By Terry O’Neil

Brands Hatch Circuit, situated in the rural county of Kent, was the venue for the eighth round of the Manufacturers’ Championship for prototype cars on July 30, 1967. It was the first time that Brands Hatch had been used for the series and the drivers found that it was quite different from the other continental venues that had their long sweeping curves and lengthy straights. By contrast, Brands Hatch was shorter in length, 2.7 miles, with hills and tight corners to contend with which proved a challenge to the engineers who were responsible for setting up the cars.

Whilst Ferrari just missed out on victory in England at Brands Hatch on that day, the results were significantly good enough to help Ferrari achieve its ultimate goal for 1967 in winning the Manufacturers’ Championship for prototype cars, thus taking revenge on Ford who had just pipped Ferrari to the Championship in 1966, and Porsche who had been leading the Championship up to this point in 1967.

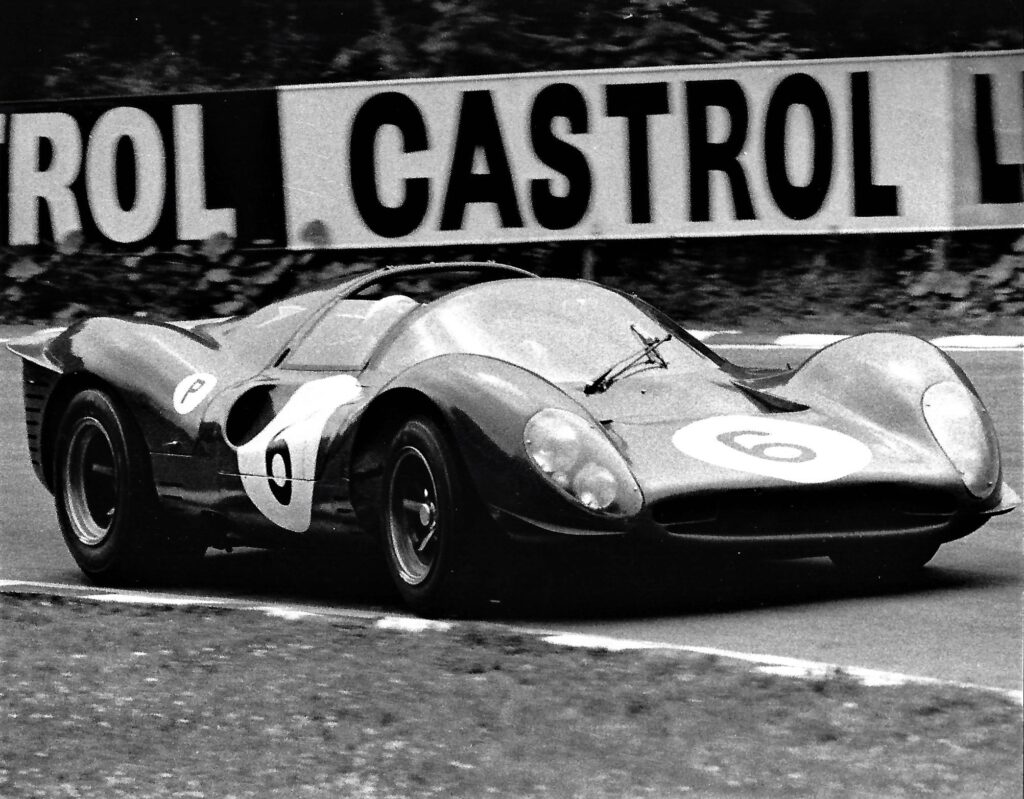

Sefac Ferrari sent three identical open-top 330 P4s for Amon / Stewart, Scarfiotti / Sutcliffe, and Hawkins / Williams, while a 412P was entered by Maranello Concessionaires for Attwood / Piper. Lined up against them and determined to secure the Championship were five Porsche Works entries consisting of four 910 models for Hill / Rindt, Siffert / McLaren, Elford / Bianchi, Schutz / Koch and a 907 model, the latter for Herrmann / Neerpasch to drive.

The Scarfiotti / Sutcliffe Ferrari P4 making one of its two planned pit stops for fuel and driver changeover.

Five American V-8 engined cars were also competing in the prototype category. A Chaparral 2F was prepared for Spence / Phil Hill, three Lola T-70 cars for Hulme / Brabham, Westbury / DeUdy, and Surtees / Hobbs and a Mirage for Thompson / Pedro Rodriguez. Altogether there were twenty-one prototype cars entered into the race which also included fourteen cars entered in the Sportscar Championship class. It was in this category that Ford came to the fore, where four GT40s were up against three Ferrari 250LMs in the over two-liter class and three Porsche 906s in the under two-liter class.

Qualifying ended with two Lolas and the Chaparral on the front row of the grid, two Ferrari P4s on the second row, and the third row having two Porsche 910s and the other Ferrari P4 in place. Surtees’ Lola led off from the front row followed by Hawkins and Scarfiotti in P4s from the second row and Spence in the Chaparral.

The Ferrari P4 driven by / Williams led the race briefly but finished in sixth place having covered 204 laps.

Hawkins took the lead on the second lap, with Hulme inching ahead of Phil Hill for fifth place. Hawkins’ lead would prove to be short-lived as first Hulme and then Spence and Scarfiotti went past him, relegating the Ferrari 330 P4 to fourth place.

