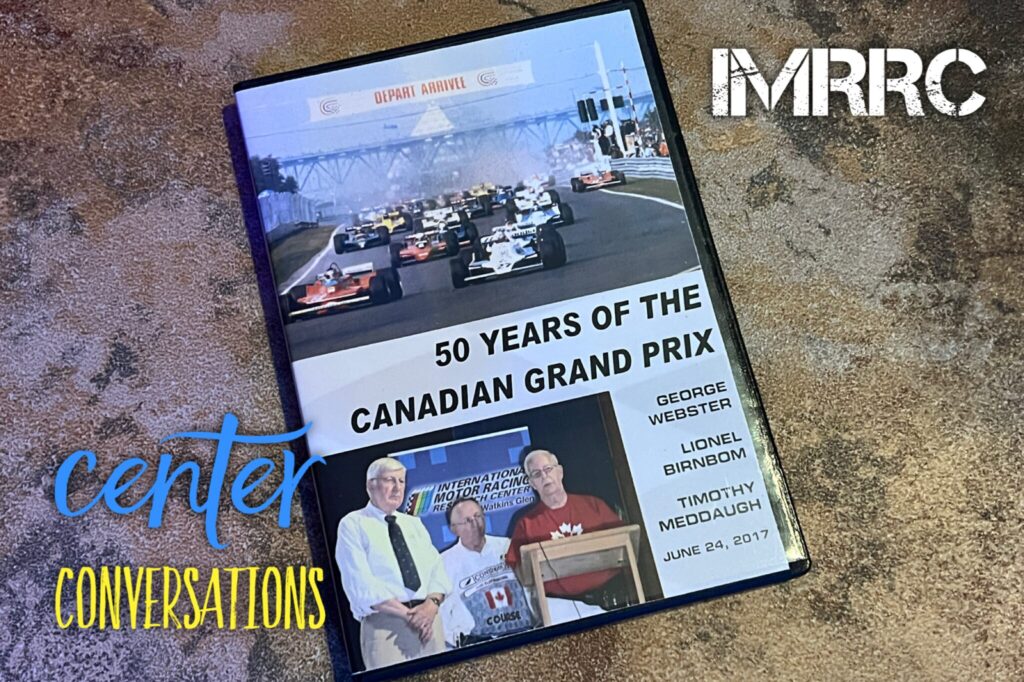

Today we’re going to learn about the exciting 50 years of Formula One racing at the Canadian Grand Prix, and we have three speakers with years of stories to tell. In order of appearance, we’re honored to be hearing from: George Webster, Lionel Birnbom, and Tim Meddaugh.

Part-1: George was a Canadian Automobile Sports Club appointee to the Stewards Committee for the Grand Prix races during the Mosport years and early Montreal years. He was Chief Steward, chairing the Committee of Race Stewards from 1977 through 1980. He has attended 71 Formula One Grand Prix.

George is a retired high school teacher from Oakville, Ontario. He’s been working part time as motorsports writer and photographer since the mid 1970s. And he has covered road racing, NASCAR, Cart, and Formula One for the publications including: Autosports Canada, PRN Ignition, National Speed Sport News, and the website goracing.com.

Part-2: of 50 years of Formula One racing at the Canadian Grand Prix. In order of appearance, we’re honored to be hearing from Lionel Birnbom and Tim Meddaugh.

Lionel is a self taught photojournalist of Ottawa, and he began attending motorsports events in the late 1950s. He was widely published in most major racing magazines and papers in Canada. Road and Track, Car and Driver, and Competition Press, Autosport and Motorsport, and many other hardcover, softcover racing books, including both of Pete Lyon’s Can Am books. He recently self published The Golden Years of Motorsports in Eastern Canada and the USA, a photographic journey from the late 1950s to the 1980s. It contains more than 2,100 photos.

Tim was a pit and paddock marshal as well as a flagger for four years of Mosport. He then worked as a flagger at every station in Montreal until his last race in 2012. Overall, he has worked at 65 Formula 1 races in Canada or the United States, including the first United States Grand Prix at Austin in 2012.

Credits

This episode is part of our HISTORY OF MOTORSPORTS SERIES and is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Transcript (Part-1)

[00:00:00] BreakFix’s History of Motorsports series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argettsinger family. My name is Tom Wiedemann, and I’m Executive Director at the Motor Racing Research Center.

Today we’re going to learn about the exciting 50 years of Formula One racing at the Canadian Grand Prix, and we have three speakers with years of stories to tell. In order of appearance, we’re honored to be hearing from George Webster, Lionel Birnbaum, and Tim Meadow. So let me start with George. George was a Canadian Automobile Sports Club appointee to the Stewards Committee for the Grand Prix races during the most part years of the early Montreal years.

He was Chief Steward, chairing the Committee of Race Stewards from 1977 through 1980. He has attended 71 Formula One Grand Prix. George is a retired high school teacher from Oakville, [00:01:00] Ontario. He’s been working part time as motor sports writer and photographer since the mid 1970s. And he has covered road racing.

NASCAR, kart, and Formula One racing for the publications, including Autosports Canada, PRN Ignition, National Speed Sport News, and the website goracing. com. So, ladies and gentlemen, please join me in welcoming our speakers, and we’ll start with George. So this year, we’re marking the 50th anniversary of the first Grand Prix of Canada.

That was held at Mosport in 1967. There’d been a race every year, this would have been the 51st running. But it’s actually only the 48th running because it was canceled three times in 19 75, 19 87 and 2009. Cancellation has been threatened two other times that I know of 2004 when the federal law prohibited tobacco sponsorship in the cars completely prohibited it.

And in 2017, this year, the organizers at Montreal had promised to do about $18 million worth of upgrades and had apparently done none of them. [00:02:00] And so that the race was under question. Now they. have been given a postponement for two years. 2019, they’re supposed to do those, that 18 million improvements.

So this year, the Canadian Post Office recognized the 50th anniversary of the commemorative set of stamps, honoring five GP winners, Jackie Stewart, Gilles Villeneuve, Erickson, Michael Schumacher, and Lewis Hamilton. All with the exception of Gilles, they were multiple winners of the Grand Prix. I think there would have been more appropriate subjects for them to recognize the Canadian Grand Prix, but I guess this is what they thought would sell.

So, I attended the first Grand Prix at Mosport in 67, and I was at the 48th running, uh, two weeks ago. I attended all eight GPs at Mosport, the next six in Montreal, and a few more since then. In all, I have attended over 70 Grand Prix, here and in Europe. Despite its European origins and identity, the Formula One Grand Prix of Canada has always been, without question, the premier auto racing event in Canada.

And there’s no other annual sporting event of any kind in Canada that has such an international reach. What might it [00:03:00] be? The Grey Cup? The Stanley Cup? The Brier? Only Canadians would know what that is, that’s curling. As for other race events in Canada, nearly all the other major… Auto racing events are visiting rounds of American based series.

By contrast, here in the United States, there are many annual race events which tend to overshadow the USGP, such as the Indy 500, the Daytona 500, 24 Hours of Daytona, and so on. 1967, 50 years ago. What do we remember? Well, here’s some things that come to my mind. It was Canada’s centennial year. We all remember Expo 67, which was staged in Montreal and on two islands.

Île Notre Dame, where the Grand Prix is held, was built as an artificial island completely. The other one was Île Saint Helens, was partly built. I’m from Toronto. The Maple Leafs won Stanley Cup that year. Ronald Reagan inaugurated as governor of California. That’s a long time ago. Probably remember that there were race rides that year in Detroit and many other U.

S. cities. The Beatles released their album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Band. In the movies we had Dustin Hoffman and The Graduate, Clint Eastman, and the movie A [00:04:00] Festival of Dollars. On television it was The Smothers Brothers. On Broadway it was Cabaret, and Hair was still off Broadway. But in our context, perhaps more significantly, was the movie Grand Prix was released late in 1966.

It was in Cinerama, which is like IMAX. Today, and it featured amazing in car racing footage, unlike anything we’d ever seen before. And it introduced the general public to Grand Prix racing, the circuits, the cars, the drivers. Some fictional and some real. So when the Grand Prix came to Motorsport in 1967, there was already a ready built, well informed fan base in place.

Pretty sports cars and their more humble economy sedans were very popular, and we lusted for the more expensive makes like Porsche, Jaguar, Mercedes. This was the foundation of the so called sports car movement in Canada as well as here. The number of sports car clubs in the 50s was exploding. The Canadian Automobile Sport Clubs, or CAC, was a federation formed of member clubs across the country, especially in Ontario and Quebec.

