The following is an excerpt from the book, IMSA: 1969-1989, by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Once IMSA was incorporated in the summer of 1969, founder and president John Bishop turned his attention towards figuring out what kind of show the fledgling sanctioning body was going to produce. Bishop was committed to not competing with the SCCA, whose professional racing championships were dominating the racing scene; the Trans-Am and Can-Am series were arguably at the peak of their popularity. He decided to run a series of races for Formula Fords and Formula Vees on ovals, along with a few road courses. There were plenty of cars available and no professional outlet for these drivers. And key tracks were owned by benefactor Bill France, Sr. Calls were made to promoters and the first few races were scheduled.

Invitations were sent to all the top open-wheel drivers to join IMSA and come race. The immediate and positive response from drivers were encouraging and gratifying. Bishop’s name and reputation, carefully built during his tenure at the SCCA, was opening doors. The fact that IMSA was offering prize money didn’t hurt, either.

The first IMSA race was scheduled for October of 1969, a Formula Ford event on the short, 5/8-mile oval at Pocono International Raceway. A promoter’s agreement was signed, entry forms were mailed out and the race was advertised in the trade press. The entry list started building to an eventual 23 drivers and cars. Everything was going smoothly, or so it seemed.

Just two weeks before the inaugural IMSA event at Pocono, John Bishop received an urgent call from Dave Montgomery, the track president, who told him that he was going to have to cancel the race due to pressure from the SCCA. The Club was threatening tracks and workers with ex-communication if they participated in any IMSA events, a tactic borrowed from the early days of the road racing wars in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Although it was barely off the ground, the Club viewed IMSA as a potential rival. Ultimately, this approach didn’t work and was abandoned, but the short-term threat to IMSA was quite real. Track owner Joe Mattioli did agree to lease the track directly to IMSA but could not agree to do more for fear of losing SCCA dates the following year.

Deciding that IMSA’s credibility was on the line, Bishop swallowed hard, borrowed $10,000 to lease the track and solidify the prize money. He scrambled and called on friends to help with timing, scoring, pit marshal duties, technical inspection, and safety roles. The race was back on. Inverhouse Scotch came on board at the last minute to help with prize money and promotion.

