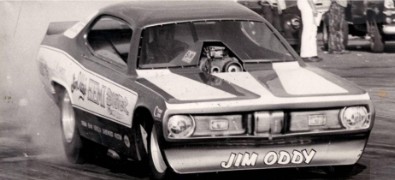

Niagara Dragway was one of the most popular and iconic drag strips in New York State from the early 1960’s to 1974. “SUNDAY…NIAGARA” commercials boomed from superstation WKBW during that period making Niagara THE PLACE TO BE for maximum automotive excitement! “Straight Line Speed – the History of Niagara Dragway” will be the topic of the IMRRC’s first Center Conversation series of the season, on Saturday. May 10 from 1-3PM. Track promoter, Dean Johnson and Jim Oddy, a long time competitor at the track and a member of both the NHRA Division 1 and the International Drag Racing Hall of Fame will be our guests. During its time, the icons of the sport – Garlits, Muldowney, Prudhomme, McEwen, and many others rocketed down the quarter-mile. We’ll relive that history with stories, photos, and memories of those wild years. On display in the Center is an awesome 1963 AA/Top Fuel dragster built by ‘TV’ Tommy Ivo and campaigned by 3 guys from Brooklyn known as the “Dead End Kids” We’re also inviting hot rod and car clubs from around the state to attend and showcase their cars in the school’s parking lot

So, make plans to make a “Straight Line” to the IMRRC on May 10! For more information and details, please contact Kip Zeiter at (607) 535-9044 or email at: kip@racingarchives.org

In celebration of 60 years of TransAM racing, and the inaugural class of Hall of Famers at Sebring in 2025; we wanted to take you back to 2015 when the IMRRC hosted a panel of notable figures in TransAm’s history. Folks like Chuck Cantwell, Lee Dykstra, Don Cox, John ‘Woody’ Woodard, Tommy Kendall, Butch Leitzinger were hosted by Judy Stropus – recapping the first 50 years of the series.

This panel covers the history and development of Trans Am racing, their personal experiences, stories of innovation and trickery in racing, and the evolution of race car technology. They also reflect on memorable races, provide insights into their careers, and discuss the competitive spirit and changes in this unique variant of Road Racing. Featuring a live audience Q&A, they also touch upon the current state of Trans Am compared to its earlier days.

Highlights

- 00:00 Celebrating 60 Years of Trans Am Racing

- 01:07 Panel Introduction; Judy Stropas Takes the Stage

- 07:35 Chuck Cantwell’s Early Trans Am Days

- 11:14 Lee Dykstra’s Contributions to Trans Am

- 14:03 Don Cox’s Chevrolet Insights

- 20:04 John Woodard’s Penske Racing Journey

- 25:33 Butch Leitzinger’s Trans Am Experience

- 27:39 Tommy Kendall’s Racing Legacy

- 35:55 Stories of Innovation and Trickery

- 47:49 The Controversy of Traction Control

- 53:55 Balance of Performance

- 56:01 Roger Penske’s Winning Strategy

- 58:35 Historic Trans Am Cars and Their Legacy

- 01:05:51 Conclusion and Audience Q&A

- 01:20:27 The Future of Racing: Innovation vs. Regulation

This episode is part of our HISTORY OF MOTORSPORTS SERIES and is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] Brake Fix’s History of Motorsports series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argettsinger family.

Crew Chief Eric: In celebration of 60 years of Trans Am racing and the inaugural class of Hall of Famers at Sebring in 2025, we wanted to take you back to 2015 when the IMRRC hosted a panel of notable figures in Trans Am’s history.

Folks like Chuck Cantwell, Lee Dykstra, Don Cox, John Woody Woodard, Tommy Kendall, Butch Leitzinger, were all hosted by Judy Stropas for a recap of the first 50 years of the Trans Am series. This panel covers the history and development of Trans Am racing, personal experiences, stories of innovation and trickery in racing, and the evolution of race car technology.

The panel also reflects on memorable races, providing insights into their careers, and they discuss the competitive spirit and changes in this unique variant of road racing. [00:01:00] Featuring a live audience Q& A, they also touch upon the current state of Trans Am compared to its earlier days.

IMRRC: My name is Tom William, and if I haven’t had a chance to meet all of you, and I can’t tell you how delighted we are to have you all here, and have this wonderful panel here today.

As you know, the Motor Racing Research Center here in Watkins Glen is the archive, and we struggle to be, and strive to be, the international archive for the history of motor sports. Not just in Watkins Glen, but from all over the country, and indeed all over the world. So we’re going to be talking about TransAm, and now I’d like to introduce another very special person to the International Motor Racing Research Center.

Judy Stropas. Judy for many years was the timer scorer for the Butmore Racing, also for the AMC Javelin Team and the Penske Racing Trans Am. She also was the public relations manager for Chevrolet. And it is my pleasure now to introduce and turn this microphone over to Judy.[00:02:00]

Judy Stropus: panel. We have certainly people from the past and present who will, uh, help decipher all the secrets and all the maneuverings that went on back in the day and probably still go on. So now I’d like to introduce our panel. And because, as I said, we cover the gamut of several years. All 50 years, pretty much.

Although the last few, I don’t think we have anybody representing the last few years. So I’d like to introduce Chuck Cantrell. Chuck is a graduate of General Motors Institute in 1956 and he raced in SCCA in the 50s and joined GM Styling as a GM tech center as an engineer in 1960. He continued to be an avid SCCA racer.

I’m sure you’ll all correct me if there’s anything wrong with the title. Winning several divisional titles in F& B production and joined Ford Special Vehicles as a Shelby American liaison for a Mustang program. [00:03:00] Also working on the GT350 and 500 programs, spending three years in Trans Am racing with children.

Followed a 68 race season, he joined Penske Racing as race shop general manager in 2009. for the road racing teams through 73, which of course included a team’s Trans Am wins in 68, 69 in Camaros, and 71 through Javelins. Lee Dykstra. Lee also attended The General Motors Institute and work for Cadillac. He joined Car Craft as a race engineer from 1968 to 70, working on the Ford GT and the Trans Am program, where he was responsible for the handling package for the Ford ESV safety car.

He was also responsible for the design and development of the 1968 to 70 Trans Am Mustang. which won the championship in 70. Since that time, he started Econ Engineering, designing the Insta Title winning Chevy 77, designing 19 complete race cars for a number of series, as president of the Special Chassis, and director of technology for Champ Car World Series.

He was race [00:04:00] engineer for many years after that, for a number of open wheel series. John Woody Woodard. Woody worked for Penske Racing for more than 30 years, beginning in 69. In the first eight years, he was a full time race mechanic. In particular, he was the chief mechanic on Markdown. He was 1969 Trans Am Championship winning Camaro and the 1970 Javelin.

He was also chief mechanic on Penske Racing’s Sunoco Ferrari 512, below the Q192, the owner of Porsche 91710. Porsche 917 30 and worked on the NASCAR team fielding the AMC Matador and Mercury Montego. Who remembers those days? Um, continued to work for Penske Racing, another business that was a weekend warrior, through 89 on the IndyCar team.

He retired from Penske Corp in 1999. Don Copps. Don was Penske Racing’s first and only engineer from 1969 76. He started his career as an engineer in Chevrolet’s R& D department. 1964, he graduated from what he said was Kettering University, but that was [00:05:00] originally the General Motors Institute in 1962 and worked for Chevrolet on the Chaparral Project 66 to 68 before being assigned to Penske Racing to project in 69.

He left GM at the end of 69 to work Penske Raisings, TransAm Javelin program through 76. He was involved in all Penske Raisings project.

He also ended up doing business with Penske and ventured into the Detroit diesel business in 76. He retired in 2001 and now spends his free time driving the PCA events in the Northeast including Hawkins Lane. Tommy Kendall. Tommy began his career in S& GT driving a GT Mazda RX 7 and winning the 86 and 87 championships.

Later he won three other titles in the same car, which he still owns. Is that correct?

Tommy Kendall: Other people won three titles. Oh, okay.

Judy Stropus: I can fix this with that. He dominated the SECA Trans Am Series in the 90s, scoring four championships, racing a Chevy Beretta and a [00:06:00] Ford Mustang to those titles. In 97 in a Mustang, he won every single race on the schedule except for the last two, and then represented the series for six IROC seasons.

He’s competed in NASCAR, in the Bathurst In 1991, you might remember, he suffered serious leg injuries along his way when a mechanical failure caused his intrepid GTP Chevy to leave the track and crash head on into a car wall. NASCAR driver J. D. McDuffie had been killed in the same turn a month later.