So CAC affiliated clubs had organized sports car races on the runways of former World War II air training [00:05:00] bases beginning in the early 1950s. There were at least five different airfield circuits that operated in Ontario in the pre most sport era. We got our news from magazines like Canada Track and Traffic and Road and Track.

Even though their long lead times meant that the racing news was pretty stale by the time we read about it. There were weekly papers like Competition Press and Motoring News, but few Canadians read either one of those. Companies like Castrol, Shell, and BP produced racing films, which the clubs borrowed to show at their meetings, and there was very limited television coverage of car racing at that time.

So the recent invasion of the Indy 500 by F1 stars, like Jack Graven, Clark, Gurney, Graham Hill, and Jackie Stewart, had given these drivers much more visibility. As we knew a lot about the recent history of sports car racing in Formula One, but we may not have been too up to date on the recent events of the current season.

With the large immigrant population, especially in Toronto, Montreal, we had a built in fan base of post war arrivals from Britain, Germany, and especially Italy. Watkins Dunn have been putting on the USGP here. Since 1961, and most sport, there have been professional races since its beginning in [00:06:00] 1961. The Players 200 and the Sports Car Canadian Grand Prix, and at San Jovita’s, we called it then, they also ran professional sports car races.

In 1966, both those circuits hosted rounds of the first year of the Can Am Series. Gerald Donaldson, who has become Canada’s premier Formula One rider, wrote a definitive history of the early years of the Canadian Grand Prix, and I found this book to be a valuable resource. The photos I’m using today have been scanned from contemporary publications.

Many of those photos are credited to Lionel, who you’re going to hear from next. And I know he’s going to be using some of the same photos I’m using in his presentation. And thanks to Bill Green for the use of his program collection, which I’ve made good use of. By 1967, we were ready to welcome a proper Formula One Grand Prix to Canada.

Early in the decade, there had been a couple unsuccessful attempts to get a Formula One race in Canada. One to be a championship event, and one to be a championship round. But those attempts failed. The 1967 event was approved as a one off event in recognition of our centennial year. Both Georgette wanted the event, but it went to Mosport.[00:07:00]

So here’s the starting lineup for the 67 race. There were 18 entries. There were two Canadians and two Americans in addition to Dan Gurney. That is, only 14 Formula One regulars, and few of those had proper three liter engines, as allowed by 1966 rules. The new Dulles 49, with the new Cosworth Ford DFB engine, had won the poll and the race in its inaugural race.

The Dutch GP a few weeks earlier. This engine was to revolutionize and dominate Formula One racing for the next several years. But I doubt many people at Motorsport had any concept of how significant this engine was, even though these Lotus cars proved to be the fastest to qualify. That’s the point I was making about the fact we got our news from Road and Track, which is much so years old sometimes.

The other potential winner was the Brabham Repco, the champion car from the previous year. It’s a light car with a reliable stock block V8 engine. Others like Ferrari, Maserati, and BRM had gone down the wrong track building big, heavy, and often unreliable engines. The rest of the car, the entries in the main were using bored out engine from the previous 1.

5 litre rules, trying to run in a 3 litre class, [00:08:00] or from the even older 2. 5 litre rules that ended in 1960. So here’s the starting grid. The two lotuses who are on the front row to the left there are out of frame. That’s Denny Holmes, Brabham, Repco in the front there. It was a rainy day, started in the rain, note the spray.

Also note that Clark is already three, four car lengths out ahead of everybody else. With Hill behind him and Holm off to the side there. Later in the race, here’s some more spray. That’s Gurney leading the eventual winner, Jack Brabham. Gurney ended up lapped down, so this is probably taken at the point when he was being lapped.

The two Lotus cars were the fastest, but they had troubles in this race. Notably, the ignition shorted out when the rain came down. And the Brabhams, who were on good gears, had a better pace when the surface was wet. Second half of the race, the rain came down quite heavily. And Lois’s were done for. Most of the drivers made pit stops to try to get dry goggles.

Only Jack Brabham had a relatively uneventful day. He cruised home to win by a margin of more than a full minute over his teammate Danny Holm. The only other driver to finish all 90 laps. [00:09:00] Journey was third, a lap down. There were 12 finishers, 5 DNFs. The two Brablins ended up winning, even though we consider them to be kind of underclass cars.

They had won the championship the previous year. They were to go on to win the championship in 67 as well. Best result for a Canadian driver went to Alpeze, who only completed 47 laps. Alpeze gets a lot of bad press. I remember Alpeze from when I got started in the late, latter part of the 50s. And in Ontario, he was a really well respected driver.

He drove MGA, MGA Twin Cam, MGB, Lotus 23, and was a successful driver. People tend to think he was over his head with his car. It was a car that had an old four cylinder Climax engine. I don’t think it was well prepared, and I think he just had a lot of bad luck. But it’s unfortunate because LPs, his name is mud when it comes to Formula One.

So it may not have been a classic race by any measure, but it was our Grand Prix. And it was our first F1 Grand Prix, and that makes [00:10:00] it iconic in the history of Canadian motorsport. Bob Hanna was one of the key figures, among many, in making this event a success. And he continued to play a key role as CESC’s Executive Director until its unfortunate demise in 1987.

He’s sort of Candace Cameron Argensinger. Cameron, of course, had many different important roles in the development of sports car racing in the U. S. here in Formula 1. And Bob was there right through 287. When CSE was booted, and he lost that role. Fortunately, he landed on his feet with another role. I’m gonna skip from there to Mont Tremblant and do the two years together.

Vinyl’s more familiar with these years than I am. Key thing was, up until then… CAC was not an ASN in its own right, only had the right as a affiliate of the RAC in Britain. And that’s why the racing colors were green, like Britain’s. There was a problem for Britain to get a second Grand Prix, even if it was in another continent.

So after the 1967 event, the FIA granted CAC full ASN status and the right to stage an annual Grand [00:11:00] Prix. And incidentally, at the same time, CAC changed its racing colors from green with white stripes to red with a white stripe. Racing colors kind of went out of style in those days. A lot of people aren’t even aware of that.

In this era of rapprochement between English and French communities in Canada, a decision was made to alternate the Grand Prix between Quebec and Ontario. That was happening in Britain between Brandon Satch and Silverstone, for example. So here’s the first race at Saint Jovit. Hosted the first Can Am race of all Can Am races in 1966.

Notice that they recycled the artwork from the year before. And the official name down at the bottom there is Surpix Mont Tremblant Saint Jovit. It had limited space in the paddock and the pits and limited vantage spots for the spectators. More importantly, it had a two lane road coming up from Montreal.

Jackie Eakes was driving for Ferrari that year. He crashed in practice and broke his leg. Our Prime Minister, Pierre Tudor, was a very popular Prime Minister, flew in by helicopter. I think that was exciting in itself. He waved the flag to start the race and he stayed engaged. to the end of the race. He [00:12:00] presented as a real fan.

Rint started from the pole in a Brabham Repco, but Chris Amon led the first 72 laps in his Ferrari. This is the only time when the cars had the high wings in Canada. And the 1967 champion, Denny Holm, starting from the third row, was the winner in McLaren Ford. I’m going to skip a year of Ford 1970, after a year back in most Ford.

where they put the picture of the new Tyrrell Ford double aught one. It was much anticipated, although nobody had ever seen one on a racetrack, on the cover. George Eaton, who is a sign of the Eaton department store family, the most important department store chain in Canada by far, bought a ride with BRM for a season and a bit, but he had limited success.

He finished 10th tier at St. Gervais, and that was his best ever result. By the way, Lance Stroll’s ninth place in this year’s Canadian GP was the best result ever for a Canadian driver, other than the two Villeneuves, Gilles and Jacques. Stewart in the Tyrrell showed up at the race, he qualified the pole he led for the first 31 laps, and he was motoring off into the [00:13:00] distance, says Donaldson.

On lap 32, he retired with a broken front stub axle. Remember, this was the great new car. The next two races here at the Glen and at the Mexican Grand Prix, he retired as well. There’s Ekes, 1980. He inherited the lead after Stewart retired, he’d run the race by 15 second margin over a Regazzoni and the other Ferrari.

Chris Amon in a March was the only other driver to finish in the lead lap. A year in between, 69, and then we jumped to 71 through 77 at Mosport. So this is the 69 interstitial race at Mosport. Jackie Eakes won the pole in his Bram Ford, while Jackie Stewart was fourth fastest in his Macra car with a Ford engine.