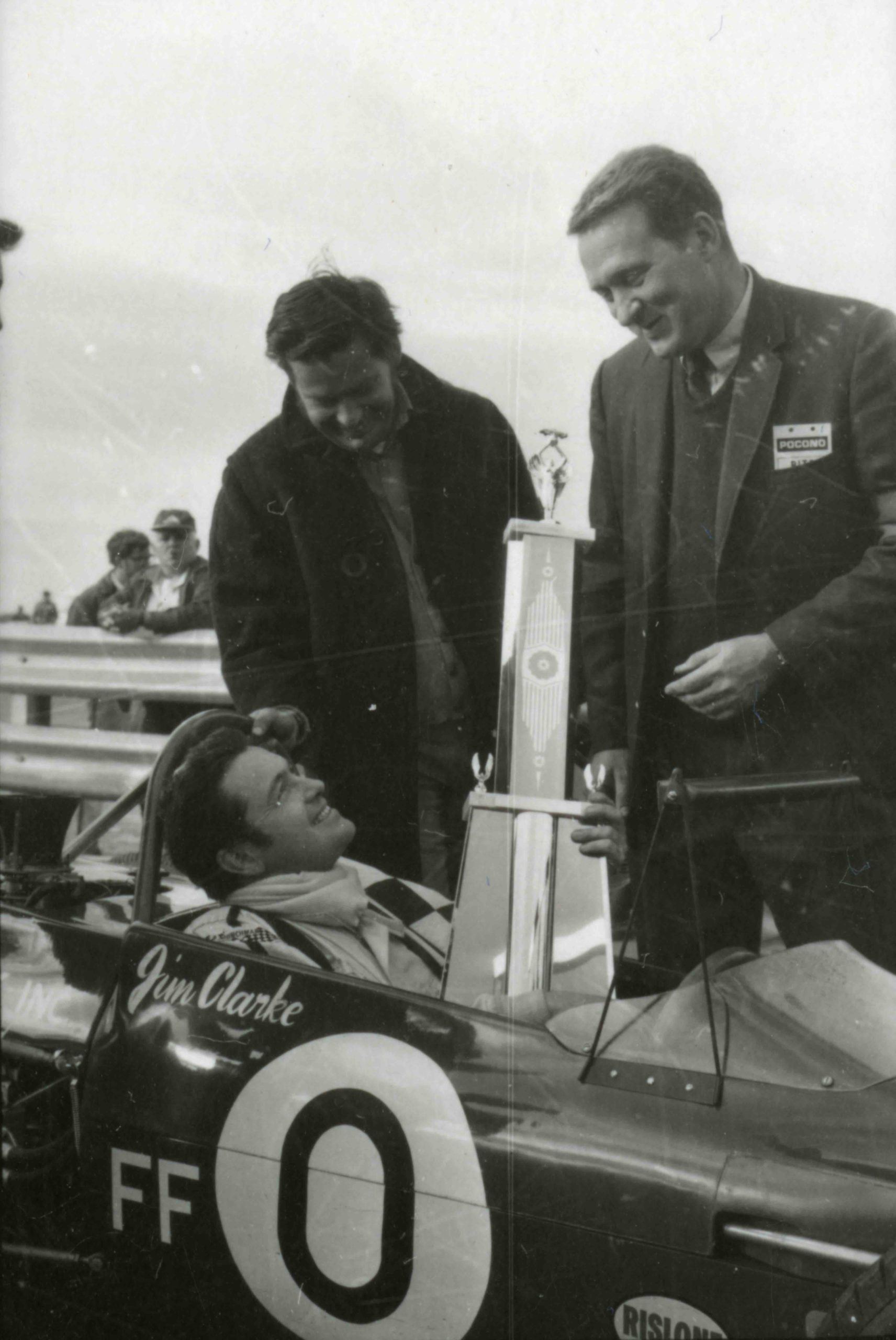

NASCAR founder and original IMSA investor Bill France Sr. and John Bishop enjoy a laugh before the race at Pocono. Dick Gilmartin, IMSA’s first public relations director, is on the left. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

On October 19, 1969, the 23 teams that showed up were immediately treated to some refreshing changes from the way things were done at the SCCA. There were apples and friendly faces at registration, and prize money was awarded to everyone that started. Ray Heppenstall helped Charlie Rainville with technical inspection and they introduced another innovation; teams didn’t have to line up. Instead, Ray and Charlie went around to where the competitors were parked in the infield and did their work on the spot. It was a revelation to competitors.

Promotion for the event had appeared in Competition Press & Autoweek, but very little marketing had been done locally. Still, 350 curious spectators showed up. Everyone in the Bishop family pitched in. Peggy ran registration and worked scoring. Son Marc, on leave from the Navy, along with John’s brother Peter, sold tickets. Sons Marshal and Mitch directed traffic in the parking lot and worked timing and scoring. Drivers’ wives were also pressed into service to score the race. It was an “all-hands-on-deck” exercise. Bill France Sr. made sure to lend his support by flying in, giving the event instant legitimacy.

A rare shot of the driver’s meeting for the inaugural IMSA race at Pocono. Bill France Sr. is on the far left, wearing the hat and long coat. Jim Jenkins in on the left, in front of the window. Bill Scott talks with Carson Baird in the foreground. John Bishop is by the tow truck in the back. Fourth from the right is Don Nixon, who ran timing and scoring for the event with his wife Ruth. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

Some of the best Formula Ford drivers of the day showed up: Skip Barber, Bill Scott, Jim Jenkins, and Fred Opert, among others. Almost all of them had no experience on ovals and many guessed at the proper setup. One of the guys that guessed wrong was George Alderman, an experienced SCCA racer who backed his car hard into the outside retaining wall during qualifying, ending up in the hospital overnight with a concussion. The car was not so lucky, it took months to rebuild. Alderman came back to become an IMSA regular and won the 1971 and 1974 IMSA RS series titles.

The race itself was a 200-lap affair. The pace was frantic on the flat, 5/8-mile oval. Timing and scoring was being done from the grandstands; there was no covered area to work. The scorers, used to longer road courses, were overwhelmed by cars completing laps in just 26 seconds. It was all done the old-fashioned way – by hand.

Winner Jim Clarke receives congratulations from the IMSA founder following the first race at Pocono. It wasn’t until after the trophies and prize money were handed out that a scoring error was discovered. It was never corrected. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research

At the end of the race, Jim Clarke was declared the winner, and a modest Victory Lane ceremony was held. Post-race analysis, however, revealed that an error had been made and the second-place driver, Jim Jenkins, had actually won. But the ceremonies were over, the spectators were long gone and teams were packing up to go home. Bishop decided to let the results stand. They were never corrected.