Both crashes led to the addition of the chicane on the back stretch. He called it a crossroads in his career. He did, however, return racing in 92, and later competed in the Dodge Viper in the fail and escape. Now he has a broadcasting career. Hosting shows on Speed TV in the past and now Fox Sports Club.

Butch finished second in the 2002 Trans Am Series and ended up as the Rookie of the Year. And it was his only season driving in the Trans Am Series, racing Corvette [00:07:00] for Tomboy. His career includes racing for the Bentley factory team at Le Mans, the Cadillac team at Le Mans, and Panos He earned victories in the 2010 12 hours of Stephen Long Beach and a podium finish at Laguna Seca, competing in all four races that year.

He’s driven in the ALMS series for a number of teams, and he’s competed in NASCAR races, racing three times at Wadley’s Ladder with a best finish of 12. 95. And of course, he’s the son of popular, and son, and Trans Am driver, Bob Leitzinger. So, I’d like to start with the elder statesman of the, uh, series and of the panel.

And that would be Chuck Cantwell. So, Chuck, you were originally in the series in 1966

Chuck Cantwell: when it started. In 1966, in 1965, the SEC decided to have a series called Trans Hand. And, uh, Shelby involved one of us. We had a meeting with George Murrow and Louis Bensford and myself. And I was assigned the task of We’re doing the homologation papers for the cars for the [00:08:00] Trans Am N66.

We haven’t built a car, I mean, yet, so the car was sort of designed within the homologation papers. We had to run around and take pictures, accumulate dimensions, and get part numbers for all the options we wanted to put on the car. And that was sent to Ford, and all they had to do was paste up a, a main wheel on the side of a picture of a regular Ford sedan, because we didn’t have any pictures like that at the time.

After the first of the year, Shelby gave me a budget of 5, 000 to build a car. And, uh, that included going to the dealer and buying a car. So, we did that. We built a car and then tested it, uh, uh, several times. And then we ordered 10 more cars initially. And then I, all together we built 25 Trans Am cars for customers.

We had, uh, homologated Group 1 and Group 2 cars. The Group 2 would be on the Trans Am car. Group 1 was sort of a Modified Mustang. That was a rally car. We built four of ’em to begin [00:09:00] with and they went to Europe and and Australia. So we built the cars and the, the series was run First Race was at Sebring.

AJ Foyt ran in that race, ran a mustang of some kind, not one of ours. ’cause most of the drivers at the beginning were independent drivers that built their own cars. And we sold a Mustang, we sold the parts, but they ran. Or the first race was one like Jo and. In an alpha, I believe, when the Mustang was second in that race.

Or, Tulius was second in that part. And then the series went on from there. It ran only seven races in 1966. At the end of the sixth race, uh, Mustang and Chrysler were pretty close in points. Ford asked us to run a Mustang in the. Sixth race at Riverside. We had a car that I just tested and had been finished up and was ready for sale.

Hadn’t been bought yet, so we took that car and cleaned it up. Took it out to the track with two crew guys and ran the race and won the race. It wasn’t an [00:10:00] easy, particularly, it was sort of a wire to wire win almost. At the beginning, the car wouldn’t start until the Le Mans started, so he didn’t get off until the middle of the field.

And halfway through the race, he managed to, Titus, Terry Titus was driving, he managed to knock the car out. The oil filter loose and came in in a big cloud of smoke in the pits and they changed the oil filter and threw in four course of oil and hooked. That was enough, and then he went out and won the race.

So that won the championship for Ford and sort of set us up on the line to get a Ford sponsored team for the six to seven six.

Judy Stropus: I would then jump over to Lee Ra who got involved in, well, we skipped 1967. I may be the only one who was in the 1967 series on, or you were in the Trans Act.

John ‘Woody’ Woodard: I witnessed it.

Judy Stropus: I know you were, but besides you.

No, I know, but I mean, other than you. When I was with the Baltimore Cougar team, and that was an interesting, uh, I was introduced to the Cougar [00:11:00] team in Marlboro, I can’t even say Marlboro, Maryland, for a five hour race, and, uh, I got hired by them, and they paid me 25, but they, after that, it was We did a great job in my opinion, and it was hard for the rest of the season.

So let’s go to Lee Dykstra, who was very important with the Ford effort and Car Craft at the time. So how did Car Craft get involved in TransAm?

Lee Dykstra: So Car Craft got involved because Brad Fernandes, who was a Ford liaison for the Ford Motor Team, had a hold of me because we were doing the Ford long distance cars and essentially a racing engineering job for Ford, and asked about The rear suspension on the Mustang, well it had long upper link in the thing, which wasn’t compatible with the leaf spring geometry.

So we told him, this is what you have to do to it. And he must have been impressed or something like that. Because the next year, then essentially we got a couple of cars from Shelby, 67 cars. And we built the [00:12:00] 68 cars which you may have seen over at the museum. That was one of the cars that we built. So, just prior to the 24 hour of Daytona, we built the two cars, and the two cars were run by Titus and Buckner and Horst Quek and Alan Mocker.

We came in that race fourth overall in the thing, second car with Quek and Wilken Tower in the thing, so it was a DNF. Jerry’s car ran the whole thing and, uh, I can remember coming to pit stops and we put so much oil in this car that we needed one of the fuel rigs to feed the oil to. They would open the door and wipe the floor because there was so much oil in the cockpit that his foot was slipping off the pedals, so we had slipping clutch, slipping brakes, and slipping From then on, it was sort of I don’t know, it was a good thing that we did that first race because we got our spears up a little bit.

But from then on we got totally beat the whole time because we had [00:13:00] an engine that might have been down on power but was unreliable. And then we also were all homologated because the Penske cars had spoilers on the front and rear and we had nothing. So we spent the whole season, uh, eating whatever curl or whatever you want to call it.

And, you know, vowed to continue on and do this. So, we won, I think, four races and three races in 1968. And all of them were sort of by accident because we won, uh, Daytona, which is why the Penske car went out. At Sebring, we lost. We won again with, uh, Jerry, actually here at Flint. And we won at Horse Quek at Riverside.

And that was about the extent of it. I’ve got some stuff a little later with social pictures of us testing at Riverside, trying to get proper engines. So we had a Gurney Westlake in the car. We had Shelby guys, uh, John Donne, built proper, uh, teleport. We tested that. That was good. And then we had spoilers and all that sort of thing that we tested at Riverside.[00:14:00]

And came back strong in 69 with a proper race car.

Judy Stropus: Alright, so Don Cox as a GM engineer, as a Chevrolet engineer. At the time, while Ford was openly in racing, Chevrolet was still very much everything out the back door in those days, which made it very, really very exciting. So tell us about your role in that.

Don Cox: This is where it gets really exciting. Um, Lee and I went to college together. Lee and I built three race cars together after we got out of college. One of those cars was in the Mossport Grand Prix with people like Pedro Rodriguez, Jim Hall, John Surtees, Jothar Motsenbacher, all these kinds of people. And our car qualified 7th.

That’s why the Ford guy, Roy Lund, came over and offered all three of us a job on the spot. Lee and I went over to talk to him the next week. Lee ended up taking the job. I stayed with Chevrolet because I was working [00:15:00] on the Chaparral stuff and I was perfectly happy there. So, in June of 68, I ran into Lee on a ferry boat going across to Wisconsin or someplace in Michigan.

Lee was telling me how he was working on the Ford project and they were homologating all of this stuff. And they were going to beat the guy that was beating them so bad in 68. And I’m yawning and thinking, well that’s fun, that’s nice, because I’m working on all this other stuff. The chaparral and wings and all that stuff, so I was happy.

Well, as luck would have it, in March of 69, I get assigned to the Penske project. And I wake up in the morning and I think, oh my god, I’m going to be involved with the Trans Am cars. These are the same cars that Lee has been working on all of 1968 to go and beat Penske in 1969. And when we got to the first race, those cars were so fast, they beat us four out of the first five races, and the lap times weren’t even close.[00:16:00]

So, here’s two guys, went to school together, were in business together, that are exact opposites on the two teams. I’m representing Chevrolet, and Lee is representing Ford. That is my initiation into Trans Am Racing.

Judy Stropus: But my question was, about the backdoor, the Chevrolet backdoor during those early years of racing.