Eakes led from the start, but Stewart had caught him by the fifth lap, and he took the lead. After that, Eakes hounded Stewart, and on lap 33 of the 90 lap race, Eakes made an impossible move to duck inside Stewart, coming over the crest into the second turn. If you know most sport at all, that’s it. It’s the trickiest possible corner, and nobody should try to make this [00:14:00] maneuver, coming over the crest into two.

They collided, Stewart spun off and out of the race, but Ekes kept on going. Not a very popular guy. He won the race by a margin of 36 seconds over Jack Brabham in the other Brabham car. Rint in a Lotus was the only other driver to finish in the lead lap. So after this, the GP returned to St. Gervais in 70, and then it came back to Movesport.

in 71. Notice that the players still like recycling the artwork. And also notice the name, Players Grand Prix Canada. To me that’s significant because that’s not English, it’s not French. In French it would be Grand Prix du Canada Players. But it should be Grand Prix du Canada. And in English they call it Grand Prix of Canada to try to have the parallelism.

So I think this was an attempt to just fudge over that. 71, my biggest memory, was something I never saw. I was down at corner 5. There was a driver named Wayne Kelly who was, I guess, from the Ottawa area, who was a very popular driver and was, looked destined for stardom, and at least was in Canada. He was killed in an on track accident during the [00:15:00] Formula Ford race when he came over the crest between corners 1 and 2, ran into an ambulance, parked on the track, and was killed instantly.

When I questioned, do we really need these full course yellows on a road course, this instant would be one of the major… arguments early on to say, we’ve got to do something. Something is full course yellow. I hate those full course yellows on a road course, but I think this Wayne Kelly incident was one of the ones that is in the history of that.

So there was a long delay under Ontario law. The coroner had to be dispatched and he had to do whatever he does. By the time we were ready to start the Grand Prix, it started raining. So then they had a delay over that, but over two hours before the race got started. Wasn’t such a big problem in the pre television days.

By lap 60 of the 80 laps, the rain had turned to fog and darkness. So the race was flagged off after just 64 laps. Stewart and Peterson had shared the lead, but Stewart led the final 33 laps to take the checker. Peterson was second in a march, while Mark Donohue was third. Here’s my friend George Eaton again.

Finished 15th, and it was his last race with [00:16:00] BRM. And kind of his last race ever. By this time, he’d pretty well run through his inheritance, I believe. The department store, by the way, is long since defunct. It’s not just George Eaton that’s lost out, but he’d used his inheritance in racing. Maybe it was a good idea, because I guess the rest of the family just lost it through bankruptcy of the company.

472. Back at MoSport, CAC made the decision not to return to San Gervino as originally planned. It had been proved to be an unviable business proposition. Not enough spectators could get up that two lane road on race day. From my perspective, which was as a member of the National Executive, I see that that decision was essentially a CAC decision, even though most people try to place the blame elsewhere.

Ultimately, CAC just pulled the plug and said. We have lost a pile of money, whether players bailed them out or whether they had to bail themselves out. But CASC was on the hook for a huge amount of money and never went back to San Jovi. So CASC found a permanent home at Mosport and came [00:17:00] back in 72.

Publication was produced, I guess after the event. This is a driver’s meeting and I find it interesting partly ’cause I recognize most of the people, not just the drivers, but friends of mine are in that picture as well. This is at the foot of the tower as you go into the control towers. Anybody who wandered along could kind of cozy up at the back and listen in to the driver’s meeting.

So this race was also delayed by Fog Peterson led Stewart had start. Stewart had started from the second row, but after just three laps, he got passed for the lead and drove off in the distance that he won the race. Peterson continued to drive in his dramatic style, but he collided with Graham Hill, who he was laughing, and ended his day.

Peter Revson, who was a rookie that year in Formula One, finished second in the Yardley McLaren. In those days, you know, you didn’t have these half a second or three second gaps. Forty eight seconds back to second place. Aholm was third, also in McLaren. 1973. Interesting year. It was wet at the start, and I was sitting in the grandstand across from the pits as a spectator.

And the thing that struck [00:18:00] me most of all was this guy who started on the fourth row, dropped the flag and he’s gone, right into the first corner. I think he led into the first corner, Nicky Lauda, in his, I think his second year in Formula 1, first year with BRM. He did a lot better with DRM than George Eaton did.

Part of it had to do with the fact that they were on Firestone tires and a lot of the others were on Goodyears, and the Firestone rain tires seemed to be superior. In the wake of some serious accidents which had been inadequate rescue procedures, for example, the Roger Williamson fatality at Zandvoort earlier that year, the responsible officials had been talking about using a full course yellow in a Grand Prix for some time, and they had actually made a test run at an earlier event.

But this time it actually came to pass. Schecter and Saveir tried to run side by side down into turn two. Remember that with Eeks and Stewart? And Savert was crashed out of the race, check to continue. This was Savert’s final race. Watkins Glen people know this. 1973, Savert here was killed in practice. So he never [00:19:00] started the race here.

But this accident with the service vehicles that were out partially blocked the track, so they called out Effie Weitz’s in the pace car. Unfortunately, in that era of handmade lap charts, no one was quite sure who the leader was after most of the cars had pitted to change off their rain tires. So they told Eppie to pick up Houghton Ganley, a little while ago they thought he was the leader, I think he was a lap down.

So he came out in the middle of the lap. If the pace car comes out in the middle of the pack, the guys who were in front come around and make up a lap, and the people who were behind are trapped. So Fittipaldi was trapped behind Ganley, and these other guys go brrrrrrrr, and they come around. But the key people, who were the race control people, weren’t sure or didn’t know how to fix it.

After the pace car was called in, the racing resumed, confusion continued. So, here’s the scoreboard at lap 80, at the race. That’s Fittipaldi, number one. Number two is Ganley. Number three is Revson. Number four is Beltwaz. Understandably, Colin Chapman thought his guy had won the race. He runs out in the [00:20:00] track, throws his hat up in the air, but there was no checker.

Stardew Way, standing there, standing there. Finally, this group of Ganley, Halewood, Revson, and Hunt come around, and out comes the checker. And so they ushered these three guys, Fittipaldi, Rebson, and Oliver, to the podium, and they stood there with bemused expressions on their face, and the trophy was handed to Rebson, and they finally got a new Maple Leaf trophy there.

So, in the hours that followed, the lab scorers were able to recheck their work using the tapes that had been marked with the car numbers as they passed. It takes a few moments before the information written on the tapes is transferred to the actual lab chart. But it is an accurate, if a little bit slow, method.

So in the end, after they went through some hours of double checking, triple checking, they verified that Reveson was the race winner, Fittipaldi was second, and Oliver third. So it appears that when they took them to the podium, they already had a pretty good, rough version of this hand lap chart based on the tapes.

I think there’s about a maximum delay [00:21:00] in that process of about a lap. So they knew, but nobody was going to believe them until they went. Spent hours doing it. Deltas was fourth, and Ganley was sixth. So it’s no surprise that in F1 they got cold feet about the pace car. This is 73, and it wasn’t until 93 that they finally came back and established what we now know as the safety car procedure.

And of course, computerized lap scoring had been established for a long time by then. So you have, we all know now that the lap score, as soon as the car crosses the line, sometimes, I find it confusing, sometimes they are updating halfway around the lap. So, 1974, this is significant in that we have Andretti in a Parnelli, American made car, and Donahue in a Penske, another American car.

There’s the podium with Fittipaldi, the winner, Peterson and, uh, Reconzoni. He left here tied in championship points with Reconzoni, who had finished in second place. Fittipaldi finished fourth here two weeks later, but that was good enough to give him the title. 1975 is, nothing happened, but everything [00:22:00] happened.

And the iconic points in the history of the Canadian Grand Prix, this is one of the big ones. So there was no Grand Prix. Bernie Ecclestone, who had come in as the owner of the Brabham team, had talked to all the garages, that’s everybody, basically everybody but Ferrari, into having him negotiate a collective agreement on their behalf.

He was starting to turn the screw. He was involved in negotiations with both Moorsport and Watkins Glen. In August of 75. He set a deadline. This is Bernie’s stuff. There’s a deadline. That’s it. No compromises. I don’t know what was going on, but the most board people dithered a little bit and didn’t meet the midnight deadline.