Over the next few laps, Hulme began opening up a gap and set the fastest lap of the race in the process. Behind him, Spence and Scarfiotti were holding down their positions waiting for Hulme to falter. They didn’t have too long to wait as on the hour Hulme’s Lola coasted into the pits and out of the race with a broken rocker arm. Spence, having inherited the lead, made the most of his opportunity with a clear track ahead of him, using the powerful Chevrolet engine to open up a gap before coming into the pits for a driver change-over with Phil Hill, and losing the lead as Rodriguez with the Mirage had climbed up the field and had the momentum to take over the lead, with Siffert’s Porsche behind him. It was to be a short-lived situation because neither of the cars had pitted yet, so when they did Hill in the Chaparral regained the lead.

After the round of pit stops the action on track became frantic, as Phil Hill had to make his way to the pits with a flat tire, and Dick Thompson undid Rodriguez’s hard work by spinning the Mirage into an earthen bank on lap 87, and out of the race.

A Ferrari P4, #6, was driven by Chris Amon and Jackie Stewart to second overall, covering 211 laps, sealing the Manufacturers’ Championship for prototypes for Sefac Ferrari.

At half distance, the Amon / Stewart Ferrari P4 led the way from the Siffert / McLaren Porsche 910, Phil Hill’s Chaparral, and the Hawkins / Williams Ferrari P4. Generally, the attrition rate was low, with only seven of the thirty-five starters pulling out of the race. With the Porsche driven by Graham Hill being one of those cars, the Porsche team made a tactical change to their driver pairings and replaced Koch with Rindt in the Schutz car as the Austrian was quicker than Koch.

The Ferrari 412P entered by Maranello Concessionaires and driven by Piper and Attwood to a seventh place finish, covering 202 laps.

Having spent a considerable amount of time in the pits because of fuel problems in the first half of the race the Surtees / Hobbs Lola made it up to seventh place before the engine seized, ending its race, giving Hawkins breathing space, as he had troubles of his own when the rear bodywork of his Ferrari came adrift and he had to pit to have it wired back together again.

The next series of driver changes put Spence back in the Chaparral in front of Siffert’s Porsche 910 and Amon’s Ferrari P4 with Spence widening the gap at the front as each lap went by. Attention was drawn to the battle for second place which would effectively decide the outcome of the prototype championship. Less than two hours of the race remained when Siffert pitted for the final time, and after an efficient stop came out in third place behind Amon, but knew that Amon would also have to stop soon. Amon was motoring in top form and building a cushion over the Porsche which was now heavy with fuel again. At the last possible moment, Amon pitted, stayed with the car, and was out on track again within forty seconds and having a cushion of a minute to the Porsche. It was enough to secure the second spot as Siffert’s Porsche could do nothing to put up a challenge. The Porsche team had to accept defeat in the prototype championship by a five-point margin.

Meanwhile, the Chaparral motored on without any unforeseen trouble to take the overall victory with only Amon’s Ferrari on the same lap as the Chaparral as the flag fell.

The first car in the Sports Car category to finish was the Porsche 906 driven by Tony Dean and Ben Pon in eighth place overall, ahead of the Ferrari 250LM driven by Hugh Dibley and Roy Pierpoint.

Part 1: From Small Beginnings

Following World War II, the United States economy was beginning to grow slowly during the time of peace, benefiting the everyday requirements of its population. Along with its growth, a demand for increased leisure activities prevailed.

Motorsport had been one of the last leisure activities to recover for several reasons. Some pre-war established race drivers had either been injured or did not return from the war and as a result race track owners had a hard time re-establishing the level of competition to satisfy their customer base. Add to that the fact that domestic production of cars had only just geared up again, with the consequence that cars for use other than being a family necessity were not easy to come by.

However, the mid-1950s were witness to a change in fortunes for a few people who were lured by the growing number of sports cars coming into America from Europe. It was from this group of people that a small number of owners in and around the New York area took it upon themselves to form a club. Firstly, because they enjoyed their cars, and secondly because it was their aim to enter them into races, and hopefully win monetary prizes – something that was not possible by being a member of the Sports Car Club of America.