Well,

Don Cox: early years of Trans Am racing, I wasn’t involved in that. Penske was being helped, as a lot of other people, anybody who wanted to be helped, by the Product and Performance Group, with Vince Figgins and all these people. And it wasn’t until March of 69 that John DeLorean became head of Chevrolet.

Roger Pinsky and John DeLorean were big buddies. And Pinsky insisted on getting help from the R& D group as opposed to getting help from the product performance group. And so that’s how I got involved. At the end of [00:17:00] 69, Pinsky went to American Motors and hired me away from Chevrolet. But in 67 and 68, he got technical assistance from Chevrolet, but to my knowledge, never got a penny of actual money.

And when American Motors came along in 69 and offered Roger, I think in the order of a million dollars to run Javelins, that’s when Roger switched from Chevy to American Motors.

Judy Stropus: Jumping back to Lee, because you wanted to talk about how the three amigos, I should say hombres, You, Chuck, and Don got together, so you’re going to get some slides you want to show.

Lee Dykstra: One of the things that Don talked about was us building the car, so I’ve got some photographs just to show you the car, how it sort of evolved. I tried to do some pictures that sort of tied in some of the panels here. This is a car that we built in my garage in [00:18:00] Ferndale. So essentially that’s a brick aluminum powered C modified.

It had a space frame, it had a weight of about 1, 300 pounds. Don did the engine transmission and rear tempest transaxle. The guy driving is Bob Stout, who is another engineer who is in our same class. So he did all the fabrication and welding and that sort of thing. The body came from a place in Minnesota that built, this is sort of, looks like a birdcage Maserati.

This particular car learned me a lot of lessons because every time it went off the road, some suspension bent or something like that. We had a swing axle in the back with a totally decoupled, but it wasn’t. It gave me a damping involved. Don ended up crashing this car and totally knocked it out.

Don Cox: Which is the best thing that could have ever happened to me.

Lee Dykstra: It, uh, crashed at Waterford Hills because there was a car with a carburetor on it. And it kept cutting out in the dirt. [00:19:00] And we wouldn’t modify the body to put the proper carburetor on it. So it cut out in the dirt. Unfortunately, it ended up toting the car because of that. The second car I had, Don and I went to Ford to Jack Passmore and got a Ford engine.

And the Cadillac guys were so mad that I had a Ford engine in one of these cars, that they offered to build me a proper Cadillac racing engine. With hydraulic lifters and 300 horsepower and four barrel carburetor. So we built the car with a, um, Cadillac engine. This is still a front engine car. This is the one that raced at Mossport, where we ended up qualifying in seventh.

The thing, obviously, looks very nice because of no mold for the body. So it never looked much better than that. But it was pretty fast and the driver was Glenn Lyle. Some of you might know him that ran Ford Performance. Quite a few years. That’s how, essentially, I got into Trans Am, because I got the [00:20:00] job at Carcorac because of this car.

Judy Stropus: We’ll come back to these slides. But I do want to get to Woody, John Woodard, and his early years with Penske Racing. How did you end up getting that job?

John ‘Woody’ Woodard: In the mid 60s, uh, I was working in Annapolis, Maryland as a mechanic at a sports car shop right in downtown Annapolis. And Marlboro Raceway was less than 20 miles away.

And I went to a couple races and got interested and got my SECA license. Invested in a Lotus Super 7, and did a bunch of racing at Marlboro, up and down the east. And in 1967, I happened to attend the Marlboro, I thought it was a 6 hour race, but it could have been a 5 or a 3 or whatever. But I’m walking around the infield, the first day of practice, and this beautiful blue Chevrolet Slantback truck rolls in, with an absolutely gorgeous 67 Camaro Trans Am car on the back.

Candidates climb out, and they’re all dressed neatly in, uh, like uniforms, and [00:21:00] Mark Donohue gets out of a car, and he’s, uh, Mr. Nice, and, uh, it was just a first class operation. Gets in the car, he qualified on the pole, they started the race, and in spite of Judy’s excellent timekeeping with the footboard team, Mark Donohue left the entire field two times.

Early the next year, I went on up to work for George Alderman in Wilmington, Delaware. Figured out pretty quickly I couldn’t continue racing on a mechanic’s salary, so I sold the Lotus Supra 7. And I’m fixing rovers and stuff like that for George Alderman. And late in 68, I said, you know, I really like motor racing.

I was a pretty decent mechanic. I liked the competition. And I remembered the Penske team that I had seen at Marlboro. Newtown Square was less than an hour away. I get up one Saturday morning. It’s the Saturday before New Year’s. Bring in the New Year of 69. And I go on up the road looking for Newtown Square.

And I’m halfway there and I’m saying to myself What the hell am I doing? It’s the Saturday before [00:22:00] New Year’s. There’s not going to be anybody at Penske Racing. I drive into Newtown Square. Find a gas station. Ask them where Penske Racing is. He gives me instructions. I go down there, I find the place, the gate’s unlocked.

There are two cars in the parking lot. I drive up, park, knock on the door, and Martin Onahue opens the door. Invites me in. Introduces me to Roger Pinsky. I introduce myself, and I said, you know, I’m a mechanic. I work for George Alderman, who Martin knew quite well. And, uh, I’d like to work for you. I spent two hours, they walked me around the shop, uh, asking me a lot of questions, what I’ve worked on, you know, could I overhaul that Muncie transmission, et cetera, et cetera.

Two weeks later, Mark called me and said, I want you to start Monday. And that’s how I got my job with Penske Racing. My first job was the Bucknum, there were two 69 Trans Am chassis that were there. Both had come from the dipper, and, which is a different story. Um, one car had had the roll cage installed.

The chassis had been [00:23:00] painted, but there wasn’t a single bolt or rivet attached to it. And, uh, Mark was off to a test at GM, and then they were going to the 24 hour at, at Daytona. And he said, hey, there’s a shelf of parts for this car. Put together whatever you can. And when they came back after Daytona, the car was complete and ready for an engine.

I wound up building both. That first car was the Buckham car, the nine car. And then, uh, I built Mark’s car. I’ve been hired as, uh, Buckner’s Chief Mechanic. Mark’s Chief Mechanic was Leroy Gein. And the first race was at Michigan, which was quite a race. Judy remembers that one. Mark and Roger and Leroy had a bit of a falling out at the end of the race, and they fired Leroy Gein.

And I became, overnight, Mark Iley’s crew chief. That’s how I got my start.

Judy Stropus: Chuck, talk about your time at Penske Racing, and why you moved over from

Chuck Cantwell: Shelby to Penske. Well, I worked for [00:24:00] Shelby, started with the GP 350 program, and went to the Trans Am, three years of Trans Am racing. In 67 we won the championship, in 68 we were the lead.

We had cars that weren’t very reliable, and it was really a rather hectic season, even though we did manage to win three races. Mark won all the rest of them in 68. At the end of that year, I was wondering what I should do, and I knew that Shelby had one more year left in his contract. Since all the big international racing with the GT40s and stuff were done, I had time for him.

I knew he wasn’t too interested. He didn’t show a lot of interest in what was going on. He came to the Trans Am races, but he, he went home. This car out here was one horse quick to win the race at Riverside, and Shelby went home before the race was halfway over. So I, I thought, well if this wasn’t going to be there in a year, there probably wouldn’t be any job because Shelby Racing would all shut down.

So Roger had contacted me after the season was over, and asked [00:25:00] if I wanted to go to work there. And I agreed to do that. So I went to his house and interviewed, talked to him a while. Went to the race shop and looked around and so forth. Pretty easy decision to make, going with a top class team that had a future to it, rather than one that had, uh, its future was pretty much gone.

So I went to work for them and was very happy to do so.

Judy Stropus: So we’re going to jump a few dozen years, maybe not quite that many, to, uh, the later era, and we’ll start with Butch, his one year in Trans Am. But your history goes back to being with your dad, Bob, in Trans Am. What did you think about the series at the time as a young person?

Butch Leitzinger: Oh yeah, I grew up, you know, a racist family, so It’s not like today with racing, where you have so many different avenues, you can become, I mean, if you’re a NASCAR fan, there’s only NASCAR truck fans. Back then, if it was racing, you were a fan. Because there was so little to get, you know, you grabbed onto any bit of racing.

Of course, [00:26:00] you know, look at AutoWeek and Competition News, you would latch onto any information you had. So, I followed Trans Am all through the years. My dad raced in Trans Am in 81. He had raced in SCCA Nationals up in Zoban. You know, the family team had a, uh, 280ZX Datsun that he raced. And it wasn’t a terribly competitive car.