Malcurry saw what was going to happen and decided he would accept Bernie’s terms. So he accepted Bernie’s terms. Most board people got up the next morning and Bernie said, Well, there’s going to be a Grand Prix at Watkins Glen and there’s not going to be a Grand Prix at most boards. Tough. I think that’s exactly what Bernie wanted.

Because he only lost one date off the calendar, but he had an object lesson that stood for every other Grand Prix organizer he was negotiating with. [00:23:00] Do what I say, or you’re screwed. I’m not going to compromise. Anybody else would have said, they’d come in the next morning and said, Sorry, we, we were confused.

We’ll sign now. Where do I sign? If you’re buying a car, you come in the next day, and you said, Yeah, I decided that was the price you’re, where do I sign? He would have said, Yeah, fine, you got a car. Bernie said, Screw you. Because Mosport was committed to run the date, and they advertised it, and they had all the sport races organized, they still ran the race, whether it’s the Grand Prix, and they call it the Grand Prix.

Terrible weather. One of the worst days of weather I’ve seen for a race event. So, we get to 76. At the start, Peterson is leading Hunt, but notice that they’ve got the low air box, and not the high air box. Hunt took the lead on the 9th lap, and basically drove home. General Donaldson wrote, Hunt won in convincing style.

But there was a great interest in Nicky Lauda, the leader of the World Championship. in only his second race after his near fatal Nürburgring crash. He finished 8th between Carlos Pace, who had a wild entanglement with Clay Ragazzoni in front of the pits, three laps from the end [00:24:00] of the race. So I was one of the stewards for that event, and Bernie decided he was going to protest that Ragazzoni had caused that crash, and hurt his driver’s chances, and so on.

Ragazzoni only spoke Italian in the meeting. So we had to translate everything, but he sometimes would forget and answer before the question was translated. So, anyway, we ruled that this was a racing incident, but… It’s a pretty common occurrence that he came in the corner 10 and you over cook it. It gets loose and you go wham, straight into the pit wall or almost into it.

Bobby Rahall had a really big crash there in the Can Am Cup. Anyway, we said, no, we’re not going to play your game, Bernie. You deal with that. It had something to do also, I think, with who was contracted who the following years. So, 77 was the final year at MoSport. Labatt’s had already made the decision to go to another venue the following year.

Aside from that, I don’t think there would have ever been another Grand Prix at Mostport after 77, even if they hadn’t already made the decision. Because on Friday, Ian Ashley took off the back straight, and I think he got about as high as the ceiling before he [00:25:00] landed. He landed, hit the top of the television tower.

Turned out that the rescue procedures… were solely lacking. Big point they made was that they had promised they would have a helicopter ambulance on site and they didn’t. You know, you got a couple marshals. Marshals are not trained to deal with an incident like that. You know, they’re not expected to deal with that.

But basically they went in there with hacksaws and their team, their crew rescued them. Terrible, terrible. People were really, really upset that. So, that was enough. So the next day, Yoke and Moss, coming out of 1 up here, overcooks it, hits guardrail, guardrail falls over. They look at the posts and they’re rotten.

I think that probably the driver’s back of the garage was in. Are we gonna run? Are we gonna pack it in now? So there was a lot, a lot of talk. I’ve read a couple different reports of how this transpired. What I do know, cause I was in the tower, from my vantage point in the tower, I do know that the clerk of the course, Paul Cook, agreed to a request to drive James Hunt around the [00:26:00] track and he interviewed Marshalls.

What are your qualifications? What is your experience? As if that had something to do with James Hunt. I was livid. I was livid. As far as I’m concerned, Paul Cook should have said to him, The FIA has inspected this course and approved it. If you have a beef, talk to the FIA. You can’t wait to talk to the FIA, talk to the stewards.

But… The fallout would have been that the track would never have been approved again for an F1 course. Little known fact, and I was in the tower, and I was in the tower during lunch hour when there was hardly anybody there. The telephone communication system was, I say, unreliable in my notes. It was out.

There was no communication system. But the whole of lunch hour, from the time we stopped, whatever we were doing, before lunch, to about 15 minutes before the green for the Formula One race, we had no telephone communications. I was the chief steward, and so I was rehearsing my lines to say, there will be no race.

You will not drop the green flag. Fortunately, I think it’s fortunate, I didn’t have to do that. I think everybody dropped the ball, not [00:27:00] including the FIA. I don’t think they should have approved it. If the course was that bad, they shouldn’t have approved it. And they should have an inspector there for the race.

On the bright side, Gilles Villeneuve had been signed with McLaren. And he went to Silverstone in 77 in the end of June, July. And he had a really good run. Really excellent run. He finished 11th, but had he not pitted because he thought his car was overheating, he probably would have finished 7th. Really excellent run.

Better than Jokerman, his teammate at that time. He had a contract. McLaren had also tested Patrick Tambay, who was a good driver. They went with Tambay for whatever reason. So here’s Villeneuve, just out of luck, just beach. So Chris Amon, who had been responsible for the Dallara Wolf Formula One car in 77 the same year, he called up Enzo Ferrari, who he worked with, who he’d driven for.

And said, hire Villeneuve. And they did. They hired him. With a full time contract as of 78. So when they got to Canada in 77, they had a third car for him. This was his debut with Ferrari. Right there, that 21 car. [00:28:00] Lauda had clinched the championship the week before here, and he was going to go to another team.

He was going to go to Brabham. As I understand it, they unceremoniously fired his mechanic here. Because he was going with him to Brabham, So Ferrari, before they left the track here, said Forget it, you’re done. So Lauda was totally pissed, and he said, I’m not, I’m done. That’s it. And he says, and on top of that, I’m not gonna run, you’re running three cars, you’re not gonna provide proper support.

I think that was just bullshit. But anyway, he said that. You’re running three cars, I’m not gonna run them if you’re running three cars. So he didn’t show up. Ferrari tried to protest Lauda because he had been entered in the event and then withdrawn without giving enough notice. Well, the team owner can’t protest his own driver.

I don’t think that’s possible. Anyway, that’s what we thought. We couldn’t see any way that Ferrari could protest Lauda because Ferrari was the entrant, not Lauda. They were really protesting themselves. So we just said, forget that. Villeneuve was running about ninth. He spun off an oil and turned ninth, and he retired.

He had finished [00:29:00] 11th in the McLaren at Silverstone. This is 77. Okay, that marshal on the ground, his name is Ernie Strong. So I was in the tower, Hunt was coming around, trying to catch Andretti, who was leading. He came up past Moss, I still can’t quite figure out, I think Moss was a lap down, but he finished in the lead lap, so I don’t know how that happened.

Anyway, he came by to go by Moss, and there was a miscommunication about which side he should have gone on, and he got knocked off, he hit the guardrail pretty heavily, and was kind of trapped in. He had to leave a shoe behind to get out. Ernie went, pull him out. Hunt is out. He’s presumably a bit dazed if he’s been, that had much impact.

And he starts to walk towards the truck. Eddie Marshall’s trained to know that driver might be confused when he gets out of the car. You’ve got to really kind of watch that they don’t do something stupid. When they start to walk towards the track, you’re going to restrain them. And if that doesn’t work, you’re going to restrain them a bit stronger.

Ernie goes to stop them from walking towards the track. I now know, from reading the biographies, that Hunt is tremendously volatile. So he just [00:30:00] swings. Tremendous haymen here. Knocks Ernie strong to the ground. Flattened to the ground. As stewards, after the race we dealt with it, Hunt was long gone, but we unanimously agreed to give him the maximum fine.

It wasn’t much, it was a thousand Swiss francs, which was kind of a joke now. That’s the worst we could do to him. We were really upset about it. So anyways, it turned out Andretti was leading 78 of the laps, but he stopped for lack of oil pressure. Jody Schechter, who was driving this Wolf car, which was running in Canadian livery.

Walter Wolf’s, uh, Austrian who made a lot of money hauling materials at Expo 67. So we were pretty happy that a Canadian car had won that race. Schechter had won twice before in that car. Even though he had seven retirements that year, he finished second behind Lauda in the championship standings. So, if I’d bought a program that year, which I didn’t, I would have discovered this graphic in the program, which said, next year’s race is at Toronto’s Exhibition Place.

That’s where the Indy, now called Honda Indy, is held. And it’s more or less the layout. So that was Labatt’s plan, was they were going to go to Toronto, and they were going to [00:31:00] have it there. There’d been an earlier plan to do that by a different promoter, and the people from Most Board had raised so much hell that they got the locals all riled up, and they convinced the councillors to vote it down.

