship of Makes calendar, it was doubtful whether the FIA series could survive. With an impasse looming over which rules would be used at Le Mans, the FIA, through its control of the World Championship of Makes, decided to play hardball. Jean-Marie Balestre was the president of the FISA – the sporting arm of the FIA – and also happened to be the president of the organization that controlled auto racing in France known as the Fédération Française du Sport Automobile. Wearing both hats, Balestre threatened to not to list the 24 Hours of Le Mans as an international event unless the ACO adopted the new Group C regulations along with the fuel consumption format. The ACO was forced into a corner, because not being listed would create licensing and legal havoc, among other problems. Although Bertaut was more philosophically aligned with IMSA, he had no real choice but to acquiesce to the political pressure in France. The ACO agreed to adopt the FIA Group C formula.

Although IMSA GTP and Group C cars turned out to be very similar, there were three critical technical differences that would keep them apart. IMSA required the driver’s feet to be behind the centerline of the front axle for safety reasons from the earliest time the rules were drawn up. Second, the fuel consumption formula favored smaller displacement, predominantly European racing engines that did not offer privateers, American or Japanese brands an equal opportunity to succeed without significant investment in new technologies. And finally, IMSA GTP rules required the use of production-based engines.

Due to these fundamental divides, IMSA went its own way. IMSA GTP chassis from Lola, March, Jaguar, and Ford appeared by 1983 and won the championships in 198 and 1983 through 1993. With the introduction of Group C in 1982 first at Silverstone and then at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the IMSA class subsequently fell away at the famed event. The Group C specifications did help the newly renamed World Endurance Championship of Makes regain its footing in Europe and became the World Sports-Prototype Championship in 1987. At the same time, IMSA grew and succeeded with the IMSA GTP concept in the U.S. Meanwhile, Japanese rule makers developed a similar, but unique style of prototype racing in Japan that didn’t exactly match either Group C or IMSA GTP.

By 1984, IMSA Camel GT fields were packed with GTP machines, as illustrated here at Michigan International Speedway. A Ford Mustang GTP leads from a few March chassis, two Jaguars, two newly introduced Porsche 962s and others. Photo: Bob Harmeyer

As a result, three separate prototype championships evolved that dominated their respective markets for over a decade. Ironically, this became the most successful period of global sports car racing in history. Manufacturers that participated in Group C included Lancia, Porsche, Mercedes, Ford, BMW, Nissan, Jaguar, Toyota, Mazda, Rondeau, Sauber, Spice, Lola, Argo, Tiga, and Alba, among others. A similar group or road car and racing car manufacturers participated in IMSA: Porsche, Jaguar, Nissan, Mazda, Ford, BMW, Toyota, Acura, Spice, Argo, Tiga, and Alba, in addition to U.S brands Chevrolet, Buick, and Pontiac. In Japan, Nissan, Toyota, Mazda, and Porsche all took part. Not all of these brands necessarily participated in each series at the same time, but the U.S. market drove the creation and development of more manufacturer GTP cars than either of the other two series.

The technical situation changed in the FIA after some frightening accidents in Europe. In 1985, the FIA finally adopted the IMSA rule concerning the placement of the driver’s feet behind the front axle centerline. With this change, a common chassis could then be used around the world in the European-based World Endurance Championship of Teams, the U.S.-based Camel GT Series, and the Japanese Sports Prototype Championship.

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” that tells the inside story of how IMSA got started and its first 20 glorious years. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