It was a normally aspirated 3 liter engine up against a lot of pretty heavy equipment. Tom Gloy, that year, came out with, like, Ford’s return to racing with the Mustang. Bob Solis had the Jaguar. Effie Weiss had a Corvette that was very fast. So, for my dad’s car, it didn’t do terribly well. Like, if this was at Lime Rock or at Sears Point where the handling was premier, he would do well.

Kind of the ending of his Trans Am career was, at the end of that year, the rule book came out. And in spite of having a pretty lackluster year, the rules were basically the same for all the cars at the end of the year. But it said, specific exception, Datsun 280ZX, normally aspirated, 200 pound weight gain.

And there [00:27:00] was one 280ZX normally aspirated in the country. So my dad called the competition director at the time and said, you know, I read the rule book here. I said, oh, okay. Did you see what it said? Well, we have said this. My dad said, no, no, no. That says Bob Inger. We don’t want your ass in TransAm, . And uh, they said, oh, oh, well, sorry to hear that.

So, yeah, that was kind of his departure from TransAm when, when I did Trans Am in 2002, when, when I told him that I was going to be doing it. You know, he kind of rolled his eyes like, oh no. I don’t know if you know what you’re getting into. But yeah, we’ll get to that later.

Judy Stropus: I was going to say, what did you get into?

We’ll go to Tommy Tenzel, the giant killer of the later, in the 90s and so. When you came in, clearly, the series had a tremendous history already. When you came in, did you even consider that history? Because you are a bit of a historian, in my opinion. When you started to race and you were in a Ford and competing against General Edmonds.

You were also in a [00:28:00] Chevrolet in the Beretta, competing against Ford. Run the gamut.

Tommy Kendall: Following up, a little bit of what Butch said, tell people today, to try to remember what it was like, there was no internet, there was three television channels, and there was a handful of magazines that came out once a month.

And so, if you didn’t know someone that did something, you could live your whole childhood and never know it existed. And so all of a sudden I got exposed to racing, it’s like my head exploded, and I subscribed to On Track magazine. So from about 81 on, I know everything that happened, because I used to read that cover to cover.

Before that, it took me a while, until I got more heavily involved to appreciate some of the stuff that went before that. Ironically, one of the first books I read was Paul Van Valkenburgh’s book, The Unfair Advantage. And I read that long before I ever drove even a go kart. The way things work out, and I was hell bent to get into open wheel cars, I wanted to go IndyCar racing, and budgets and heights inspired a little bit against that.

I ended up spending my whole life in sports cars, and I, you know, couldn’t have worked out better. All those years later, [00:29:00] to go up against some of those records that were set by some of these guys here, uh, it’s funny how that all works out. When you’re young, you don’t have a full appreciation for history, but I had an appreciation for what was happening right then.

So I started following Trans Am in 81. Finally got to driving in 85, 86. I did my first Trans Am race. There was a picture and it was focused on Pruitt on the victory stand. I was in a mobile one suit to the right. That was my very first Trans Am race. I was racing GTU and my dad bought that old Gloy Capri that had won the championship in 84.

And he said, do you want to run this at Long Beach? And I said, yeah. So we didn’t know anything about Trans Am cars. So yeah, I did all the legwork. I could, I tracked down Dave King who had been at Roush. I talked to Willie T, got as much information as I could. We showed up with our little ragtag team at Long Beach, qualified third and finished second behind Pruitt in the AmeriCorps.

The water main broke and flooded the garage. And everybody except Pruitt crashed in the water. I ended up backing out, lost the front end. Finished [00:30:00] a lap behind Pruitt, but finished in second. So, that’s a story that not a lot of people know. A lot of that focus is on the later years. But, you know, I was fortunate that late 60s, early 70s were the real glory years of Trans Am.

But in hindsight, I was honored to kind of be part of the second golden era in the 90s. As my Twitter profile said, I was big in the 90s. And, uh, so, you know, I was just, it’s funny how fate works out. Couldn’t be more, more minor. The cars are just kind of the perfect. Each step along the way, they were really ripe for that era.

They were quite a bit different through the years, but they were appropriate for what got people excited. And that includes today, one of the things I say. Very few series now have as much power as they used to. Everybody talks about the glory days of K& M, big horsepower. The glory days of MCGTP, big horsepower.

The only series running today, where the most powerful cars ever are running today, are Trans Am. Those cars are, like, almost 900 horsepower now, 800 and some horsepower. And Sprint Cup, they’re about 900 horsepower as well. Everything else is less than their [00:31:00] glory days. And I’m, you know, it’s a little newsflash to some of the people running these series.

If you want to get people excited, people like the big power, so.

Judy Stropus: Well, tell me about the Heredity. I mean, that is like an almost forgotten. It was hard to find anything on Google, and yet I was there. I was part of the Beretta team. Talk about that adventure with Chevrolet.

Tommy Kendall: I was really indebted, really, to Herb Fischel.

He kind of cherry picked me after I won those two GTU championships in the RX 7. I was going to school at UCLA, and he had this idea that race car drivers were going to become more You know, it’s going to be more about marketing and they need to be a little bit articulate and so forth. And so, he called me out of the blue and wanted to talk to me about a new program at Chevy.

And this was, they were more involved in the racing, but it wasn’t really totally above board. We’re proud that we’re in racing. So things were changing. In 88 they had a production car called the Beretta GTU. And they had a corresponding race program. And so I did that. We won the championship the first year in the Beretta.[00:32:00]

It was supposed to be two years. They said, well let’s switch it over to Trans Am. So that’s how the Beretta went into Trans Am. The team was run by Cars and Concepts out of Brighton, Michigan. And the person who designed that car was a guy named Trent Jarman. Lovely guy. But he was Employed at Cars and Concepts as an engineer designer.

They made sunroofs and convertible tops for automakers. And he designed this car. It was not so hot as you would maybe expect. And so we were throwing huge money at this and didn’t get any results. It’s been a second in the championship just by hanging around. Dorsey, you know, the rest of the guys pretty much comprehensively destroyed us.

Chevrolet hired Doug Fehan, who’s still involved in the Corvette program. to kind of assess the program and give his recommendations. And he came in with his whole list of stuff, which included firing both drivers. And so, fortunately, Herb went to bat for me and he says, We’ll fire one of them, but we want, you know, we’re sticking with Kendall.

And so, Bob Riley [00:33:00] designed that. 90 Beretta, which I look back on it, then I convince myself it looks like a Beretta. It’s one of the wilder looking pieces ever and Judy was a part of that program and we kicked off in fine style. We didn’t win a race until Cleveland. But they were adding weight to us even before we won, but won six races that year, and won the championship away from Roush, and uh, Chris Nifle was my teammate, we were the twin towers of Trans Am.

Really a cool program, and that GTU stuff, even though I won the three championships, Trans Am was finally getting into the big leagues. And you were running in front of big crowds, you were in the sport race for IndyCar Weekends on Saturday, it was really great. Trans Am on Saturday. At the Glen we ran with Winston Cup.

One story about that race, which sticks in my car, one of the races that NYFA won. They were adding weight to us, and so we were kind of starting to manage how quick we were showing in practice. And so, it was really getting bad, they’d added weight a couple times. And they said, listen, we’re really racing Dorsey.

We’re not racing the Dodgers, we’re not racing anyone else, we’re racing Dorsey. So, we’re going to key off of him. [00:34:00] We don’t want you qualifying up front. We need to be near the front. And so, I think I qualified fifth, which was my worst qualifying all year. And so, before the race Thien says, you know, just kind of watch him.

I don’t want you leading. If someone else is leading, let him go. Keep your eye on Dorsey, look up on him. And so I’m running around, like, fifth place, whatever, and Knifel is going to front. And he’s all over the leader. And then I’m like, technically he’s not leading, but it’s obvious he could be. It wasn’t a very good show, I didn’t think.

So all of a sudden, I think Dorsey dropped out, or maybe it was the IS car. All of a sudden I see on the radio, I said, what’s, what’s the deal? I said, deal’s off. Go for it. And I’m like, fifth and knife bullets way out in front. Knife and ham were really, really close for a lot of years. So there was a little interesting team dynamic going on.

So I got on my horse and I started reeling in knife. I caught him on the last lap. I got up next to him on the back straightaway and he ran me into the grass. And we were about to almost wreck him. And I was [00:35:00] hot. And so we were on the short course coming back. And I got partway alongside him coming into the final corner with a checker.