So they come back here about five years later, and they want to run their own race, the Grand Prix. Well, most people remembered all those horror stories that had been told, and they convinced their councillors to turn it down. The story goes, the next day, Jean Drapeau, Montreal’s mayor, got on the phone to LeMats and said, Well, let’s go to Montreal.

Now, there’s a lot of legend in that. But, no question, it went to Montreal. It’s the same circuit, two different names, obviously it became Gilles Villeneuve after his death, and it’s still there this year. And it looks like it’s going to be there for quite a while, despite the little glitches. The contract with, now called F1 Group, Formula One Group, has been extended to 2029, and between the three levels of government, a promise of 100 million, which sounds like a lot, but in the way over that many years, 15 years, it’s actually not that much.

Here’s the site. of Expo 67. And [00:32:00] that’s where they built the track. Most of the buildings, if not all of them, are still there. The track portion that… This is the rowing basin back here. This is where the pits are now. This is kind of a lake that’s still there. This building is now the casino. That was the French Pavilion.

This was the Quebec Pavilion. It’s now been seemingly converted to be an extension of the casino. Pretty well everything else you see, with the exception of the U. S. Pavilion, this dome, and the bridge itself, is gone. Anyway, the track came along here, it went back up around this lake, and it came back along here.

under this bridge, deked like that, came up around, these buildings were pretty well gone, and then came around, back like that. So Roger Perk, he was a CASC officer and he was commissioned to find a location of the new circuit, and the obvious choice was Ile Notre Dame, and that’s an artificial island built for Expo 67.

This whole island here was artificial. So it was used also for Expo 67 and the 76 Olympics for the rowing. This location has proven to be an ideal one for the Canadian Grand [00:33:00] Prix. And even though I’m not a big admirer of Roger Peart, I think this is a major achievement on his part, and I think that we can all be proud of his achievement and congratulate him for it.

78. Andretti had won the championship that year with the Revolutionary Ground Effects Lotus 79. I meant to say this earlier, but the Cosworth engine made the 70s the greatest period in Formula 1 because everybody had the same engine, it was competitive, and even though there were a couple other engines.

The Cosworth engine was a winning engine, so many teams were very closely matched and there were lots of different winners. Ground effects was the next revolution. Lotus came up with it first, Andretti won in 79, and he’d already won the championship by then. However, you may also remember that when Andretti won the championship, he won it after Ronnie Peterson died as a result of an accident at Mons in the preceding race.

Andretti became immediately the champion, because Peterson was no longer a competitor. They got Jean Pierre Gerrier to drive the Peterson car, and he put it right in the front row with Jody Schechter there. [00:34:00] But here’s Gilles. This is his first year, full year with Ferrari. He’s in the second row, the third fastest car.

And Andretti, his car never ran properly. He’s way back. Gerrier and Schechter come firing off the front row, number 12 in the middle, the next row back, there’s Villeneuve. Jones got ahead of Gerrier, but he had a slow puncture, which moved Gerrier up to the lead. Schechter was in second, Villeneuve was third.

Mid race, Villeneuve passed Schechter to take second. That was like the second coming, when he got into second place. Huge roar. Jerry continued, was dominant, but he retired with an oil link and it left Bill Newb in no opposition. He continued to take his first career win in his home race ahead of Schechter with Royderman running third.

Nobody cares that if Jerry hadn’t dropped out that he would have won. Bill Newb won the race, the greatest Canadian racing hero ever, engraved in stone forever. I just say in my notes, and the crowd went wild. It was unbelievable. It was unbelievable. Before he came around the next time, on the Kulaf Lab, that fence was [00:35:00] down.

Totally down. And the crowd was coming straight out on the edge of the track. They knew the car was still on the track. They came out to the edge of the track. So there’s the results. The only one that counts is Villeneuve won. That’s it. We don’t care about anything else. Here’s my picture, which shows Gilles, the Prime Minister, and the man in the hat, who’s sort of responsible for it all, Jean Drapeau, the Mayor of Montreal.

Very controversially, all of these. He’d made Expo 67 happen. The Olympics end this race. Outsiders from outside Montreal thought, Oh, what, how much money is spent? How much of my money has gone into this? In Olympic Stadium, they took 30 years to pay for, and so on. But I think in Montreal, he was always a beloved figure.

He said that Expo 67 can no more lose money than I can get pregnant. Well, it lost money big time. Here’s the magazine I was writing for, Autosport Canada, and it’s a composite picture. But to me, that kind of represents the iconic form of the Canadian Grand Prix. of the [00:36:00] 78th Grand Prix of Villeneuve, Montreal, U.

S. Dome, the skyline in the background. This is sort of the impression that’s imprinted. Pete Lyons wrote in the magazine he was writing for the day, the Disney esque victory of Villeneuve must have cemented the future of the GP in the minds of Quebecois for many years to come. How true. So the development of the circuit on Ile d’Octodame was the right track in the right place.

Right up against the city. Despite changing ideas of what F1 track should be like, this track has aged well over the years, and Montreal has become a destination city for F1 fans. And with Gilles popular win in 78 and his success in subsequent years, although he never won the championship, of course, he has indeed made the Grand Prix of Montreal a great piece of Canadian heritage.

And this… 78 Race is the iconic Canadian Grand Prix. Jumping ahead this to 87, there was no race in 87. This had to do with conflict over sponsorship. [00:37:00] Lava had been the sponsor and signed a contract with C A S C. Somebody else had signed a contract with Molson. Bernie wanted to go with Molson ’cause there was more money I think.

So he refused to bring the cars to Montreal when there was Le Mans sponsorship. There was no race. There was a race in 88 under Molson sponsorship. Some other good came from this. CAC was disenfranchised, and a new ASN was created. We have an ASN that’s basically Bernie’s puppet. No other really fair way of explaining it.

ASN we have, Roger Pert is the chair, pardon my impotency towards him, is basically Bernie’s puppet. And a man by the name of Terry Lovell, who wrote a book called Bernie’s Game, he says, the FIA arranged the setting up of what was effectively his own Bernie’s. National Sporting Authority. And nothing has changed.

I don’t think even with Bernie retiring from Formula One management, I think he still controls the ASM. I won’t say any more for fear of being accused of libel. I could say some more libelous things than that. A good part of us was Bernie got what he [00:38:00] wanted, and he wanted to have a race in Montreal. And he wanted to make a lot of money out of it, and so everybody’s happy but me.

And the CSE loyalists. One of the things that we did get, they moved the pits. So, during 87, when there was no race going on, they built the new pit complex, which was a much better location. The only problem with that was the pit exit came out kind of awkwardly in the middle of that straight, which was a bad idea.

I don’t know quite how that happened. Those are the years that I was most involved. I, my involvement. Really, after Gilles was killed, it was Formula One, for a number of reasons, became much less. There’s been a lot of history since then. That’s my version of it. And I’m going to introduce Lionel, who’s going to come up and take over for me.

This episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center. Its charter is to collect, share, and preserve the history of motorsports, spanning continents, eras, and race series. The center’s collection embodies the speed, [00:39:00] drama, and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world.

The Center welcomes serious researchers and casual fans alike to share stories of race drivers, race series, and race cars captured on their shelves and walls and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events. To learn more about the Center, visit www. racingarchives.

org. This episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The SAH actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers. Organizational records, print ephemera, and images to safeguard, as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding of motorized wheeled land transportation through the modern age and into the future.

For more information about the SAH, visit www. autohistory. org.

We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Brake Fix Podcast brought to you by Grand Touring [00:40:00] Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at GrandTouringMotorsports. And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article at GTMotorsports.

org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as 2. 50 a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional Pit Stop minisodes, and other VIP goodies.

As well as keeping our team of creators fed on their strict diet of fig Newtons, gumby bears, and monster. So consider signing up for Patreon today at www. patreon. com forward slash GT motorsports, and remember without you, none of this would be possible.[00:41:00]

Transcript (Part-2)

[00:00:00] BreakFix’s History of Motorsports series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argettsinger family. My name is Tom Wiedemann, and I’m Executive Director at the Motor Racing Research Center.

Today we’re going to learn about the exciting 50 years of Formula One racing at the Canadian Grand Prix. In order of appearance, we’re honored to be hearing from Lionel Birnbaum and Tim Meadow. Lionel is a self taught photojournalist of Ottawa, and he began attending motorsports events in the late 1950s.