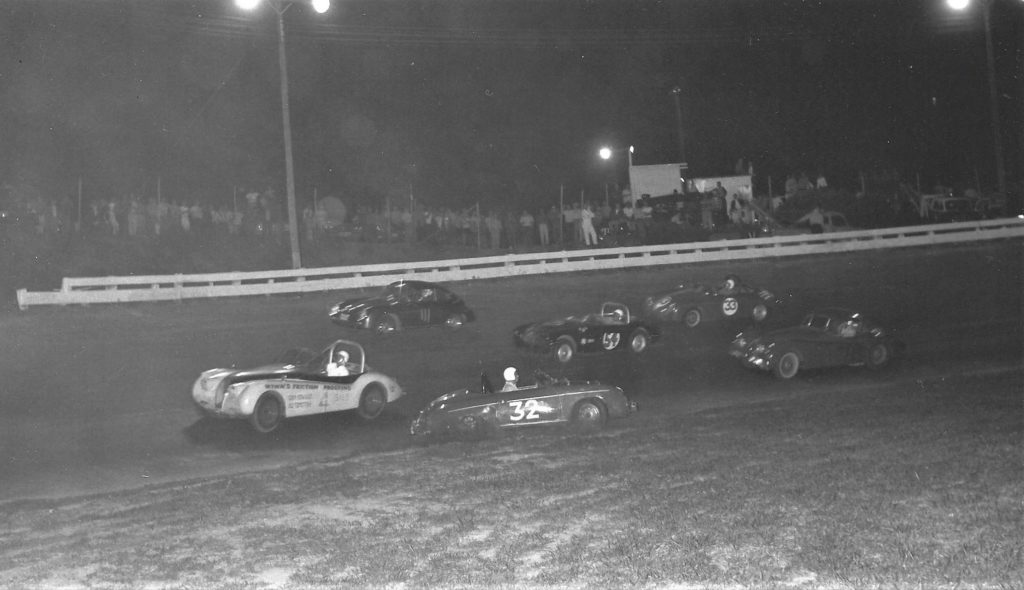

It was decided that the club would be known as the Sports Car Owners and Drivers Association (henceforth called SCODA in this article), and it was officially incorporated in New Jersey on October 1, 1954. The Club was based on Long Island with Bill Claren appointed as its first president. Claren, with Stan Becker, Joe Ferguson, and Ray Erickson, took the decision to administer the Club from Long Island despite the presence of the established Long Island Sports Car Club in that location. One of the Club’s first actions was to affiliate itself with NASCAR and approach any dirt track or oval that would consider including a sports car race into their program of Midget or Stock car races. This was not quite as audacious as might first appear as the track race organizers knew some of the SCODA members and were already holding NASCAR-sanctioned race meetings.

The strategy appeared to work well as SCODA’s traveling road show offered short track promoters variety for their weekly programs, something that was a welcome added attraction for the spectators. So much so that the track organizers were prepared to put up some prize money for the drivers. The money that changed hands was modest, the total purse averaged about $1,000, and of that, the winner’s share was around $200. With the swift introduction of appearance money in 1954, everyone headed home with something in their pocket.

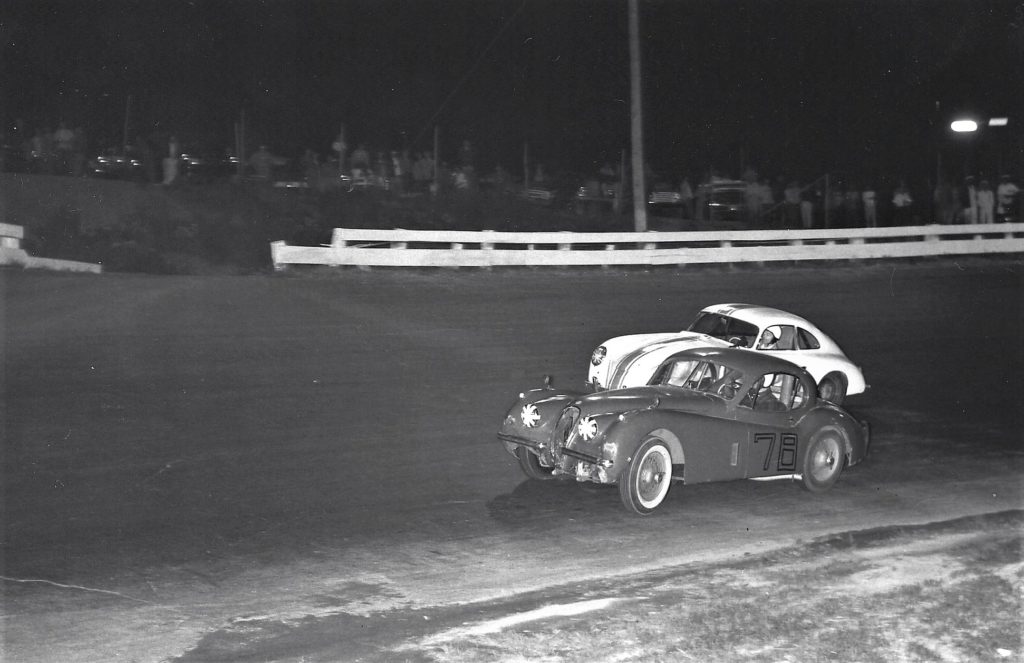

Through their affiliation with NASCAR, SCODA was able to utilize some of the many speedway ovals which existed in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states of America during the 1950s, often forming part of the larger racing program. Not only did they race for money, but they also formed their own race championship series, possibly the first club in America to do so outside of the SCCA. Their format for the championship was quite simple, the cars being divided into either the under-1500cc or over-1500cc category with points awarded for finishing positions in the feature race at each venue. It remained that way for several years before a change was made. (It should be noted that SCODA had always taken a rather wide view on the exact definition of a sports car, with a number of creative interpretations turning out at some of the meetings. As long as the cars met the technical and FIA specifications the cars were allowed to compete. A typical race meeting format would be to have heats, semi-final, consolation, and a feature race in the same manner as the Midget and Stock Car events.

Through their affiliation with NASCAR, SCODA was able to utilize some of the many speedway ovals which existed in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states of America during the 1950s, often forming part of the larger racing program. Not only did they race for money, but they also formed their own race championship series, possibly the first club in America to do so outside of the SCCA. Their format for the championship was quite simple, the cars being divided into either the under-1500cc or over-1500cc category with points awarded for finishing positions in the feature race at each venue. It remained that way for several years before a change was made. (It should be noted that SCODA had always taken a rather wide view on the exact definition of a sports car, with a number of creative interpretations turning out at some of the meetings. As long as the cars met the technical and FIA specifications the cars were allowed to compete. A typical race meeting format would be to have heats, semi-final, consolation, and a feature race in the same manner as the Midget and Stock Car events.

In 1954, nine championship races took place at various oval tracks located in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, with a total purse of $9,500 on offer. The first race took place on a one-quarter-mile paved oval at Plainville Stadium on July 3, where Bill Claren took the feature race in his Jaguar XK120. He followed his victory up the next evening when he appeared at Wall Stadium in Belmar.