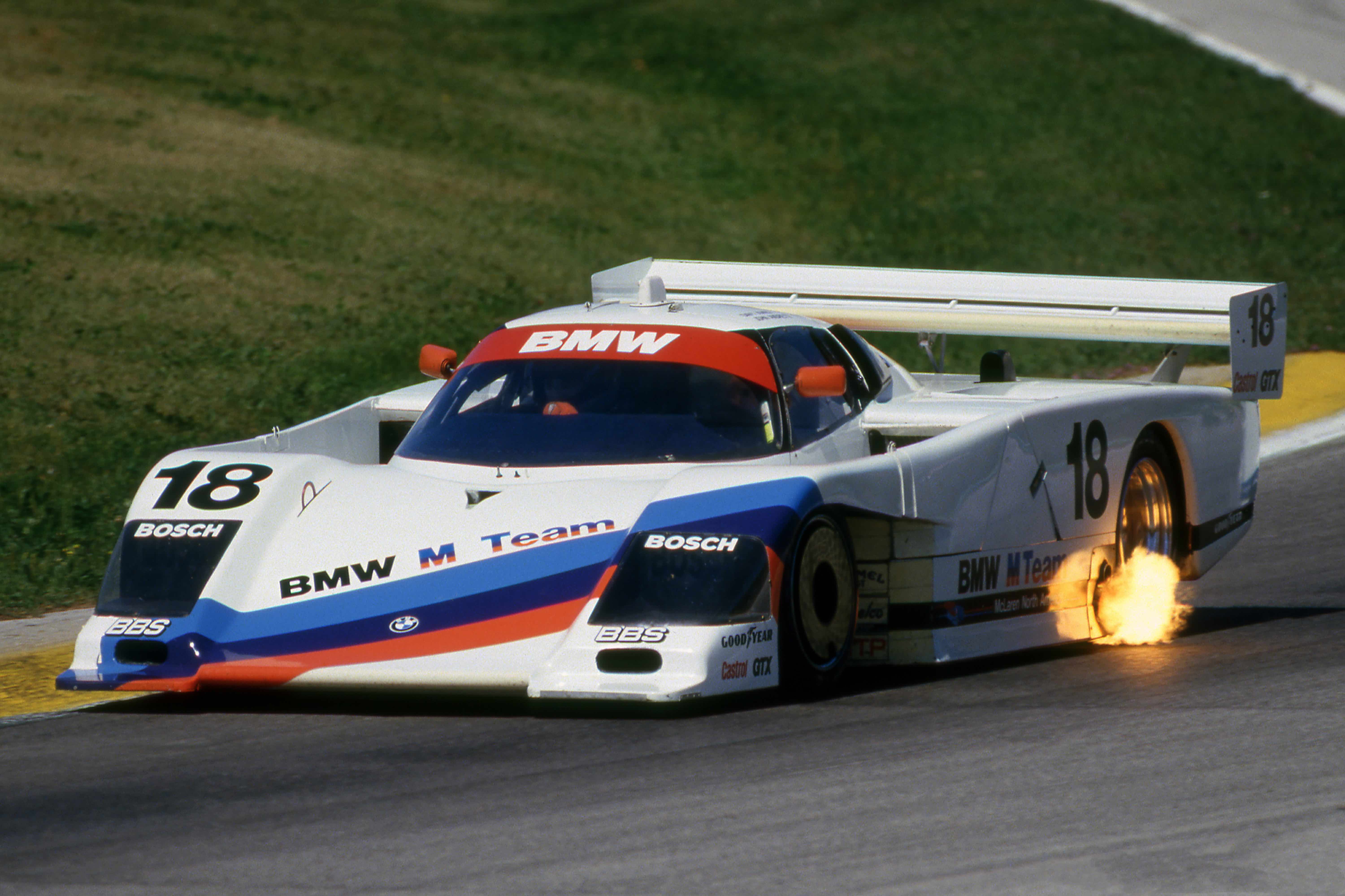

BMW of North America’s racing group was established in 1975 in an effort to support the company’s growth in the lucrative US performance car market. Unfortunately, the company did not have an IMSA championship to show for the investments in the BMW 3.0 CSL and the turbocharged BMW 320i. With just one or two cars pitted against a host of Porsches, the odds were not in their favor. The tube frame M-1 Procar did crush the GTO competition in 1981 but was underpowered in IMSA’s top GT Prototype (GTP) class.

Something had to be done to narrow the gap. Former SCCA executive Jim Patterson, who took over the BMW North America racing program in 1978, saw the newly minted IMSA GTP rules in 1980 as a way to get back in the game. Working with partner March Engineering, a unique new prototype was unveiled in early 1981 that would become the basis for a long, successful supply of GTP cars to the IMSA field from the British company.