He was widely published in most major racing magazines and papers in Canada. Road and Track, Car and Driver, and Competition Press in the U. S., Autosport and Motorsport, and many other hardcover, softcover racing books, including both of Pete Lyon’s Can Am books. He recently self published The [00:01:00] Golden Years of Motorsports.

In Eastern Canada and the USA, a photographic journey from the late 1950s to the 1980s. It contains more than 2, 100 photos. Thank you, George, for an excellent presentation. And I would like to thank Glenda Gephardt and Tom Wiedemann of the IMRRC for inviting me to be a panelist on this prestigious discussion group celebrating 50 years of the Canadian Grand Prix.

And I mentioned George’s excellent presentation. As he indicated, many of the photos used in his discussion were photos taken by yours truly, and published in Jerry Donaldson’s excellent book, The Grand Prix of Canada, that covers the years 1967 to 1983. In fact, I’m very proud that of the 162 photos in the book, 50 were mine.

I became interested in cars in the mid 1950s. With the emphasis [00:02:00] on sports cars and racing. Road Track, Car Driver, and Competition Press were the Bibles in those days. And I still have more than 50 years of each of Road Track and Car Driver, much to the chagrin of my wife, Melanie, in the audience. Born in Montreal, my developing passion in sports cars led me to the sports car clubs, and specifically the Montreal MG Car Club, as it was the most focused on organizing races.

Not being able to afford to race, I quickly realized the next best thing to be in the thick of things was to become a racing journalist and photographer. It got me into the pits, as well as right up to the edge of the pavement of the track. Pure heaven, and I didn’t have to pay for an entry ticket. After several years of writing letters to racing newspapers and magazines, a few editors began to say yes, and some of my photos and reports were eventually [00:03:00] published.

My career as a racing journalist and photographer was launched. However, this led to my next epiphany. That although I loved the sport, the cars, the people, and the travel involved in racing, the chances of earning a living from the sport were very slim. I therefore became a professional accountant, and it solved two problems at once.

Namely, I could earn a steady, decent living, and also afford to indulge my passion. Born in Montreal and having lived there for 36 years, I was acutely aware of the constant rivalry between Montreal and Toronto, or, more broadly, the provinces of Quebec and Ontario. Whether it was our NHL hockey teams, pro football teams, Major League Baseball teams, and of course, sports car racing and the tracks.

Once they took to a sport, the French Canadians of the province of Quebec were very passionate about it, [00:04:00] and the relevant excellent stars that they developed. This year we’re marking the 50th anniversary of Formula 1 in Canada, and the first one having taken place in 1967. That year was also the 100th anniversary, or centennial, of the founding of Canada as a nation.

The 1967 celebrations of that milestone included Expo 67, the World’s Fair in Montreal that George mentioned many times, wall to wall festivals, parties, and unbridled joy and happiness throughout the city of Montreal. What a stark contrast to today’s world. Mosport is located about 60 miles east of Toronto, and was built in 1961, quickly became the leading purpose built road racing track in Canada.

In 64, it was Montreal’s turn, and the construction of Le Circuit Mont Tremblant, situated amongst the beautiful ski hills in [00:05:00] the Laurentian Mountains, was built 90 miles north of Montreal. The 67th Centennial, as it approached, the topic in the sports card clubs and CASC, the Canadian governing body of the sport, was to get on the calendar of the World Championship, or F1.

What better time to have the first F1 in Canada than in its centennial year? The lobbying and politicking between Mosport and Mont Tremblant was fierce, and eventually the FIA granted the first ever Canadian Grand Prix for F1 cars to Mosport in 1967. Mont Tremblant would get the race the following year, and in theory the two tracks would hold the Grand Prix in alternate years.

Reality and many factors soon set in, which George covered quite well. And unfortunately, Mont Tremblant and Mosport faded out of the picture. This was the [00:06:00] beginning years of my career as a photojournalist for racing and cars. A good friend of mine in Montreal was a chap called Bob McGregor. If not the first, possibly one of the very first to have a network show that went right across the country in Canada on radio.

It was 30 minutes of sports car racing and news and car road testing every Monday at about 6. 30 Monday night. He would have correspondents from throughout Canada, the States, and Europe reporting on all the major events. Bob, he called up Rolls Royce in Montreal one day and said, I’d like to do a road test of your car.

Can I get one? Somehow they foolishly agreed. And that particular weekend, much to the chagrin of Rolls Royce, they didn’t realize the car would be going to Watkins Glen for its U. S. Grand Prix. About 50 miles out of Montreal, Bob invited me along for the [00:07:00] ride, and I said, sure, why not? Bob got tired of driving it.

He said, this is a pile of crap. Lionel, why don’t you take the wheel? Sure, thank you. And I drove the rest of the way to the Glen. And as we’re coming down Highway 14 from Geneva, I pulled over the side of the road. I said, Bob, I want you to get into the back seat on the passenger side. No, Lionel, I’m not.

Bob, do it. He listened to me. He didn’t know what I was going to come up with, but it was going to be some fun. The Glenn Motor Court, as probably most of you know, is on the hill coming into town here in the Glenn and was one of the centers of F1 racing throughout the years. The teams would book it this year for next year, completely sold out a year in advance.

I drove up in the driveway of the entrance to the Glenn Motor Court. Jumped out of the car of gorgeous, gorgeous burgundy with the tan leather interior and went around to the rear [00:08:00] door, opened it for Bob to get out. For those of you that know it, there’s a little bit of a driveway that comes in right at the front door of the office.

And immediately next to it is a great big picture window of the office. Naturally this car got a bit of attention as we rolled up and my role of getting out and opening the door for Bob sort of enhanced it a bit. And he went into the office and said, I would like a room for tonight. Plain dumb that the Grand Prix was on that weekend.

They fell over themselves apologizing that the place was full. They must have spent over an hour on the phone calling every available hotel, motel, B& B within a hundred miles of here. And eventually found a place for us. We then drove into town. Found a parking spot on Franklin Street, which was amazing.

Parked the car, and Bob took his tape recorder out, standing beside the car, doing radio interviews, and for some reason, the only people interviewed were [00:09:00] these very cute, young looking girls. Thank you, Rolls Royce. From there, this is the aerial view of Mosport in 1973 at the Can Am, and you can see basically the outline of the track.

And this is the Mont Tremblant aerial view, the actual inaugural Can Am in 66. Now, there’s an interesting story to this aerial view. The promoters hired a helicopter for the press to take them up and take aerial views of the track. The pilot tried to be very obliging and took off the passenger door of the helicopter.

As we lifted off, I’d never been in a helicopter in my life, but I said, wow, this is fantastic. He went around the track a few times, and we were talking back and forth. He kept asking me where would I like to take the pictures from, where to shoot, how to position the helicopter. And he got to the end of the track, and just hovered at the hairpin at the end, and tilted the [00:10:00] helicopter a good 30 degrees, so I could take my picture.

I was holding on to the frame of the doorless opening with one hand, my two feet braced against the dead pedals, and clicking away with the camera with my free hand. I’m very fortunate, I don’t have a fear of heights. This is Graham Hill, spun out in the wet, got out of the car, and started pushing it down the track, jumped in, and somehow got it restarted.

An event in the rain that you’ll never see today. The drivers in those days were very approachable. You could go up to the drivers, whether you’re pressed or not. Nobody was a prima donna. This was an image right here in Watkins Glen at the old pits. Joe Bonnier on the left, Roy Salvadori on the right. And they were having a casual game of cards in between qualifying and practice and whatever.

1960. 61, the card game continues. You’d never see [00:11:00] this today. John Surtees became one of my favorite people in motor racing. In 1965, John had a horrendous accident in a Lola T70, the pre Can Am car at Mosport. It was life threatening. Miraculously, he recovered before the Formula One season started in 1966.

And the inaugural Can Am at Mont Tremblant was September of 66, a year after this horrendous accident. I was out, as usual, around the track shooting. My then wife was on top of the control tower at Mont Tremblant for VIP spectators and was standing next to another lady during this practice session and qualifying and she just said, not knowing who this person was, Isn’t it wonderful to see John back in a car again?

The other lady turned to her and said, Thank you. And my former wife [00:12:00] didn’t know what to take from that and said, what do you mean? Well, I’m Pat Surtees. The rest of the afternoon, they conversed back and forth. And at the end of the afternoon, when I got back from shooting on the track, I came back to the pit area.