Morristown Speedway was the next venue, and this time it was Ed Schaefer who took the honors and the lion’s share of the purse, driving Paul Whiteman’s Jaguar XK120. Despite some stern opposition from the likes of Stan Becker’s Ford and Bill Boyd’s Miller Special (a 1927 model brought up to sports car specification with added fenders and a Corvette engine), the Jaguars looked unbeatable in these early races. A large field of entrants appeared at Hatfield Speedway, all keen to try out the recently laid “rubberised asphalt” that had been spread over the one-half-mile oval. However, the result was the same as the Jaguar XK120 driven by Pete Bell headed five other Jaguars to the flag. In the under-1500cc section, a selection of MGs performed well, though had no chance of obtaining good overall positions.

Jim Reed won at Roosevelt Stadium in September on the one-quarter-mile track in his Jaguar XK120, but the results from other races for 1954 have eluded me, though it would appear Bill Claren must have been among the front runners as he was awarded the 1954 SCODA driver’s championship.

Buoyed by the success of the 1954 season, SCODA’s progression appeared to be inevitable. In 1955, it was reported in National Speed Sport News that SCODA would be willing to sign up for races within a 200-mile radius of New York City and had up to fifty cars and drivers ready to race. It also sent a signal to the SCCA: “Despite the accepted standard that sports car enthusiasts do not race for money, a little group of aficionados from the New York area are kicking over the traces and if their early success is a portent of things to come, the old traditions may be in danger.”

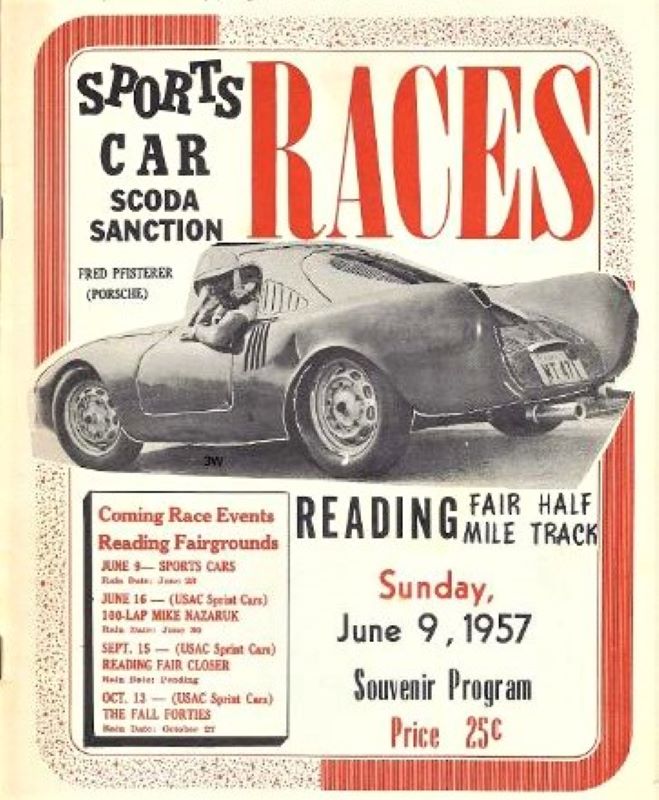

The program of events expanded for 1955 with 11 meetings taking place, the Civic Stadium in Buffalo being the furthest venue from New York City, and had an expanded purse of $14,250. With the increase in membership came some more competitive cars. Fred Pfisterer who had previously raced with the SCCA brought along an Austin-Healey 100-6 in place of his MG and Nick Caviluzzi a highly tuned Ford Thunderbird. Pfisterer broke the Jaguar stranglehold by winning the first race at Virginia Beach Speedway and then at Altamont Speedway, whilst the Ford Thunderbird bullied its way to victory at Williams Grove Speedway and Hatfield. Pfisterer’s consistent high-place finishes gave him the 1955 SCODA championship ahead of Nick Caviluzzi, with Stan Becker in the third spot. Despite Bill Claren winning a couple of races in his Jaguar, he could do no better than place fourth in the rankings.

By 1956, SCODA was an organization to be taken seriously as more and more drivers joined the club, bringing with them an array of machinery that would have graced many an SCCA race.

The number of races that took place has been impossible to verify due to a couple of factors. Firstly, there were now two classes of vehicles and in both classes there were “race winners.” Secondly, the press did not always report on the race meetings that took place. Adverts for forthcoming events meant little due to cancellations caused by inclement weather on the day.

Within SCODA there was an election for officials with Stan Becker elected as the 1956 president. Other officials elected were Fred Pfisterer, Nick Caviluzzi, Bill Boyd Hanauer, Jake Jacobs, and Pete Mourad.

Sixty-three members registered to compete in the races, and between them, they used seventy-five cars in the season. Two Chevrolet Corvettes started the season strongly, taking first and second places at Raleigh Speedway and Martinsville Speedway, though by June it was Jake Jacobs who was on the top spot of the podium. He had started the season in his MG-Cadillac, but then changed to driving a Jaguar XK120 using a Corvette engine, in which he won many of his races. It was suggested in the press that he had entered 28 races including heats and won 19 feature races. Whilst that appears excessive, his points tally for the season was nearly 200 above the runner-up, Fred Pfisterer, who won the under 1500cc section, so it was certainly a highly successful and profitable season for him.

At the 1957 AGM an important decision was made that in some ways would turn the fortunes of SCODA, though in hindsight, not for the better. With the confidence of two years of success and growth within the club, the SCODA Board of Directors voted to cut SCODA’s ties with NASCAR, and to sanction its own races. However, because of prior commitments to the 1957 program, some of the venues continued to have NASCAR sanctions and it would be another year before SCODA fended for itself. At least 13 events took place during the year including races at new venues: Reading Fairgrounds in Pennsylvania and Rutland Speedway in Vermont.