The BMW M1/C debuted at Riverside in April 1981. The March chassis featured a modern aluminum monocoque that was mated to a normally aspirated 3.5-liter BMW engine. The team would upgrade to a 2.0-liter turbocharged motor later in the year. Photo: Don Hodgdon

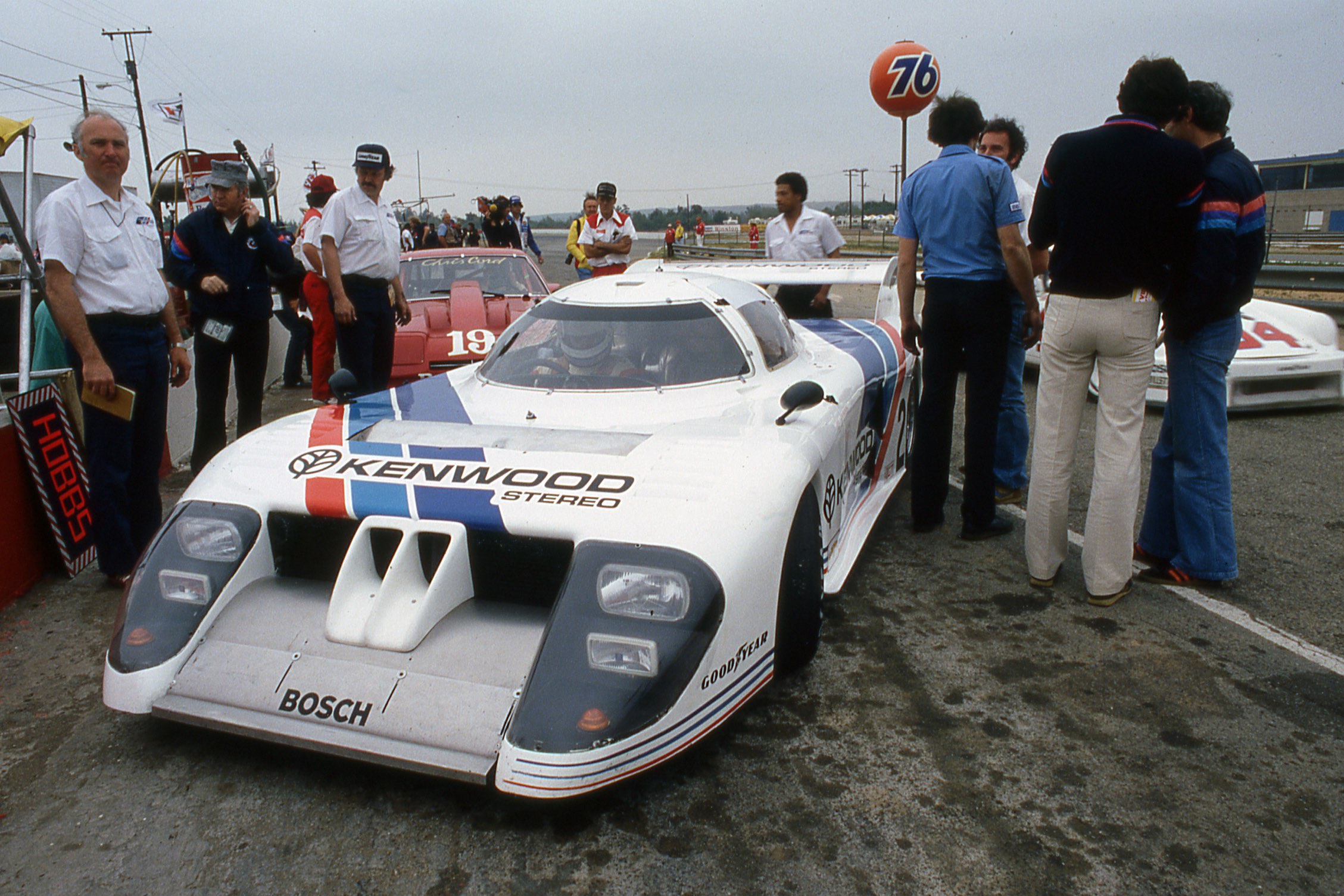

Designed by French aerodynamics expert Max Sardou and BMW engineer Raine Bratenstein, the car was dubbed the BMW M-1/C. It was built around a March Engineering aluminum monocoque and featured two distinctive pontoons at the front that were designed to channel airflow to both the radiators and twin ground-effects tunnels for maximum downforce. The car was initially fitted with a 3.5-liter, six-cylinder, normally aspirated BMW engine, and entered for the first time at the Riverside 6 Hours in April 1981 with David Hobbs and European endurance veteran Marc Surer at the wheel. Featuring sponsorship livery from Kenwood audio, the pair finished a credible sixth place, albeit eleven laps down to the winning 935 piloted by Fitzpatrick and Busby.

The lone BMW M1/C is swamped by a host of Porsche 935s at the start of the 1981 Riverside Camel GT race. The M1/C would go on to finish sixth, eleven laps down from the winning Porsche 935 of John Fitzpatrick/Jim Busby (#1). Photo: Don Hodgdon

A week later at Laguna Seca, Hobbs placed sixth again, this time one lap down to the new Lola T-600 with Brian Redman at the wheel. Although down on power, Hobbs managed to put the car on the front row at both Lime Rock and Mid-Ohio. The first few races proved the M-1/C had real potential and the decision was made to further develop the chassis and engine. The long-term plan was to install the 1.5-liter turbocharged BMW motor being developed for Formula One, but that engine wasn’t ready and would never be used in the March. Instead, the team force-fit the same turbocharged 2.0-liter, four-cylinder engine that had been used successfully in the McLaren-engineered BMW 320i program. Since the M-1/C had not been designed for that power plant, it required a cooling workaround for a motor that produced 600 to 675bhp with the boost turned up.