Met my former wife there. And she said, I want you to meet somebody. That somebody turned out to be John Surtees. He was the most humble man. The most ferocious man behind the wheel. And yet, he was a complete gentleman. And from that point on, every race that I went to that he was at, I made a point of going to say hello to him.

Whether it was a Can Am, whether it was a Formula One, or anything else. Fast forward to 1987. My new wife, who’s in the audience, And I decided we’re taking a vacation trip to England. About a week or two weeks before that, it was one of these London show tours that you bought a week’s package and everything was arranged.

But we were gonna add on [00:13:00] about ten days prior to that week of just touring around the countryside. I called up John. I said, You probably don’t remember me. I’m sure you see hundreds, if not thousands, of press people and photographers over the year. But I was at Mont Tremblant, Mosport, and Watkins Glen.

Spoke to you quite often. We’re coming over to England for a vacation. If it’s at all possible, I’d love to stop by, have a cup of tea with you and my wife. And no photography, no story, no interviews, nothing. Just a personal chat. He said, by all means, give me a call when you land here and I’ll tell you what’s going on for my day.

An overnight flight from Montreal. We landed about 5 or 6 o’clock in the morning, got our rental car. Fell asleep in a parking lot somewhere and about 9 o’clock woke up and I called John. We’ve arrived, we’re here, we’re at the airport. I’m tied up till 4 o’clock, he said, but please come by then and he gave me the directions.

John lived [00:14:00] on a spectacular estate just out of London. I believe it was about 90 acres in total. All kinds of ponds with swans in them. And just an incredible, incredible place. He welcomed us as a real gentleman. We had a lovely chat. He said, would you like to see some of my toys? Of course. And he took me over to one of the buildings beside his home that had, I don’t know, about a dozen varieties of Ferrari.

And I was just drooling all over every one of them. And then he said, oh, let’s go to the next building, open the door, and here’s all his world championship motorcycles. I was absolutely blown away that this man, this god in racing, would welcome me so openly and treat me so beautifully. We went back to the house, and he explained that the oldest part of the house was from the 13th century, and the newer wing was from the 15th century.

He would love [00:15:00] to have us stay overnight, but the guest suite is being renovated. But please come back when you’re through your touring outside of London. Before you go to London, we’ll invite you for dinner. I thanked him profusely. I said, absolutely, we would do that. And he said, by the way, I’ve arranged, since I couldn’t put you folks up here tonight, there’s an inn down the road, the Henry VIII Inn, a bed and breakfast.

We got there, the place was amazing. Again, I thanked him profusely. We were ushered into the Anne Boleyn room, one of the eight wives, I guess. Everything was wall to wall red velvet. It was mind blowing. Went down for breakfast the next morning, had a lovely English breakfast. And we were ready to check out.

I went down to the front desk. I said, I’d like to settle my bill. Oh, that’s quite alright, Mr. Birnbaum. Mr. Sirtis has taken care of this. My jaw dropped to the floor. I just couldn’t believe his hospitality. I don’t claim or pretend to be a [00:16:00] media star, but this was just overwhelming. We went and did our thing for the next 10 days, came back, called up John.

I said, we’re through touring and if you’d like we could come by. You suggested the possibility of dinner. He says, yes, we have it all arranged. Please come by. His formal dining room must have been 50 to 75 feet long without exaggeration. Longer, almost as long as the entire auditorium. And the table was the full length.

He had set one place for himself and his new wife, Jane, who happened to be the nurse that nursed him through his recovery of the accident at Mosport. He was set up at the far end of the table and had Melanie and I set up at this end of the table. We all had a great laugh out of that. And then he moved the two play settings down and we had a wonderful dinner.

Wonderful chat back and forth. I was just overwhelmed. And this is the kind of driver and superstar in motorsport [00:17:00] that I don’t think exists today. These were truly the golden years. He was amazing. As a professional accountant, I am acutely aware that at the end of the day, dollars and the economics greatly impact each and every endeavor, and eventually drive the direction of its development, no matter what it is.

This fundamental concept was certainly true in our beloved sport a half century ago, and still today. Notwithstanding all the enthusiasm for Mosport and Mont Tremblant, as the years unfolded, it became apparent that neither of those tracks were financially viable, nor could they meet the rapidly escalating costs of a Grand Prix weekend.

Fortunately for us all, the municipal, provincial, and federal politicians, Montreal, the province of Quebec, and the federal people in Canada, miraculously agreed on one thing and the Canadian Grand Prix found a permanent home in Montreal in [00:18:00] 1978. It is still held there today and will be into the foreseeable future.

It has been reported that well over a hundred thousand spectators pay to see the race on race day in Montreal and the week long activities that go on and the parties and all the closed streets events in downtown Montreal Generate some 90 million dollars for the city’s economy. Numbers that neither Mosport nor Mont Tremblant could ever match.

So I’m getting into some of the drivers in Canada, the manufacturers, the teams. A gentleman in Montreal called Peter Broker, who sold and manufactured performance exhaust systems for sports cars and sedans in the late 50s, early 60s, called the Stebro exhaust system. And he built a Formula Junior called the Stebro Formula Junior.

In those days, the Formula Junior specs [00:19:00] were very close to the F1 of that season. And he did whatever mods he had to do, entered it here at Watkins Glen, was accepted. So really, this is the first Canadian built Formula One car that ever raced. The next gentleman is Peter Ryan. His father had a hotel, a ski resort, in the Mont Tremblant area way before the track was built.

His father was from Philadelphia, Joe Ryan, an American. Peter was born in the States, but grew up in the Mont Tremblant area. He was a downhill ski champion. And was incredibly fast, won many Canadian championships. And the year that the Olympics came up, there was a great controversy as to whether he could enter the Olympics as a Canadian or an American.

Eventually he didn’t race in the Olympics and he turned to cars, fortunately for us. So Peter, in the early [00:20:00] 60s, he had a Porsche 550 RS as his first toy that he drove around the twisties in Mont Tremblant. And the skiing helped him to feel whatever was under him that was on the edge of adhesion. and developed his control and his talent of the car enormously from that skiing exercise.

He had the Porsche RS, then he got an RS60. He had a tremendous dice with Roger Penske at Lime Rock. Roger then had a Birdcage Maserati, and they had a tremendous dice the entire race. Roger won it, Peter was second. Roger invited Peter into the car for the flag victory lap. The sportsmanship was fantastic in those days.

Peter then got a Lotus 19, came to Mosport before there was a Formula One, but they called it the Canadian Grand Prix. Sterling Moss was there in a similar Lotus 19. I believe the first year they called it a [00:21:00] Lotus Monte Carlo. Pedro Rodriguez had a three liter Ferrari, a V12, and there was a number of other international stars.

Peter won the race, beating Moss, put on an enormous show. His talent was fantastic. Colin Chapman heard about it, and signed him up to have a season in Europe in the Formula Junior Lotus Series. That was just the developing stages for Formula One. Things went awry, and long story short, in one of the races at Reims in France, Peter was killed in that car.

He would have been one of the first Canadian superstars, without a doubt, but we lost him before we had a chance. The other people that have competed or been in Formula One, Bill Brack in the high back wing car, I believe it was the Lotus, competed three times in the Canadian Grand Prix, and they were all rent a rides.

Epi Weets was a rent a ride in one of the years, and under the [00:22:00] auspices of Team Canada. Al Pease, that George mentioned, had a ride in Formula One, and didn’t show too well. George Eaton, he bought a ride with BRM, and he didn’t show too much in his various years. Phil Villeneuve’s brother, Jacques, not his son, and he tried on, I think it was two occasions, in the Arrows, to qualify for the F1 in Montreal, and he just wasn’t fast enough.

But he did try. The last race at Mosport in 1977, and George mentioned this, Jody Schechter won it in the Wolf. Walter Wolf, who was originally from Austria, made a fortune with oil drilling equipment before he moved to Montreal, became a car enthusiast that went on to building his own car. He bought up 60 percent of the Williams team [00:23:00] that year, and the team that James Hunt was involved with was going out of business, so he bought up the assets of that, and that became the basis of the Wolf team.

Here we are in Montreal, Jill in the Ferrari and the wolf behind, and I believe that’s Kiki Rosberg, whose son, Nico, won the World Championship last year. Jill Villeneuve in his younger days, very personable, very down to earth individual. He started his career on snowmobiles and snowmobile racing. And like Peter Ryan, he felt the edge of adhesion and control.