Bill Boyd’s introduction to the one-half-mile dirt oval at Rutland was one he would have wanted to forget as on the second lap of the feature race he was involved in a four-car accident in which his Miller-Corvette Special flipped over. The race was stopped and Boyd was taken to the hospital. Luckily he survived though his car was wrecked.

The highlight of the 1957 season was the performance of Charles Bettman in the under 1500cc section of the Club’s races. He entered 10 events and won them all driving a VW-Porsche Special, a feat that out-stripped the over-1500cc class winner Bob Ellis. However, Ellis gained more points to take the overall title by entering more races and consistently ending up on the podium.

Part 2: Changes Abound

With SCODA operating independently from NASCAR in 1958, it brought in a few changes for the season. It had long been debated within the club as to whether the cutoff point between classes of cars should remain at 1500cc. Although there was a strong feeling that it should remain that way, the board of directors decided that a change to 1600cc would be in place for 1958. The gesture turned out to be more significant than the reality, as there appeared to be precisely the same cars competing in each class as in 1957.

Two new venues were added to the program for the year, Danbury Fairgrounds, which started out as a dirt track but was upgraded by owner John Leahy into a one-third-mile asphalt oval, and Riverhead Raceway on Long Island under promoter Ed Hawkins’ banner. As well as having its own schedule of races SCODA was invited to attend a meeting at Soldier Field, Chicago, though the results of this race meeting did not count towards the SCODA championship.

Originally there were 14 planned races for 1958, but four were canceled due to bad weather. As a consequence, the available purse money diminished from $16,950 down to $12,350.

The first race meeting was held at the Orange County Fairgrounds located in Middletown, New York, where the feature race was won by Bob Barnett driving last season’s MG TD-Corvette, fending off Charles Bettman’s VW-Porsche Special. In the next race at Plainville Stadium, Bettman took his revenge by winning the feature ahead of Barnett, but Barnett came back strongly to win at Riverhead Raceway and Williams Grove Speedway.

SCODA’s inaugural race meeting at Danbury attracted at least 27 entrants and a crowd of over 3,000 spectators. A new name appeared on the winner’s step of the podium, Charles Blewett, who drove his Ford Thunderbird to victory ahead of Charles Bettman. It was also the first victory of the season for Pete Mourad when he drove his Jaguar XK120 Special to victory at Wall Stadium in July.

The decision was made by the SCODA Board of Directors to revert the car class split to 1500cc for the 1959 season, as it would appear that nothing had been gained in changing the format for 1958. It was also announced that there would be at least 18 proposed events taking place throughout the season, including four in the Mid-Atlantic states. As the season progressed, the number of events dwindled due to bad weather with Islip, Polo Grounds Speedway, and Fonda venues as three early victims.

Some members from SCODA attended an early season event at Langhorne Speedway, no doubt enticed by the $5,000 purse for the feature race. Bob Barnett took fourth place, a creditable performance against the likes of Carroll Shelby in a Cadillac Special, Loyal Katskee in a Ferrari, and Bob Brown in a Jaguar 3.4 Special.

A meeting at McLean County Raceway, Smethport was won by Walt Hennigar in his Corvette-powered Austin-Healey in late May, while Bob Barnett drove his well-used MG TD-Corvette to victory at Empire Stadium Raceway on June 11. Of the other known results for the 1959 season, Bettman won at Fonda in June, using a Porsche 550 RS Spyder in place of his VW-Porsche Special, and Bill Boyd completed a narrow victory in his Miller-Corvette Special over Bob Barnett at Plainville. In taking the second spot, Barnett accumulated enough points to become the new SCODA champion for 1959, the first championship he had won.

The 1960 season was the last where any race details were reported on in the press on anything approaching a regular basis. A further change in club regulations saw the establishment of a new racing formula to encourage production autos to be involved in the races. Four divisions had been made, large and small production models, and large and small modified versions.

The first meeting of the season was held at Seekonk Speedway, a one-third-mile semi-banked paved oval that had been operated by the Venditti family since its opening in 1946. After winning his 10-lap heat, Fred Luchesi went on to win the feature race finishing ahead of Barnett and Boyd. A trip to Old Dominion Speedway followed, where Bob Barnett claimed the honors ahead of Bill Boyd. The Fonda Speedway races were postponed from Saturday, May 28 until the following Monday night due to heavy rain. Boyd turned the tables on Barnett to take the victory. SCODA did turn up at Lincoln Speedway for the first time in July where Lynn Connor, driving a Jaguar Special, won the feature race ahead of Barnett, and Herb Fisher beat Bill Boyd at a meeting held at Fonda in July.

An appearance at Thompson Speedway was due, but no evidence of the event taking place was found. The second half of the season was chaotic, meetings at Old Bridge, Arlington Speedway, Westboro Speedway, and West Peabody Speedway were supposed to take place, though no reports or results came to light.

At the end of the 1960 season, SCODA had more or less automatically dissolved its activity. President Bob Barnett indicated that the unwieldy board of directors had seriously hampered the club’s operations. Rather than dissolve the club entirely, the board of directors had been dissolved and it was left to Barnett to re-organize operations on a more realistic basis. In 1961 there would be no SCODA representation at the oval tracks.