Results were mixed after the change. The new engine debuted at Sears Point in August. The car was fast and competitive, but ultimately unreliable. A fourth place at Portland would turn out to be the team’s best finish. Despite stating long-term commitments early on, BMW again left IMSA racing at the end of the year, this time to focus on its Formula One program.

Even with this setback, March Engineering took what it had learned from the M-1/C experience and produced a viable, stable GTP customer car for 1982, dubbed the 82G, that was designed by Gordon Coppuck. The first two customer March 82Gs appeared in January for the 24 Hours of Daytona. One of them was a Chevrolet V8-powered version driven by Bobby Rahal and Jim Trueman and fielded by Garretson Enterprises. Rahal would campaign the car in later rounds with Michelob backing.

The first March 82G customer car was fielded by the Garretson team at Daytona in January 1982. Photo: Bob Harmeyer

The other March was campaigned by Dave Cowart and Kenper Miller’s Red Lobster team. After winning the 1981 GTO championship in the dominant BMW M-1, the team commissioned an 82G from the March factory with the now well-tested 3.5-liter BMW M-1 engine. The distinctive twin pontoons of the March turned out to be a perfect canvas for two Red Lobster claws, a design that became iconic almost instantly. Unfortunately, the normally aspirated BMW engine was no match for the Chevy V8 or Porsche 935s, and for 1983 the team campaigned with Porsche 935 turbo power, only to suffer from overheating issues. The team took the midsummer Daytona race off in 1983 and came back later in the year with Holbert’s second March 83G powered by a Chevy V8.

The twin pontoons of the March 82/3G were ideally suited for the paint scheme of the Red Lobster team, pictured here in 1983 at Daytona, leading the similar Porsche-powered March of Al Holbert. Photo: Richard Bryant