“Don and Ruth Nixon were running timing and scoring for us that race,” Bishop recalled. “The rest of the scoring team was largely made up of drivers’ wives. When Carson Baird crashed on lap 31, his wife Betsy stood up and screamed. Peggy told her to sit down and keep scoring. Somehow, we missed the real winner. Jim Jenkins should have won the race but instead, the win was given to Jim Clarke. I remember Don Nixon running down the grandstand shouting, “Don’t give out the checks!” but by then it was too late.”

After all the drama and hard work, IMSA had pulled off its first race. Yes, the crowd was small and there were issues, but the sanctioning body was now off and running.

Just two months later, IMSA held three races at the newly built Alabama International International Speedway (Talladega), one each for Formula Vees and Formula Fords, and one for a new class called International Sedans. For the first time, they used the four-mile combination oval/road course, even though Bishop was beginning to get concerned about the safety of running open-wheel formula cars on ovals. “Race cars have to be faster than the track,” he pointed out. “If the track is faster than the cars, then you have the potential for big trouble. We learned that the hard way with Formula Fords at Charlotte the next year.” Race day was not a commercial success; the 500 spectators were completely lost in the grandstands designed to hold thousands of rabid NASCAR fans.

The 1970 season was largely focused on running more formula car races on a mixture of ovals and road courses, starting with season-opening events at Daytona in February during Speed Weeks. The Formula Vee race had just twenty entries but paid the winner Bill Scott more than $5,000, a princely sum at the time. A week later, IMSA put just 15 Formula Fords on the grid at Daytona. Both races were run on the combined oval and infield road course.