And I felt like I had, I was far enough alongside that if we hit it was going to be at least shared responsibility. But something told me that that argument wasn’t probably going to hold a lot of line. And so I got out of it. He chopped across. He won the race. And I felt like I’d been kind of hosed. And I was As racers, you’re totally Everything is egocentric.

It doesn’t matter. Team goals, all you’re thinking about is how to fetch you. So When Eiffel won, that was his first one of the year. I’d won, I think, four or five at that point. But, that was Little Trans Am related trivia inside the story. And then one of his friends is an artist and did a picture of that.

And he wanted me to sign, I sign, I

Judy Stropus: sign. Over the years there’s obviously been conflicts between the sanctioning group and the race teams and the manufacturers. So I know there are stories. Now I don’t know if Woody’s story about oil pan [00:36:00] testing in Elkhart Lake has any connection to SCCA’s rules. But I know you have a story.

John ‘Woody’ Woodard: I do have a story. Before I do that, I want to clear one thing up. In deference to my counterparts around me. I never attended nor graduated from General Motors this year.

When Roger signed the deal with American Motors to take on the Javelin project, it was a big project because there wasn’t much to start with. The Kaplan, uh, prior team was really, all they left was a house of junk in Southern California and we really had to start from scratch. There was an engine program in place from 67, Where, uh, Treco had built the AMC motors, and they were pretty successful at it, they had good power.

In 1969 and 70, we’re not allowed to dry sump. The rules were, stock oil pump, and basically a stock oil pan, although they didn’t bother you too much on the oil pan. We used the stock oil pump, and we took our best shot at the oil pan. And we learned [00:37:00] that in racing or testing, if there were some long corners, you know, the carousel, the down part way, or the like.

We were losing engine bearings. We were losing the oil pressure. It cost us a number of races early in the 1970’s season. And Mark decided that we needed to fix it, do something. You couldn’t remove the oil pan and the javelin without pulling the engine. And he had me take one of the two race cars and cut the center section out of the front crossmember and put flanges on it so I could bolt the crossmember in and out.

And he got five different aftermarket Southern California hot rod types to build five different configurations of oil pans. One of them was actually a big circle that had the oil pump feed came out of the center, and it was in a bearing that had this big thing swinging around no matter what direction it went.

Anyway, that one didn’t work.

Judy Stropus: But we

John ‘Woody’ Woodard: went to Elkhart Lake. For three days of testing, and [00:38:00] we tested oil pans, and back then, we didn’t have recorders. And Mark says, you know, I can’t drive the car and watch the oil pressure gauge. Unless I can, but then I can’t go as fast. As I need to go to see if we can destroy the engine.

So he says, you’re going to have to ride in the back. So I would change you, I would change you off him. And then I’d climb in the roll cage and there was no seat back there and there was no seat belt. I would kind of look like a monkey with a roll cage looking right over his shoulder. And he would go out and do laps through that carousel, I mean, just absolutely as fast as he was qualifying.

And I’d watch the oil pressure change. And I’d, up, down. I think we tried four different oil pans and we finally came up with one that would lift through the carousel. And we went home, and I don’t believe we ever failed another engine, but I was black and blue for a month.

Tommy Kendall: Now, every team has one or two or three dads, dad [00:39:00] acquisition geeks.

That was a dad acquisition stud. Want to add something?

Judy Stropus: I

Don Cox: did a similar thing. Mark, we were trying to, uh, learn something about pressures and air flow and on the car, so we were at, I think it was Donnybrook, and I didn’t really know about this before, but apparently it was something that Donny played on everybody. But, uh, I was ended up strapped into the back of a Camaro, using the same straps that you would tie the car down with in the trailer.

And, uh, trying to read these manometers as he was out driving, and it became kind of clear early on It wasn’t working so well, so. The plan was that we would go out and try to run a constant speed down the straightaway. You know, so many RPM, constant speed for the length of the straightaway. And then we’d go in and make changes, [00:40:00] and then go back out and run the same constant speed.

And try to see if we got any difference in these water manometers. This is the crudest thing you could ever imagine. But Donahue grew impatient with the whole process, so he finally, he just started driving really fast. I’m back there, scared half to death. And I looked up one time, and we’re going down the straightaway.

And we’re not going the standard, you know, 100 miles an hour. We should, he’s just flat out. And I’m seeing RPMs of 7, 7, 500. I look at the turn coming up, and I look over at his helmet, and I look at the turn coming up. And he’s not moving, and I’m convinced that he’s dead.

And all at once, he, you know, the car, he jumps on the brakes, the car slows down. To this day, I have, I wake up in the middle of the night. I have

Judy Stropus: a story similar. During the Trans Am series with the Camaro. Winning at Riverside, when Mark won at [00:41:00] Riverside, I think that claims the championship. It would be the only time that I said that I would ever ride in the passenger seat with the flag.

And so they put me in there, pictures of me being pushed in and dragged out, because as soon as Mark saw it was me in the passenger seat, and I was given the flag to hold, I held on to that flag. So hard, and he drove a regular, normal Trans Am racing lap, with me in the passenger seat, without a seatbelt.

And when we got back, the flag was in tatters. It was totally destroyed, but I held on to it until the bitter end. But that was Mark, he was a practicer for sure.

Lee Dykstra: Oh, I think that’s a driver thing too, because I rode around in the car, sliding on my haunches in the front seat. with George Fulmer going around mid Ohio, and we were third on the grid at the time with me in it.

I’m trying to engage. But along Woody’s stories, we [00:42:00] have some good oil pan stories too, because essentially the Ford engine sits in front of the crossmember, and the oil pan section is in front of the engine, so essentially whenever you accelerate, all the oil goes to the back, and you lose oil pressure.

So, Ford had this miraculous electronic sensor so they could tell when it was bad and this sort of thing, and they said, you gotta do something with the oil pan. It’d become a competition between Car Craft and Ford Engine and Foundry because both of us were trying to do a proper oil pan for the thing.

We at Car Craft, we had an oil pan with a little plastic thing over the top, in the back of a station wagon. So we had different little sensors. One of the pickups, one of the things like Woody was saying as far as how to pivot, so it could pivot around. Another one we had was from a jet aircraft that sits in one of the oil tanks there and it’s like a A lead wave on the end of a flexible thing, which the Ford management called the dick pickup.[00:43:00]

And we, you know, got dizzy riding in the station wagon, watching the oil move around and that sort of thing. So the final solution was, the guy that was my design guy, came up with a double oil pump, driven by the same shaft, and then we had a pickup in the back of the thing, plus various windows and that sort of thing.

Essentially part of the oil pan picked up in the back and dumped in the front, and then the proper oil pan pump could pick it up. Well, Ford E& F at the same time designed this cast aluminum pan, and it was near Christmas, and one of the Ford guys came in and he was on crutches. And Fran Amanda said to him, What happened, you dropped your oil can on your foot?

And so, And that oil pan never saw the light of day because it was about 60 pounds or something like that.

John ‘Woody’ Woodard: I want to stage a revolt against the 1970 Trans [00:44:00] Am. Because you had a cheating roll call. You were only allowed one.

Judy Stropus: Speaking of cheating. Yeah. And the roll calls and the rolls and the calls. All of you.

I think all of you were. I know the early ones were. I can’t speak for the late ones. But that was one of Roger’s great calls. to read the loopholes and work them to the team’s benefit. So I know all of you have something to do with that. So what about acid dipping and all of those things?

Lee Dykstra: We were at the L.

A. airport, and there was some chassis sitting there that were going to be shipped back to the Midwest. And so they were acid dipped and they were Camaros. And we wrote on the thing, This chassis is not legal for trans animals. Laughter

John ‘Woody’ Woodard: I have a funny dipping story. It’s a funny

Judy Stropus: dipping story.

John ‘Woody’ Woodard: I [00:45:00] believe everybody dipped their cars back then.

Osi’s cars were dipped and I know Chuck’s cars were dipped.

Chuck Cantwell: right? Not uh, well No. Okay,

Judy Stropus: so this

John ‘Woody’ Woodard: expires My story. We did acid dip the 69 Camaros and right when we finished painting them and we never noticed, the roofs were, didn’t look quite right we had no time to replace the roofs So Mark went down the street and got one of these Landau roof guys to come in the shop and they put rubber roofs on both cars.