A limited race program did recommence in 1962 with meetings at Old Bridge Speedway (won by Ken Andrews in a Jaguar twice in the season), Wall Stadium, and Plainville Speedway taking place, and a meeting at Old Dominion Speedway having to be canceled due to persistent rain.

There were two possible reasons why information was difficult to come by in the following years. First, with a lack of club directors, too much pressure was applied on Bob Barnett in the early 1960s and his failure to communicate with the press or place adverts for the races led to an information blackout. Second, the press had lost interest in SCODA because its race program appeared to diminish. Either way, it was not a true representation of the facts as the scant information available would suggest. Large numbers of entries and races at the established venues for SCODA continued certainly up to 1969. Reports that the following drivers took place in competition are confirmed in the drivers standings for 1964: Steve Krisiloff was top, followed by Ken Andrews, Jack Bettio, Dan Brent, Warren Arhens, Ron Russo Jack Van Wettering, Bob Wagner, and Hans Kleban. From reading these names it was also obvious that the old guard of drivers had either taken a back seat or disappeared from the scene and a new batch of drivers had taken their place.

In 1965, Al Krisiloff was elected as president of SCODA, and the class structure was changed yet again. That year Al Loquasto was the Class A top driver in his Chevrolet Corvette Stingray ahead of Art Kijek driving an Austin-Healey Corvette, while Andy Swain headed Class B and Bill Claren Class C. Loquasto won races at Hagerstown Raceway, Lincoln Speedway, Catamount Speedway, and Evergreen Speedway. Towards the latter half of the season, the weather wreaked havoc on the race schedule. The meetings at Milton Speedway, Pocono, and Pine Bowl Speedway were all canceled.

So far as can be confirmed, there were SCODA races held at Albany-Saratoga Speedway, Williams Grove Speedway (twice), and Richmond State Fairgrounds during 1966, but details are sparse. Steve Krisiloff won at Albany and Al Loquasto took the victory at Richmond. Other races would have taken place during the season – Steve Krisiloff won the championship by 10 points from John Paschal.

There was more reported activity (albeit scant) for 1967. At the start of the season, races were scheduled for Hershey, Pennsylvania, Thompson Speedway, Connecticut, Berwick Beach, Pennsylvania, Airborne Park, New York, Stafford Springs, Connecticut, Orange County Fairgrounds, New York, Atlantic City Speedway, New Jersey, Nazareth, Pennsylvania, and Catamount, Vermont. However, a few changes were made as the season progressed, with known races taking place at Westboro Speedway, Plainville, Williams Grove, and Fonda.

Joe Paschal ended up as the top driver for the season with 1100 points, 190 more than second-place finisher, Fred Pfisterer, one of the founder members of SCODA. Paschal drove his Chevrolet Corvette Stingray to victories at Hershey, Nazareth, Westboro, and Stafford Springs, while Steve Krisiloff in his Austin-Healey-Corvette won at Fonda, Atlantic City, and Williams Grove.

According to a report printed in the Illustrated Speedway News, SCODA was inactive during the 1968 season, although it appears that several SCODA drivers did participate in races sanctioned by other organizations. Fred Luchesi and Bob Barnett appeared at Seekonk, and Barnett and Boyd at Atco Speedway, while Al and Ben Loquasto were entered at Harmony Speedway.

At the 1969 AGM, Bill Claren stepped down as president, his place being taken by Nick Caviluzzi, a long-time member and official of the club.

A number of race meetings did take place, including ones at Westboro Speedway (twice), won by Jerry Walsh in an Austin-Healey-Corvette and Mike Dee in a Chevrolet Corvette Stingray, Harmony Speedway where Joe Hesse claimed victory and Atlantic City Speedway, won by Woodie Bimm.

Beyond the end of 1969, no accounts of races were found, and no reports about SCODA club activities came to light. It is possible that SCODA ceased to function.

Should any reader have further information about SCODA I would be pleased to hear from them.

While people more readily associate American race drivers as appearing in Europe after World War II, it is worth reflecting on one individual, who through circumstances that were not of his own making, took up the mantle in the 1930s.

This was Whitney Willard Straight, born in November 1912 in New York. His parents had wealth beyond the dreams of most people, an asset that Whitney put to use in setting up his own race career as well as his own company. His father died of Spanish Flu, and his mother, an heiress in her own right, remarried agronomist Leonard Elmhurst. In 1925, the family moved from America to Darlington House in Devon, England. The young Whitney attended the progressive school that his parents had founded before going to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied philosophy.

This was Whitney Willard Straight, born in November 1912 in New York. His parents had wealth beyond the dreams of most people, an asset that Whitney put to use in setting up his own race career as well as his own company. His father died of Spanish Flu, and his mother, an heiress in her own right, remarried agronomist Leonard Elmhurst. In 1925, the family moved from America to Darlington House in Devon, England. The young Whitney attended the progressive school that his parents had founded before going to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied philosophy.

While at Trinity College his thoughts turned to motor sport and he purchased his first car, an Alvis Silver Eagle. He did not race this car, but purchased a second vehicle, a Riley Nine (more commonly referred to as a Brooklands Riley), and it was this car that he entered at Shelsley Walsh, his first competitive event, in July 1931. Straight finished in third place in his class behind two other Rileys. It was here that he became aware of Dick Seaman who was attending Trinity College, and was also racing a Riley. Straight and Seaman were to become very close friends over the coming months.

Three more meetings were attended before the end of 1931, two at Brooklands and one at Southport. In each of these races, he finished well up in the classification but realized that he needed something more powerful if he was to really compete for honors.