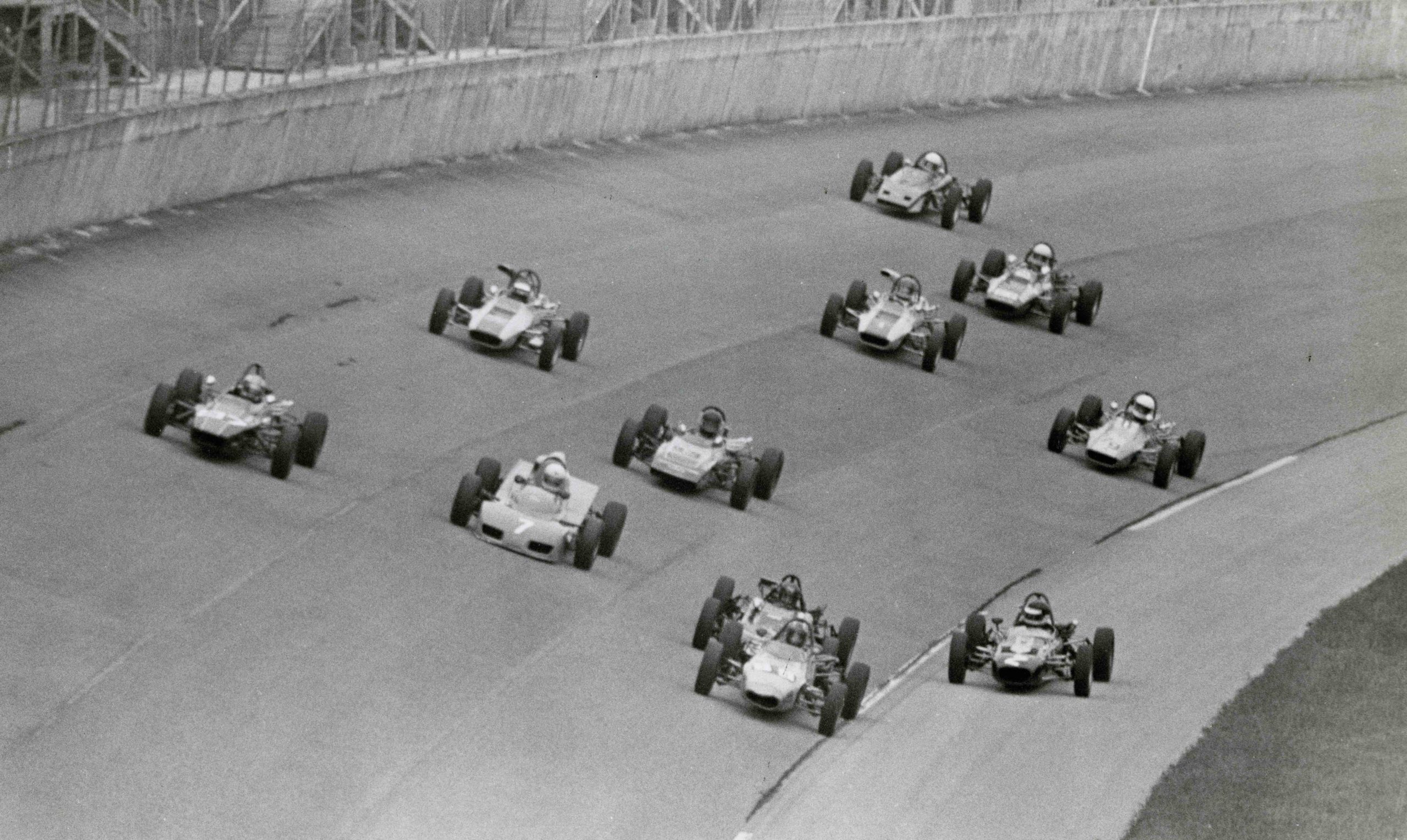

Putting a bunch of Formula Fords on the wide-open expanses of Alabama International Speedway (Talladega) was a recipe for exciting pack racing but also an invitation to disaster. Photo: Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research

Thirty-Three Formula Fords showed up for the next race in April at Talladega. Again, the drafting and dicing on the oval section was spectacular, but with more cars on the track the inevitable happened; there were multi-car wrecks in the first heat that damaged 13 cars badly enough they were unable to start the second heat. Fortunately, no one was seriously hurt but John Bishop was shaken by the close calls. IMSA was barely limping along; somehow IMSA had dodged a bullet.