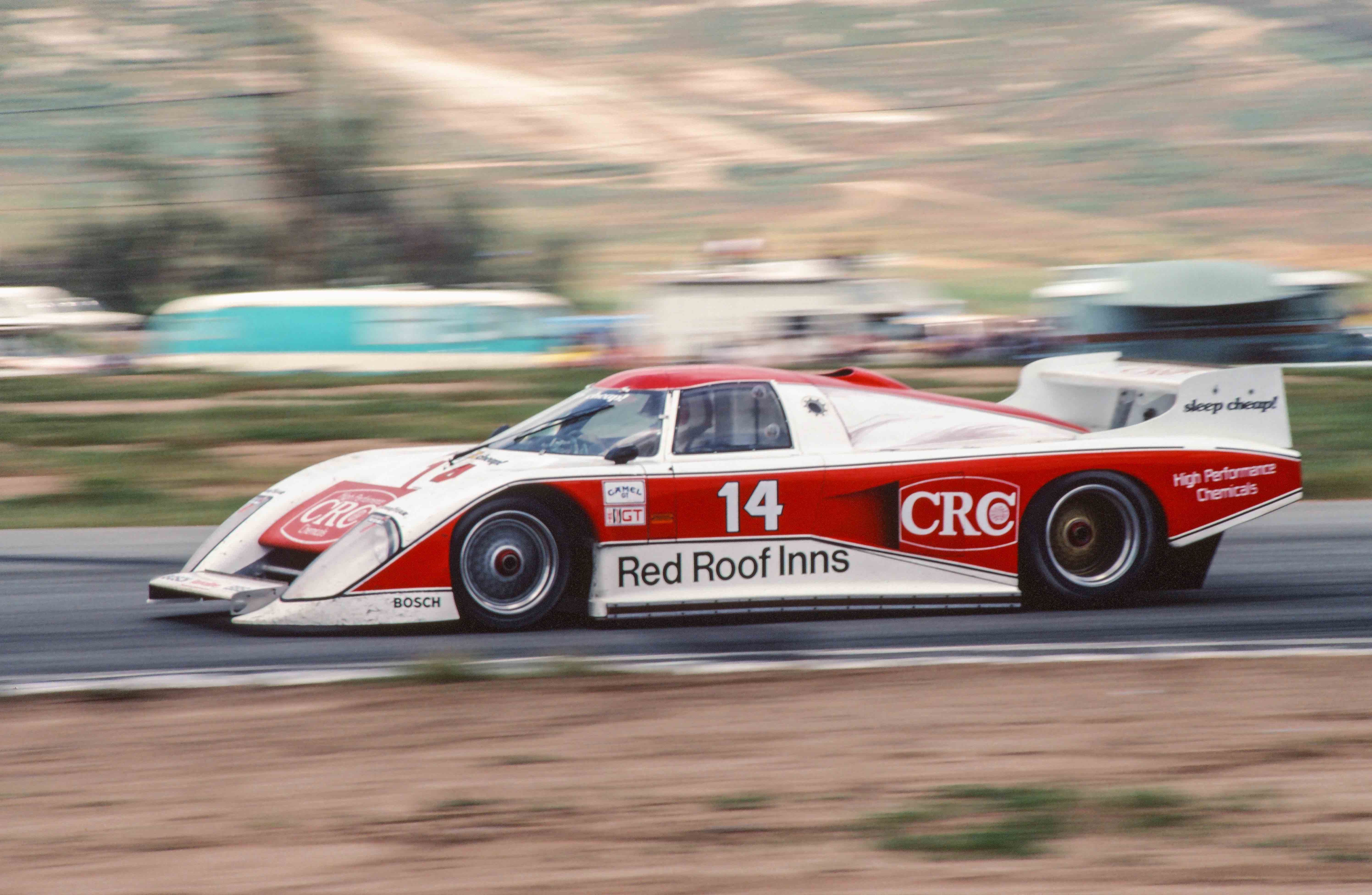

The biggest news of the 1983 season was the return of Al Holbert, who had been pursuing Indy Car and Can-Am glory. Holbert started the season by sharing Bruce Leven’s Bayside Disposal 935 with Hurley Haywood at Daytona and Sebring. But his main focus was on a CRC Chemicals–sponsored March 83G, initially fitted with a small-block Chevy V8. Holbert won with the car the first time it was entered, at the inaugural, but rain shortened, Grand Prix of Miami. After skipping the Road Atlanta round, Holbert finished second at Riverside and won Laguna Seca, after which he sold the car to Kenper Miller and Dave Cowart’s Red Lobster team.