And we went off in the races with a Landau roof on the two Camaros. And the Ford guys didn’t like it. And they’re complaining to John Tomanas, the head of technical inspection, just the greatest guy. And he’d come over and ask me, you know, Woody, off the side, you know, what’s, what’s with the rubber roof? It just, it just, it makes it look good, you know.

Roger. So we get to about the 4th or 5th [00:46:00] race, and Kurt beat the bet. And Ford was really putting a lot of pressure on the FCCA. And Tenus comes over to me again, it’s going off to the side, Woody, you gotta tell me what’s going on with the rubber roof. And I said, John, I can’t believe you ever figured it out.

It’s a golf ball effect,

Judy Stropus: And he looks at

John ‘Woody’ Woodard: me and he says, what do you mean golf ball? That guy said, have you ever held a golf ball? Yeah. Doesn’t it have little dipples over it? I says, yeah. I said, John, that creates lift. And

Rick Hughey: he just

John ‘Woody’ Woodard: walked away shaking his head.

Judy Stropus: Well, I have a similar story. As a Chevrolet representative, I had a fleet of Chevrolets, usually Camaros, in New York City to get to media to write stories about.

And at the same time, Jim Hall was running the Chaparral Camaros. And they were being sort of checked by SCCA. SCCA would never go to the manufacturer to get what they think was accurate information because they didn’t trust [00:47:00] the manufacturers to give them accurate information. So, Jim Hall shows up with a head with splayed valves in it.

And they said, that can’t be stopped. So I go to a party somewhere in New York, I don’t know what the event had to do with, and John Tomatis was there, and I drive in with one of my Chevrolet cars, and it’s a Camaro, and John says, Oh, let me take a look at that car. He opens up the hood, he looks in, and he says, Oh, dang, it’s got sled belts.

He says, You were put up by a Chevrolet to bring this car to this party. I know it, I know it. And I swore that’s what they believed, but it was clearly not true. Even when I raced the Chevy Mazda, they wouldn’t believe that I was a Chevrolet representative and I gave them the stats and the technical details about the car.

They wouldn’t believe me because I represented Chevrolet in any event. So, coming back to more recent, in your one year,

Butch Leitzinger: which

Judy Stropus: you had some issues, traction control.

Butch Leitzinger: Yeah, it was a very interesting year. I drove the Tommy [00:48:00] Bahama Corvette for Tom Floyd. Two or three races I did a pretty poor job. But then we got on a roll, and we won a few races in a row.

At that time, so it was 2002, traction control was the kind of magic. If you had traction control, you would win everything. I never actually saw it, but apparently in SpeedSport News, somebody advertised, it’s like a chip, just something that you kind of like put on your MSD box, on your little, like, ignition box, and it gave you traction control.

It was supposed to be like this big, and hide it in your pocket. So everyone was convinced, if someone did well, well, they obviously had traction control. We were at Fleur O Vier, and I won. Afterwards, we pulled on the track in front of the pits, and I got out, and no one was there, which was kind of odd. And I looked over and I saw the team was kind of corralled over this area.

So I ran over to them, like to high five and stuff. They all just kind of had their hands in their pockets, and they were kind of standing there. And then an official said, Get out of here! Get back over there! This is really weird. I walked back over to the car, and then there was an ambulance parked there.

[00:49:00] And they said, Going to that ambulance. This is really weird, but the Vickery Circle is on the other end of the street, and I thought, well, maybe there’s going to be a ride down there. So I was getting in the back of this ambulance, and I closed the door behind me. These two people, doctors in the front, gave me this look, and one of them said, we’re really sorry about this, butch.

What the hell have I gotten into? And they made me do a script search. I have to say, I ought to be somewhere. I took a little bit of a shutout for the race, I have to say. You know, and they invited me, obviously. They tore the car down quite a bit. They took the MSE boxes. They’re going to send them out to testing, and then the next race was, I think, Road to America.

We got there, and they were supposed to be returning the MSD boxes. Well, well, we don’t have any yet. Bill Fingerlo was our team manager. He said, well, instead of having to buy new boxes, we have two from last year. Can we use those? And apparently, from the year before to this year, you had to use a spent MSD box.

But the year before, you were allowed to put silicone all over it to keep the bits from rattling off. But the year [00:50:00] after, you couldn’t. But, you know, they said, well, we’ve got these from last year. Can we use these instead of, you know, making us buy new ones because you didn’t get finished? So they said, okay.

So we got through that weekend, the next weekend in Denver, after the race, one of the other teams looked at our MST box and said, Hey, those aren’t the spec M MST box, the SCCA guy, the, uh, the tech guy who approved it said, oh yeah, you’re right. So, uh, and that started off this long legal thing. Tom actually hired a lawyer and spent a lot of money, basically for the rest of the year going through appeals and things.

I think what ended up happening is they. We did one of these, well, we weren’t really at fault, but we were still kind of at fault, so they gave us the win back, but they took points away or something like that. So, and really, the net effect of all of it was that Tom Gluck, I’m so fed up with everything, and he just packed it all in at the end of the year, and that was it.

But, it was a very, very interesting year. And your dad

Tommy Kendall: said [00:51:00] That’s what they did to me when they told me to. Now, I have to ask you, was Paul Genovese in the series? That’s usually where these things start.

Butch Leitzinger: Yeah, he was pretty good about kind of pointing the finger around. There’s a little bit of Richard Penny syndrome, I think.

They must be cheating, because I’m cheating and they’re beating me.

Tommy Kendall: Well, the traction control thing didn’t start in 2002. I first started getting it in 1990 with the bread. separate fifth wheel chaparral and that’s where the Chevy engineers worked out and that was their office. Everyone was convinced this was NASA control and this is where all the stuff that was being manipulated and that’s where the traction control was being beamed to space or something and so they came up with this idea that one of the, I think it was Rhode Island, right before the start of the race they were going to go over there and they put a padlock on the trailer and they said you guys can’t go in there.

And they said, okay. Then, we won. [00:52:00] The car still ran, and so forth. So that’s where the traction control started. In 97, when we were on that street, it reached a fever pitch, and the car got torn apart every single weekend. And finally, between races, on like a mid week, there was a call to shop at Roush, and they said, we want to inspect your car at the shop.

And they’re like, okay. And they’re like, when? And they’re like, right now, we’re here. And they did a sneak attack. And we’re like, knock yourselves out. You know, and so, they went, did all this stuff. And Jim Lozzi is a smart guy, but what he does is he observes something, and then he works backwards and creates this crazy I’m not sure there really was a module for sale in SpeedSport News, but when he tells the story, he’ll say, I know it, you can buy it, I’ve spoken to the guy.

Butch Leitzinger: Actually, that was one of the things that Boris told me. Because Boris said he was racing at the same time. We raced at Cleveland. In qualifying, it was my first time at Cleveland. And, unfortunately, I was reading the schedule. I went out instead of time, and my plan was to come in, bleed the tire pressures down, and go back out for a second run.

So I did it in [00:53:00] time, came into pits. Tom Gloy puts the Winternet down and says, What are you doing? It’s a ten minute session. And put the fear of God into me. And I put the thing up and I got out of the pits really quick. And I set a time and I got on Paul. But Boris told me that Paul came over to him afterwards and said, Did you see that?

They’re totally cheating. Cause he came in the pits, they just took the Winternet down, put the Winternet back up. And then he gets Paul somehow. And Boris is a good guy. Just looked at him with a dead face and said, Oh, well they’re cheating. Well,

Judy Stropus: Tommy, I do remember one point when SCCA was penalizing drivers for being too fast,

Tommy Kendall: right?

It was kind of what’s evolved. It’s out of control today. It’s what BOP is today, balance of performance. Back then, they wouldn’t do it every race, but they would kind of tell you. At one point, it was if you stick up the show and you get too big a lead, we’re going to put out the pace car and so forth. So, but that 1990 season, they added weight.

We had a split valve. [00:54:00] Fuel injected V6 Beretta, really. One thing I learned is you don’t want to be the only person running a package. Because it’s easy for them to zap you and slow you down. So that, they added weight to the point where at the end of the year, We were, with a V6, we were the exact same weight.

Chevy, we were battling for the championship. And so they ran a third Beretta with RK Smith. And they went back to a non split valve head with a carburetor. And that allowed the car to run 175 pounds lighter. That’s where I gained my appreciation for weight. And the effect on performance because, uh, RK ran the car at Mid Ohio.

We clinched the manufacturer’s title, or the driver’s title, at Mid Ohio. And then, uh, we get to Elkhart on the test day, and RK was used to, he was a formula car guy. He didn’t have a lot of experience with sedans, so he said, RK wants you to drive his car and make sure it’s, everything’s in the window and so forth.