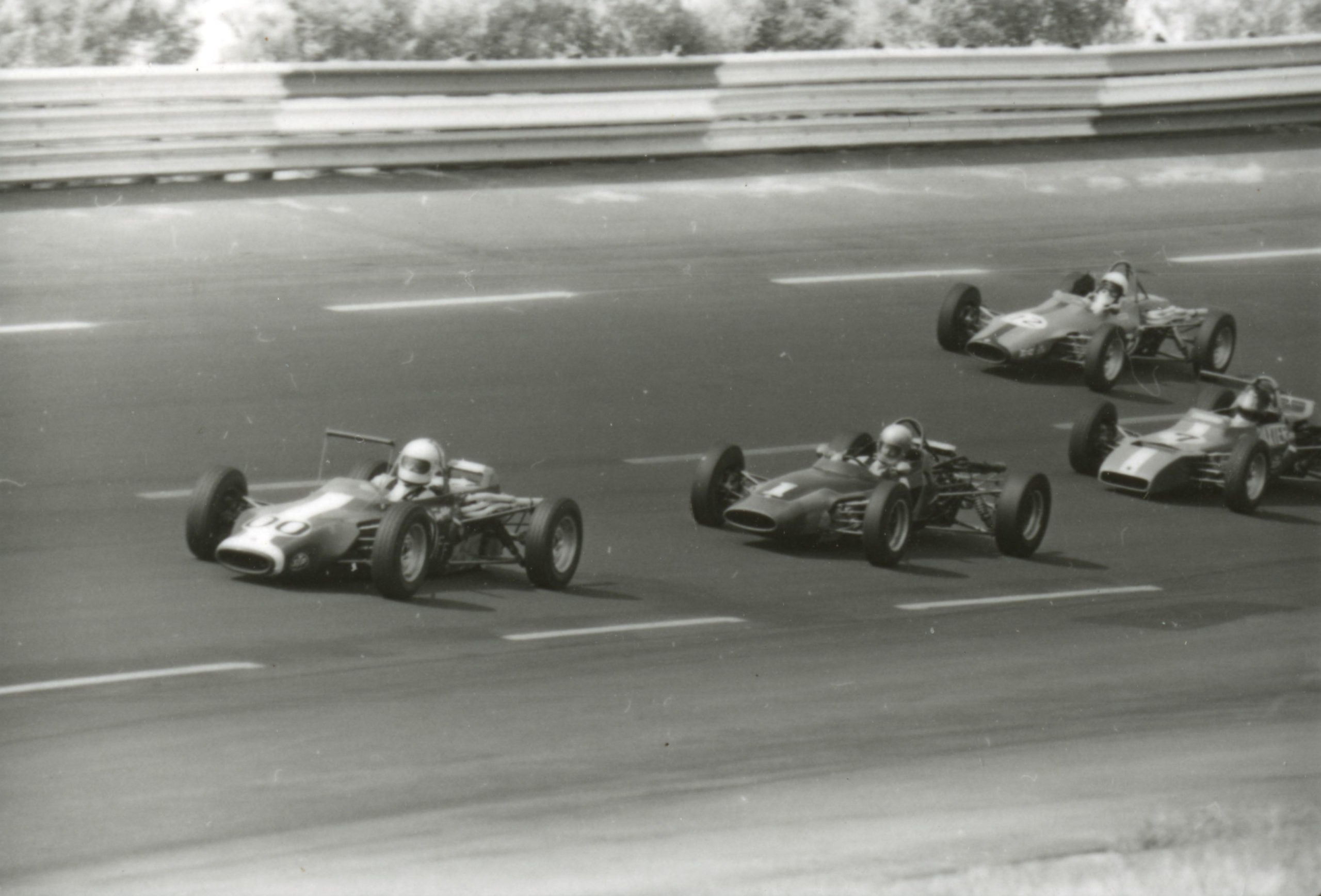

Early laps of the Formula Ford race held on the full oval at Charlotte Motor Speedway in May 1970. Gary Weber in No. 00 leads Vic Matthews in No. 1 prior to a dangerous wreck. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

The race at Charlotte Motor Speedway in May was the turning point. Run on the full 1.5-mile oval, the field of 22 Formula Fords ran in a tight pack the entire first heat, drivers drafting each other within inches of one another. No one could break away from the bunch. Passing required staying in the draft, tight on the tail of the car in front, gaining momentum and then dodging right or left out of the slipstream. Entering the front straight, the leading pack of six cars came together in a spectacular crash. After touching wheels, Vic Matthew’s Macon flipped end-over-end, as did the car of John Kinney. Bob Gardner ended up in the wall. The declared winner of the first race at Pocono, Jim Clarke, ended up underneath Spurgeon May’s Caldwell, effectively trapping Clarke in the car. After coming to a halt on the grass, the stack of two cars burst into flames. Spurgeon climbed out but Clarke was wedged in his car, unable to exit.