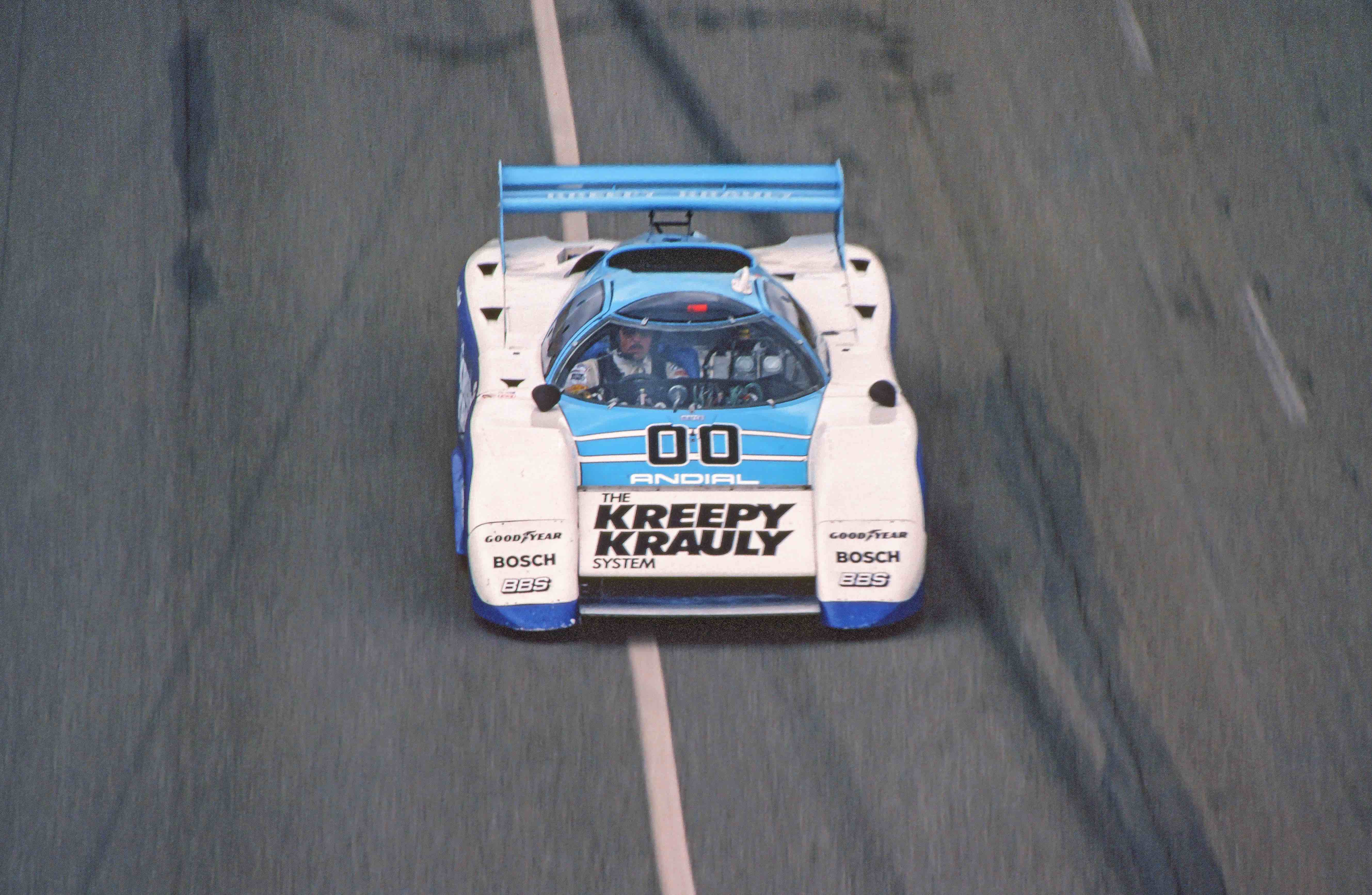

Holbert had another ace up his sleeve: a brand-new March 83G, this time fitted with an ANDIAL-prepared Porsche 934 single-turbo engine. Despite skipping the Mid-Ohio and mid-summer Daytona events, Holbert easily took the 1983 Camel GT title by winning with the new Porsche-powered car four times and scoring points in another seven races.