So I got in his car and went out on a Thursday. And I went out for 3 laps and I came in and I told Dan Biggs, my crew chief, I said, I’m racing this car. He says, what do you mean? I said, I’m racing this car. This thing is so much [00:55:00] faster. It had less power, I took it, it was 175 pounds lighter. And I, I raced that car and it was one of the easier wins I ever had.

I remember going down the straightaway into turn 5 with some of the Mustangs and stuff. And I remember just looking at them, not even really paying that much attention to the brake markers. Thinking, I’m just going to wait until they brake. And when they brake, then I’ll brake. And that’s how I work my way to the front.

And so, I own that car today. And it’s how it drove off the racetrack at Safe P. I get why you want to try to equalize, but it just kind of underscores that it’s really, really hard to do any sort of equivalency formulas in racing. And I really think they need to figure out a better way than BOP to do it.

Basically, where it got to in the 90s was everybody ran a 300 inch safe carburetor. Then if you’re getting beat, you’re just getting beat. And so, it opens the can of worms where whoever’s there last threatening to withdraw gets the extra sugar. It was a nightmare. Part of the deal. It wasn’t too bad. When you’re in the middle of it, you think it’s the worst thing ever and [00:56:00] they’re allowed to get you and so forth.

So, one thing I’ve learned up here from this, Roger Penske, if you sponsored his cars, you were going to win races and you were going to lose people at the end of the year. Because it looks like he poached people and they stayed with him. for the rest of the time.

Judy Stropus: Roger was excellent at that. In fact, many of the people who were still with him or have retired recently were there early on and he snatched them from American Motors, from Sears, from Chevrolet.

He has a great kn about putting the right people together.

Tommy Kendall: Was Roger always together? There gotta be some moments where he showed up and his hair wasn’t combed. never happened. Never happened. I did a Facebook Live this morning and I looked in the mirror afterwards and my eyebrow was like all crazy. I just did a broadcast of 5,000 people so I could never drive for, that’s why I never drove for Roger.

I did see him drink a glass of wine once.

Lee Dykstra: So I was just at an event this weekend. I met someone and said, Oh, well I saw Roger [00:57:00] Penske at NASA. I was walking by and he said, Hey guy, can you give me a hand? And he was the only guy on his car. And he said, could you tape my helmet please, because I can’t see with the sun shining in the eyes.

So this guy’s shining moment was to put two strips of tape on his visor so he could see in the sun.

Judy Stropus: This might be a good time to Jump again to current season

Tommy Kendall: this year during the Petit Le Mans. A lot was made about, uh, Christina Nielsen being the first female major motorsports champion in America. And that was not true because Amy Haruma was.

All privateers now. There’s no factory involvement there, and it really takes you back to when you first got started. And those teams, it’s her dad, it’s her sister, it’s her, and I mean, the extra few bucks for an extra West Coast race, and all the things. And so, she just really kind of, the core appeal of Trans Am has always been the privateers that support.

And they’re the ones that have kept it alive, [00:58:00] because the factories come and go, and so, it’s cool to see. They’re out in the big fields, and she touched on that. That big power, those things are nasty, those, those new cars. And like every driver, your car is your favorite car. So, you know, you picture it, you always picture it.

The new season, the new paint job, what it’s gonna look like. And like Junior Johnson said, I’ve never seen an ugly car in victory lane, so. Okay.

Judy Stropus: We’ll be doing questions in a little while, Doxtra, you had some other slides you wanted to show.

Lee Dykstra: I included some of the guys on the panel there. So, let’s jump in.

Testing at Riverside, essentially with a 68 Mustang. Now this is the car that you see in the museum, or the sister to it. And we’re testing aero stuff at Riverside, as long as you can see the little bubble in the hood. So that was a Gurney Westlake engineer thing. So, trying to give the driver an idea of something, a proper motor in the thing, as opposed to the Tunnelport Ford, which had And [00:59:00] zero of about zero or 7,000.

So this is our first 69 car. coming out of the shop at Car Craft. Judy is probably familiar with it because this is the car that somehow or another the SCCA scoring missed a lap and Parnelli did an extra lap before he got to check the time. Timing and scoring stuff happened to be in Rogers plane heading out right after the race.

This is the car we built for Smokey Unik. Absolutely for a Ford Vice President type of thing. It had to be absolutely perfect, and it never ran and got cut up by torches to run on. Circle track stuff. Okay, so this is actually the first car test in the Lockheed wind tunnel in Atlanta. They didn’t have the ability to drive the car into the tunnel.

So we had to drop it from the ceiling through a hole in the tunnel. So here it is, about 60 feet in the air, [01:00:00] supported by the four cables, as we’re dropping it in for the aero test. Okay, so there’s the hole in the tunnel to drop the car through the ceiling. Here we are standing underneath it. So you can see Fran Hernandez over here, myself in the center, and Mitch Marshe, who is my design engineer.

So we’re rolling the car into place. And now they can drive the car in the tunnel and everybody and his brother is tested in the locked in tunnel. Some of this stuff you probably haven’t seen, I think this is in one of the Trans Am books or something that people have as far as some of the additions we had in the front spoiler trying to get front down force in the car.

The adjustable rear wing on the back, that’s that full cap there. So we ran through the angles as far as the rear wing is concerned. Okay, so this is a windshield wiper test. You can see the wiper’s straight up, so that’s the minimum drag position for the wiper. Now there just happens to be this funny looking thing on the roof there, which sort of looks like the rear wing that was on the back there.[01:01:00]

One of the Ford guys thought that maybe you could put downforce in the middle of the car, this way, so it was balanced. Needless to say, It didn’t quite work because the air started flowing in the wrong direction. Yeah,

Judy Stropus: yeah. Alright, And, uh, I think, Chuck, did you have something to add and some slides to show?

The

Chuck Cantwell: 66th season was the first season. That was run pretty much by independent people. But, they didn’t quite go to the first race at, uh, Sebring. There was only a set of race series. The cars had to have the completed periods, including back seats, and all of the formats, and everything on the carpet. So, they were sort of a strange thing from what people have been racing before.

And, uh, they had a single carburetor, which gave about 350 horsepower. For 67, when the teams got involved, SEC allowed larger wheels. They had to be homologated cars, but they had larger wheels and, uh, two carburetors set up. 400 horsepower. [01:02:00] That’s what we raced with. The season started for us in the Mustang.

We got our cars. They, in the year after the first of the year, had to build up two cars to get to Daytona in February, which was a pretty strict schedule. We didn’t even have time to paint the cars. We ran them there, blew a tire on the banking, and managed to save them a 160 mile an hour. Which was probably a good deal, because the only safety structure we had in those cars at that time was a roll bar.

And that wouldn’t have done much good if you went into the fence. The, the Sebring, Sebring race, they got the cars painted and Titus was on the pole. He beat the pole time from the year before by 18 seconds. And, uh, you know, Parnelli was right behind him and Thompson right behind him. So, but all the cars were much faster than, than the year before.

The next race at Green Valley, Titus rolled the car in the afternoon. Tore it up really badly and the crew worked all night on it to rebuild it. And it looked like a new car when it came back on the track. That was a real hot race. We [01:03:00] didn’t that one. And so we went through the, the season, uh, we got hired pretty badly at Briar in the rain and lost that car by the end of the year after the last race, it mixed the last race.

It started us. Not only he would run two race, won two races, Shelby and the Mustang, and won four races. And the Cougars had won four races. So the points were very close. We went. The last race at Camp Raceway, Titus had a breakfast crash, which really destroyed the car, the one day overnight fix for that car.

So, Buckman drove our other team car, of course, and Titus drove John McComb’s car, which blew up. So, during the race, anyway, Mark Bayou and the Camaro ran away with everything. So, the championship, what all happened, we got second place with a Cougar or a Mustang. It finally blew up, but before it blew up, he had showered in blood.

Gurney’s windshield with rocks, and uh, Bucknum’s car was overheating, but Bucknum was in [01:04:00] second, and Gurney was in third. Bucknum trying to keep the car from blowing up, and Gurney trying to keep the windshield from falling in on his lap. And so they ran around that way, and Bucknum ended up getting the, uh, second place, and that gave us the championship for Mustang.

With, uh, a two point edge. We, it was the best, they had twelve races that year, and then they took the best nine out of the twelve races. We had a seven point advantage on Brooks, but when they took the best nine, we were down to two point lead. So it was a really close championship. The Cougar tech inspection, at the end of a race, was they would take the car off the track and weigh the car.