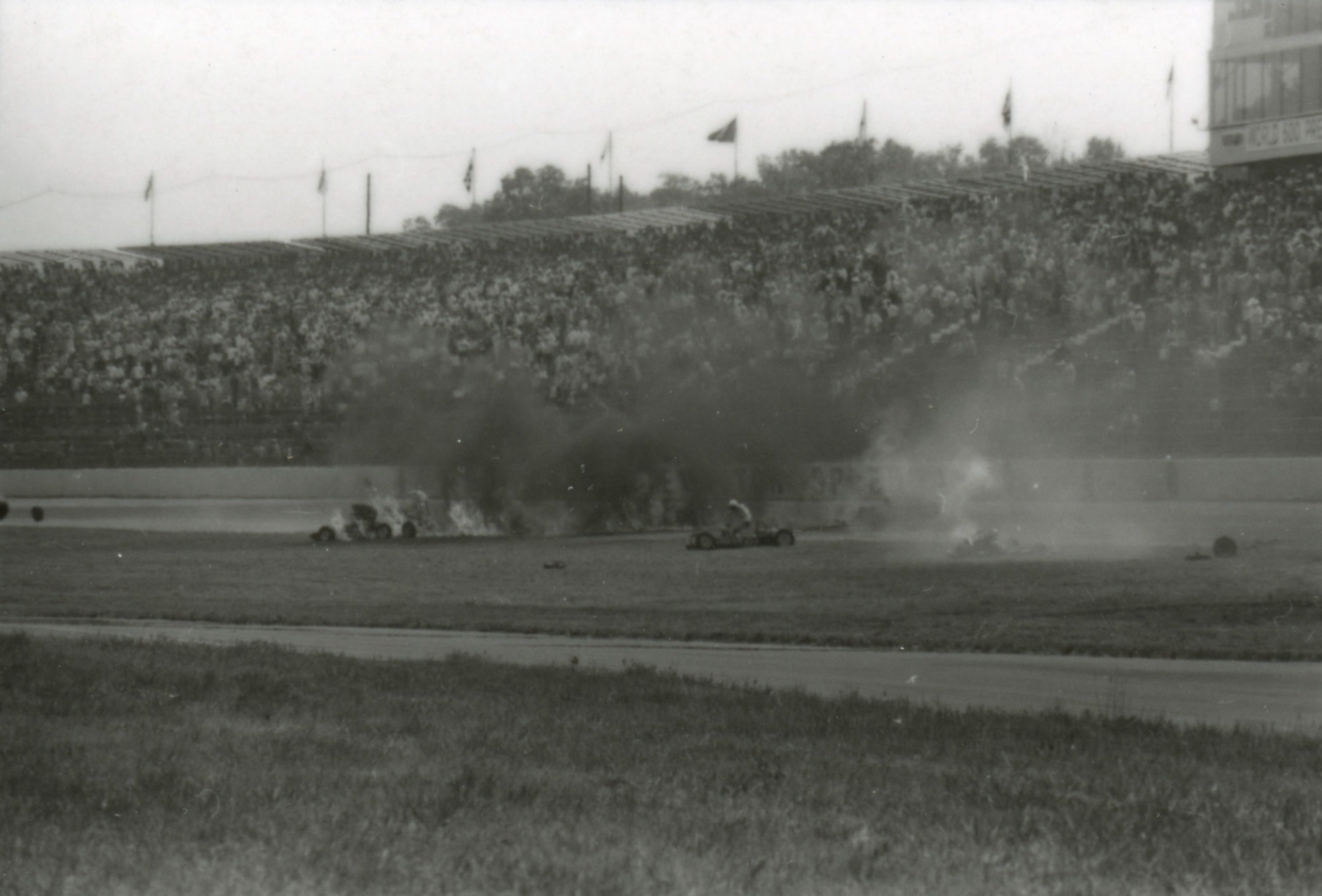

A very rare sequence of shots of the huge wreck at the IMSA Formula Ford race at Charlotte in May 1970. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

Spurgeon May pushes his car out of the way after the Charlotte crash. His Caldwell Formula Ford came to rest on top of Jim Clarke’s machine before both cars were engulfed by flames. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

As Clarke later recalled; “After the initial impact, when we came to a stop, I remember thinking that I was lucky to be unhurt. Then, I smelled gasoline and thought to myself: I need to get out of here! After we caught fire, my next thought was: well, this is it, there’s no way out, I’m going to die. I resigned myself to my fate. Then it started to get really hot and I thought: The heck with this, I’m getting out of here! And I did something no one thought possible; I punched a hole in the side of the fiberglass bodywork with my fist and crawled out.”

The race was red-flagged and never restarted. Kinney and Matthews were both hospitalized with head, ankle, and burn injuries. A total of eight cars were damaged beyond repair in time for the second heat run later that day, which was shortened due to safety concerns. No one was killed in the melee and the injured recovered. But once again, IMSA had just barely dodged a bullet.

IMSA was struggling. Beyond the safety issues, not enough people were coming out to see the races. The company was in the red and had to borrow more money to stay afloat. It was time for a new vision. Bishop wrote an entirely new rule book in the fall of 1970 for the following season with the help of Charlie Rainville and input from some of the key drivers of the day like John Greenwood and Peter Gregg. That winter, the rule book was widely distributed to SCCA racers who had already built FIA Group 2 and Group 4 cars but didn’t have a place to race them professionally other than the annual endurance events at Daytona, Sebring and Watkins Glen. Reaction was positive, both from competitors and track promoters. Jim Haynes at Lime Rock and Les Griebling at Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course both signed on right away, as did the folks at Bridgehampton Race Circuit.

The new IMSA GT series debuted in April 1971 at Virgina International Raceway. It was an instant success with promoters, drivers, team owners and sponsors. Camel cigarettes joined as the series sponsor at the end of 1971 and starting in 1972, the Camel GT Series quickly became the most popular professional sports car racing series in the world.

Yes I was very lucky that day in May…

I remember several seconds of a formula ford sliding along an oval upside down–on the national evening news! and the good ol’ scca: a combination of the ‘pharaohs of Westport’ and the phone company…

I was crew for one of the cars in the race. Standing on the pit wall when the wreck came to a stop across from me.

There was a multi-car wreck on the west end of Talladega on Saturday,and I recall looking to my left, and seeing Scott Schilling upside down about 6 feet in the air. The next day it was my turn to eat cement. Scott was killed on the Florida Turnpike on his way home from that freaky race. He and his pal “Skeeter” were both killed.

I drove Caldwell#88 for Competition Technology from Miami, Fl. I had a 4th, and then came out 2nd at VIR I-100 class behind David Loring. I ate the wall on the third turn at Talladega missing a t-bone with Dave Yoder, this at full speed! Ouch!! Bristol was cancelled due to weather,and we had a flat tire at the Daytona 200 for the I-100 Class that year. I-100 seems to have disappeared from all IMSA history.It was very close racing between several SCCA National, and Regional champions.