His first race of 1932 was to see him travel to Sweden for the Swedish Winter Grand Prix, the only foreign racer to make the journey. He was embarking on an extensive program of racing that would occupy him fully over the next few years. The circuit was huge, nearly 30 miles over frozen roads in an area near Lake Rämen to the west of Stockholm, which the drivers had to cover eight times. Straight soon had trouble and was well behind after two laps, at which point he decided to drop out of the race.

Straight purchased a 2-liter non-super-charged GP Bugatti which he used at Brooklands. He came in first overall on a handicap basis, but was still not satisfied. As a result, Straight bought the ex-Birkin 1931 2.5-liter Maserati and used it in the two remaining races of the season that he had entered. He finished in the second spot in the Lightning Mountain Handicap losing out by one-tenth of a second, in what was described by motoring correspondents as one of the most exciting Mountain races ever.

1933 proved to be a busy year for Straight. As well as attending eight meetings in England, he was present at Rheims, Stockholm, Pescara, Comminges, Albi, Mont Ventoux and Monza. There were victories at Brooklands, Brighton, Nottingham, Shelsley Walsh and Mont Ventoux in the Maserati M26 as well as a victory in the 1100cc race in Pescara in an MG K3 Magnette. In the main event at Stockholm he drove Bernard Rubin’s 2.6-liter Alfa Romeo, before flying himself and his mechanic Berk Harris to Pescara in his own airplane. Mont Ventoux was the highlight of his season when the Maserati 26M broke the track record with a time of 14min 31.6 sec, taking no less than 40 seconds off Rudi Caracciola’s previous figure in a Tipo B Alfa Romeo.

The MG K3 Magnette was also driven to victory in a squall of rain at Brighton by Psyche Altham, and entered a hillclimb at Shelsley Walsh. She did not record a time due to a problem with the MG’s carburetor, but Psyche also raced the car at Brooklands finishing third in the Ladies’ Mountain Handicap race. After the 1933 season she disappeared from the motorsport scene. (It was reported in one motoring magazine that she was Straight’s fiancee, but in 1935 he married Lady Daphne Margarita Finch-Hatton.)

The latter half of 1933 was to witness some interesting developments for Whitney Straight, as he decided not to remain at Cambridge for his third year of studies but to take up racing more professionally.

He moved from Cambridge to London to form Whitney Straight Limited, and the Company was registered in December with a nominal capital of £5000, the directors being Whitney Straight, Reid Railton, and William Lambert. Having done that, he wanted to increase the number of cars to race and was interested in purchasing three Alfa Romeo Tipo B monopostos. However, Alfa Romeo could not supply the cars so Straight went to their rivals and ordered three of the latest 2.6-liter 240 bhp 8CM Maseratis which cost him £6,000. Giuilio Ramponi was appointed head mechanic and three trucks were obtained to transport the racing cars. Hugh Hamilton and Buddy Featherstonhaugh were contracted to drive the cars along with Whitney Straight for the 1934 season.

It turned out to be a season of mixed fortunes, starting well with a win at Brooklands by Straight in a Maserati 8CM, though come two weeks later both of the Whitney Straight entries retired from the race at Tripoli. Casablanca was an improvement with Straight taking fourth place but Hamilton went out on lap 42.

It wasn’t until the Albi Grand Prix on July 22 that the Whitney Straight team was to savor success again, with Hamilton winning in the Maserati 8CM and Featherstonhaugh coming second in the well-used Maserati 26M. This meeting was followed up at Klausen with a win for Hamilton in the under 1100cc race in the MG K3 Magnette, and again at Pescara two weeks later. A win at the Berne race on August 26 by Dick Seaman in the MG K3 Magnette was poor consolation for the tragic accident that happened in the Swiss Grand Prix when Hugh Hamilton was killed driving a team Maserati 8CM car, crashing into a tree on the final lap of the race. The accident put a dampener on the remainder of the season, though there was one last flourish at the South African Grand Prix when Whitney Straight brought his Maserati 8CM home in first place.

It was a fitting end to the season, and a fitting end to Whitney Straight Limited, as Straight had decided to retire from motor racing. One of two reasons was that the decision was undoubtedly influenced by the untimely death of Hugh Hamilton, and secondly, Straight had found to his cost that racing was a very expensive hobby. At the end of the 1934 season, all things taken into account, Whitney Straight Company had lost £2,775. Wealthy though Whitney was, he realized that to continue into another season would be unsustainable.

In a bygone era on the African continent, when most southern African countries were colonies under the control of European powers, “Grand Prix” motor racing for sports cars flourished for a brief period of time.

One such country involved was Angola, a Portuguese colony, and it was the Portuguese government that encouraged this action as it wanted to expand motorsport in order to build a sense of unity in its empire at a time when there were signs of unrest.

There was already thriving local motorsport in the capital of Luanda and some of the provinces. The main organization representing the sport was the Automovel e Touring Clube de Angola, with many monied members mainly connected to the tobacco and oil industries. The president of the club, Acacio Pereira de Matos, regarded as a faithful representative of motorsport in Angola, was given the responsibility of organizing the event. His position as a member of the colonial bourgeoisie and from an old family in the province linked to Norton de Matos, governor-general of Angola, stood him in good stead for the task ahead.

There was already thriving local motorsport in the capital of Luanda and some of the provinces. The main organization representing the sport was the Automovel e Touring Clube de Angola, with many monied members mainly connected to the tobacco and oil industries. The president of the club, Acacio Pereira de Matos, regarded as a faithful representative of motorsport in Angola, was given the responsibility of organizing the event. His position as a member of the colonial bourgeoisie and from an old family in the province linked to Norton de Matos, governor-general of Angola, stood him in good stead for the task ahead.