Bud Morgan convinced the stewards that everybody started the race on brand new tires. He would like to start putting new tires on the car before they went away to the cars. But what they didn’t know was that the new tires that Bud put on the car were half full of water. That added a little weight. And then at one race they found no one in the passenger [01:05:00] seat with a bar of lead on it.

I

Judy Stropus: was walking with Budmore to the inspection, and he was walking with the weights all in his pockets, and they were hanging, and I said, what? Chatting with somebody who’s thrown into the helmet. And, uh, Charlie Raines walked up and said, oh, we gotta move that helmet. He moved, he picks up the helmet, and he drops it on was pretty funny,

Chuck Cantwell: yeah.

Yeah, and it’s true. They didn’t do anything about this kind of violation. You know, the competition was some And, uh, the whole racing scene was so crappy, but with the Trans Am cars, they were really a fun car to watch for spectators and for anybody who was involved with the cars. It was just the beginning of a, as you heard here, how it’s progressed up and down over the years.

It was certainly a good beginning for the Trans Am series.

Judy Stropus: Great. Thank you, gentlemen. Thank you very much. And we’ll open it up for questions. If you have a question, please raise [01:06:00] your hand if I can see you. Yes, go ahead.

Rick Hughey: Yeah, thank you, Judy. You talked about acid dipping bodies. Were there acid dipped engines, too?

No, not as far as I know. No.

John ‘Woody’ Woodard: The bodies that were acquired were trucked out I believe there was only one company that could do it, and it was in Torrance, California. The bodies that were acquired would be shipped out there. I witnessed 70 cars being dipped. And with Mark. They would only do it at night, because there was a, it looked like, it would have been a cloud of mustard gas going on, but they didn’t have time to do it.

Rick Hughey: Well, in Donahue’s book, it talks about a series of engines taken off the line at Tonawanda and Buffalo, and acid dipped, and then taken back to be put back on the line to be finished, and that they were painted pastel colors. Do you know that story?

John ‘Woody’ Woodard: I was never involved there. I don’t recall ever having We’re hearing about it, and I’ve read Mark’s book a couple of times, so we’re called reading about it.

Well,

Rick Hughey: it’s in there, and I went to [01:07:00] Tonawanda for a tour a year ago, and I talked to the history guy there, and he said, Must have happened on a weekend.

Chuck Cantwell: I think it was when he came to Chevrolet, where Mark lost track, or Chevrolet lost track of him. Yeah. So he never got the image. Yeah. Are any

CROWD: of you guys working with Historic Trans Am to ensure that the cars continue to be illegal?

John ‘Woody’ Woodard: I have been asked to look at a couple of cars to give my judgment as to whether they were our cars. And I’ve done that on a number of occasions. All of our Cabarros, two missing up until recently. The Buckman car from 69 was sold to a, uh, a Mexican businessman. And it was in a storage in a underground garage under a tall office building.

When the 1984 earthquake in Mexico City came down, and it’s, it’s down there a few [01:08:00] hundred feet still, never to be seen again. One of the six, the one missing 67 car which went to Germany was just acquired in pieces by, uh, Pat Ryan. And it is, uh, now on national, it’s after life. All the rest of them are alive and well.

I think most of them are in Southern California. I’ve seen all of them. They’re all painted Sonoca blue and not one color matches the next one.

CROWD: Laughter. Can anybody offer any credence to the story that I don’t know the race, but I think it was Donahue and Fulmer both qualified the same car for the race.

Donahue and Fulmer were never on the same team in Trans

John ‘Woody’ Woodard: Am. Donahue and

CROWD: Fisher,

Chuck Cantwell: Fisher. But Donahue qualified, I think it’s secret, both cars for, uh, Trans Am and for Fisher. And the cars were different. One of them had vents and one of them didn’t have vents. But they just changed the numbers and nobody paid attention to this.

CROWD: If you can clear up any of you on the stage, the old Hertz rent racer and light of rock gates just [01:09:00] passing away, wasn’t there a story about they took Shelby three 50 and actually raced it, sent it back to Hertz after the race, or is that a figment of my imagination?

Chuck Cantwell: Well, there there were a lot of stories about Herdz cars being raced.

We don’t think any of them are really valid, but at one race, Tom Yeager borrowed the carburetor off of John Bishop’s GT350 Hertz car that he had, and used it on his Wicks car. And I think the marker will translate on that.

CROWD: Brock could have started the story. He could have. He would.

Chuck Cantwell: He’s a strict

Judy Stropus: rider. He was a script writer, an excellent one, and of course used editorial license every time.

CROWD: When you’re talking about the acid dipping, I guess that’s to take weight off of the metal of the body. With the Corvettes that you’ve seen here, do they have fiberglass bodies like the street cars? So you wouldn’t do acid dipping with a Corvette, I guess.

Tommy Kendall: Eventually they transitioned to removable fiberglass and then carbon fiber bodies.

So all the [01:10:00] cars had fiberglass later on. I’m sorry, probably. Late 70s? When my dad did it, it was still unibody. It was, yeah. 82, 83, something like

CROWD: that. When you were talking about that performance equalization and all these formulas and this and that, I mean, it seemed like metal body race cars and fiberglass race cars would be, did they run in separate classes?

You had a minimum weight

Tommy Kendall: that everybody had to meet. But what the acid dipping would do is it would get the weight and you could put it down lower in the car.

CROWD: Lower the center of gravity? It

Tommy Kendall: lowers the center of gravity, yeah. And that’s They’re obsessive. I mean, they were pretty obsessive, obviously, from back then.

So, it continues today, the lengths they’ll go to. This is not TransAmp related, but I heard that Formula 1 had to pass a rule. Probably 15, 20 years ago now, prohibiting the teams from using depleted uranium as ballast because it was so much denser. You would think that common sense, that if it’s faster, someone will do it.

And if someone does it, everyone has to do it. [01:11:00] It’s

CROWD: a light way to get rid of the radioactive waste.

Lee Dykstra: We are, we’re getting lightweight stampings, so essentially we didn’t have to do the acid stamping as far as finger swipes, glass, all these sorts of things.

Tommy Kendall: Yeah, those, those beautiful blood morph cars. I remember one of the guys that owned one that you could like literally bend the deck lid with your, with your finger.

It was just really light, light gauge metal. I drove Parnelli’s car. Ford brought us both to the proving grounds in, I think, oh, 96 or 97. And Parnelli drove my car and I drove his car. The seat, it only came up to about here. Now, granted, I was taller than Parnelli, but my shoulder blades were over the seat.

And there was a lever down here that, there was, the seat belt went into this cord. And the core went down into this little mechanism, and when you flip this lever, it would unlock, so he could reach forward, and he could get to the switches, and maybe wipe the, uh, the windshield windows. And then he’d go back here, and lock it down.

I was thinking, that doesn’t seem terribly safe. [01:12:00] But, yeah, I drove that car, and I’m like, man. I had admiration for Cornello before that, but after driving that car, I said, man, what an absolute stud. And I’m just throwing out, he got out of my car, and he was, Let’s see, this was almost 20 years ago, so he was in his 60s.

He says, If I knew they were this easy to drive now, I’d still be driving. Go

CROWD: ahead. How many of you mentioned that you still own the, uh, one of the Berettas, that you have a plan to, uh, get without any penetrations or anything like that?

Tommy Kendall: I do. It’s funny. I, I had them all sucked away and, and my dad Called me and said, you got to get all this crap out of here.

And it was good, because it was like a barn find, but it was all my own stuff. So, I mean, I found some un I mean, I knew I had those cars. But, I mean, in terms of some trophies and posters and stuff like that. So, I shipped all of them. I have four, four mile race cars. My first five championships. And I shipped them all back to Dan Banks in Michigan.

Goal was to get them out for some vintage racing. But every time he calls me, [01:13:00] it’s at least 7, 500. So I said, just space these calls out. And I sound like a total jerk. Because I didn’t have to pay for anything when I was doing it. And I didn’t care what it cost. I’m like, what do you mean you don’t have to put new brake rotors on?

We need new brake rotors. And so I’m hoping to get some of them out. The first one that’s going to be out, the RX 7 that I won my first two GT titles with. Nobody has seen that. It’s the winningest RX 7 in history. No one has seen it in almost 30 years. So, it’ll be at Amelia Island next year in the show.