Following the example set in the Belgian Congo the previous year, the motor race was arranged to be run on a street course that measured 3.429 Km and wound its way around the streets of Luanda. It was known as the Fortaleza Circuit, with the main straight going along the Avenida Marginal.

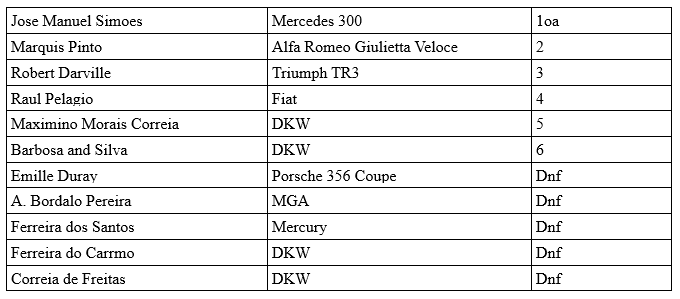

To run in conjunction with the Grand Prix, a second race was established for mainly local drivers with cars of lesser power. This race, known as the Taca Cidade was held the day prior to the Grand Prix and produced a field of eleven cars. The race distance was substantially shorter than the Grand Prix and was won by the Portuguese driver Jose Manuel Simoes driving a Mercedes ahead of Marquis Pinto and Robert Darville. Unfortunately, the event was not covered in any depth by the newspapers in Angola, and subsequently, some information is vague.  Entries for the Grand Prix race were received from Portugal, South Africa, Mozambique, Kenya, and Belgian Congo, as well as a couple of local drivers from Angola.

Entries for the Grand Prix race were received from Portugal, South Africa, Mozambique, Kenya, and Belgian Congo, as well as a couple of local drivers from Angola.

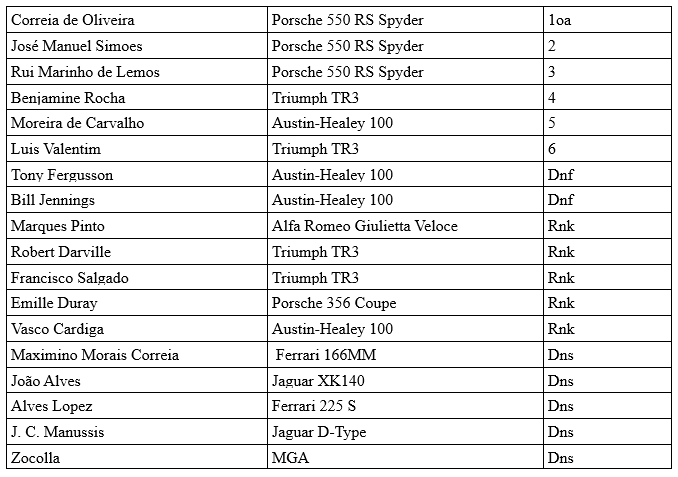

The better-known and more established drivers turned up with Porsche 550 Spyders, transported from Portugal by TAP airline, while Austin-Healey and Triumph TRs were the choice of most other drivers. There were two Ferraris transported to Luanda from Portugal, purchased by the ATCA for the use of the two outstanding Angolan drivers, Maximino Morais Correia and Alves Lopez. The Ferrari 166MM and 225 S models had been raced in Portugal in the early 1950s but since then had languished in a garage, so were not in the best of condition to be put through their paces again.

As far as can be established, eighteen cars were entered for the race – though only 13 starters can be accounted for. One driver, J. C. Manussis from Kenya, had an accident on his way to Luanda in the truck carrying his Jaguar D-Type and was forced to return home.

As far as can be established, eighteen cars were entered for the race – though only 13 starters can be accounted for. One driver, J. C. Manussis from Kenya, had an accident on his way to Luanda in the truck carrying his Jaguar D-Type and was forced to return home.

Practice for the Grand Prix was started on Friday at 7:00 a.m. for an hour, so as not to interfere with local business. The roads closed at mid-day for the Taca Cidade race. Within the practice time allocated, the two Ferraris were side-lined with mechanical issues, and with few spare parts and no trained Ferrari mechanics, the cars were withdrawn from the race. Likewise, both João Alves and Zocollo suffered malfunctions with their cars and failed to make the starting grid.

Portuguese driver Correira De Oliveira placed his Porsche on pole and pulled into the lead, a position he maintained until the end of the 70-lap race. Followed closely by Simoes for the first half of the race before he eased up when it became obvious to him that he could not pass, Oliveira contented himself with second place at the finish. Lemos, a navigator on TAP aircraft and part-time driver finished in the third spot. South African driver Tony Fergusson in his Austin-Healey had held the third spot but had to retire on lap 33.

One potentially serious accident happened in the race when South African Bill Jennings, driving an Austin-Healey, skidded and climbed the curb, plowing into a pile of hay bales. Luckily for him, track marshals were on hand to rescue him. Despite the swift action of the marshals, Jennings was hospitalized for a week in Luanda to recover from his injuries. Even though he failed to finish due to his accident the race officials classified him as finishing in seventh place, based on the distance covered.

One potentially serious accident happened in the race when South African Bill Jennings, driving an Austin-Healey, skidded and climbed the curb, plowing into a pile of hay bales. Luckily for him, track marshals were on hand to rescue him. Despite the swift action of the marshals, Jennings was hospitalized for a week in Luanda to recover from his injuries. Even though he failed to finish due to his accident the race officials classified him as finishing in seventh place, based on the distance covered.