On ice and snow, and that brought him into four wheels. He started with a Formula Ford, and he immediately began winning races. Moved up to Formula Atlantic. He was fearless. Nobody would push him off the track. Nobody would gain an inch on him if he could avoid it. And he went on to bigger and better things and [00:24:00] eventually Formula One.

Jody and Joe were teammates for Ferrari. They were the best of friends. Jody referred to him at his funeral in the eulogy as one of the fastest racing driver in the history of motorsport. He was absolutely adored in Quebec. He grew up in Montreal, or just east of Montreal, in Bircherville. The next year in Montreal, Alan Jones won the race, and they had a fantastic race.

There was no trying to push anybody off the track. Good, clean racing, wheel to wheel racing. Alan won it, and he wanted to hold Jill’s hand up to say he deserves a lot of the applause as well. Great friendship, great sportsmanship. Gilles never gave up, never quit. He would just keep going, he’d beat the hell out of a car, he’d extract the absolute best you could ever get out of a car, and this is what made him such an amazing driver.

And young Jacques, his son, that later got [00:25:00] into Formula One and actually won the World Championship. Of the 40, 000 images I have in my historic collection, this, without a doubt, is my absolute favorite. Gilles winning, his hands up, the flag, the banner. The crowd behind and I must admit that I had a bit of a, an input into how the picture was put together.

I went to the flag marshal about five or ten laps from the end and it looked like Joe was pretty certainly going to win it. I said, look, don’t start waving the flag when he’s a half mile down the track. I want you to time it so that you just about hit him over the head with the checkered flag as he crosses the finish line.

I went down about a couple of hundred feet from the finish line, got right up at the guardrail, pushed people out of the way, I didn’t give a damn. I was gonna get this picture. It’s my absolute favorite, it’s been on magazine covers, it’s in my book. It just tells the whole story. And now we’ll go to just some wrap up [00:26:00] pictures.

A very early portrait of Jim Clark. Phenomenal racer. You could see the difference in the helmets, the face goggles. The so called driving suit. I don’t even know if it was fireproof in those days. This is about 1960 or 61. Here is Bruce McLaren in one of his early races. This is an overhead of Jackie Stewart in the BRM.

And this was technically called an H 16, I believe was the designation. A 16 cylinder motor. This was a race at Mont Tremblant, one of the double winged, split in the middle and flexible, and that’s the smaller front wing. And this was the only split wing in the rear, I believe. The strut went right down to the suspension member on both sides, whereas the other ones would go straight to the frame.

And what that did, as the rear suspension on one side moved, half of the rear wing could move in the same [00:27:00] direction. The double wing cars and the high wings were gone the next year, but for the techies, I guess they love that kind of picture. Jackie Stewart in his earlier days, in his famous cap. Jackie Ickx winning the event at Mont Tremblant.

Denny Youn. This was the start of one of the races at Mosport. I forgot to mention that with Jill. I happen to be up in the press room. and was watching as they came around this almost 90 degree turn onto the pit straight. Joe was in a Formula Atlantic pre F1 days, and he lost it. And as Sterling Moss said, you don’t know if you’re going fast enough until you lose control of the car, and then you’d know you’ve gone over the line.

Joe would test that just about every race, every day. He lost it coming around onto the pit straight. This was not a wall at that time. It was just a barrier dividing the track from what was the pit just behind it. And I looked down at the track, and Joe [00:28:00] came around, did a complete 360, and was backing into the barrier, dividing the track from the pits.

And I was looking down at him, and I saw his hand grab the shift leader. Before he stopped rolling backwards, he had it in first gear, he glanced down the track to see if anybody was coming, let the clutch out, and went screaming down the track. I don’t think that entire episode lasted two to three seconds, but it’s been burned in my memory ever since.

What he could have done, and the timing, was just phenomenal. Colin Chapman on the left, and Ken Tyrell chatting in the pits very casually. Two superstars, very well known people. Roger Penske and Mark Donnie. What an amazing pair that just had the most incredible marriage in terms of the driver, the car, the team owner, and what they could do together.

Then we have the first and only six wheel car ever to race, the Tyrrell. I believe that was [00:29:00] Patrick Depay at Mosport. He’s just coming into the pit lane. James Hunt, I was experimenting with some very tight close up shots as they whizzed by, and panning with the camera, even with the good speeds of the lens in those days.

Sometimes I was on with the focus, and sometimes I wasn’t, more often than not. But this time I was on and it’s a beautiful picture. Nicky Lauda in the Ferrari. Alan Jones in the Williams. But that’s one of the enormous sculptures that was on the site in Montreal at Expo 67. And was there for a long time.

I’m not sure if it’s still there or not. 79 in Montreal. Alan Jones won the race. And went on the victory lap with the flag. This is a picture I enjoy, not because he wrecked the car, but Rene Arnoux and the Renault Elf stuffed it into the guardrail, got out and started walking away, and I just caught that expression on his face.

Oh my goodness, what have [00:30:00] I done? My French is lousy. Unfortunately, this picture doesn’t show everything, except the drag strip that’s going down pit lane at Mont Tremblant, and it says, Happy Motoring. And that is my presentation. Thank you. Applause

And now, I’ll introduce Tim, and it’s his turn. Okay, turning to Tim. Tim was a pit and paddock marshal as well as a flagger for four years of mass sport. He then worked as a flagger at every station in Montreal until his last race in 2012. Overall, he has worked at 65 Formula One races in Canada or the United States, including the first United States Grand Prix at Austin in 2012.

Since I came back from Germany in 1967, I’ve flagged for the first Canadian Grand Prix. I went up intentionally just as a spectator because I’d only got back into the United States the [00:31:00] Friday before. So, I missed the U. S. Grand Prix that year because I was mustering out at Fort Dix. I got up to Canada and bumped into the paddock marshals.

The one in charge knew me from Europe and invited me to be a paddock marshal for the weekend. Sure, why not? At that time, they were called Perry’s Merry Men, and I got to look after the Ferrari team for the weekend. Good start. Didn’t know anything about that part of racing. At that time, I was… I’d driven race go karts when I was a kid, and did a lot of high speed stuff in Germany.

But I had the opportunity to get involved. The following year, they’d gone to St. Gervais, did Perry’s Merry Men for that one again. But in the meantime, I’d become a flagger in the U. S. I did two years as a paddock marshal, and then I flagged all the rest of the races at Mosport. I actually [00:32:00] flagged every station at Mosport, too, in different categories.

In F1, I worked Station 2, the day the Ernie Strong and James Hunt thing happened. And Station 2 3 is where it happened. James Hunt was upset because he had been punted off. He didn’t go off on his own, he was helped. And James wanted to punch out the helper. And that’s when Ernie Strong tried to grab him and prevent him from doing that.

James just came around and knocked Ernie down and I kind of just chuckled. I said, Ernie, you weren’t paying attention. Ha, ha, ha. That turn is a blind, hellish turn. You go through two and drop down. You go into no man’s land. And in six hour racing up there, there had been a few fatal accidents where somebody went over the hump, went all the way out to the guardrail, [00:33:00] which was almost 150 yards away, and still got killed.

I’ve been involved in an awful lot of that type of thing in my years. In the early era of racing that we’re talking about the most part, we were losing two drivers and two flaggers every year. And that was basically all of the late, late 60s, early 70s, all the way through almost to the end of the 70s.

That ratio was keeping up throughout the world, you know, I mean, it was a dangerous game. But I still loved it. Maybe I’m not all here, but taking risks, doing that type of danger, is the only reason I wanted to work Formula 1. And it’s the only reason I’ve done 65 Formula 1 Grands Prix as a flagger. Two is a paddock marshal.

One is an intelligent observer. Somebody that’s helping corporate. That wasn’t in Canada. After [00:34:00] Mosport, we went to Montreal. I don’t remember when these bibs started, but I have 10, 11, 12, and I know I’ve got a lot more, but they’re not stored in any particular order. All the ones I brought, these are Canadian.

The reason we got these, those numbers, the TV camera can pick them up. Very easily. So if you do something bad, you’re never coming back. And you might even be fined or kicked out of Canada. We had one flagger that picked up a piece of a car at an accident scene. Wasn’t a valuable piece. Wasn’t worth anything.

But he was asked to leave Canada and never come back. Heh heh heh. These bibs serve a purpose. And it’s not what you’d think. You know, Sitting here, I realized, Even though this is an aerated fabric, it looks, They’re hot! Now that I think about it, I remember that from wearing them. No matter how good your, uh, Flag [00:35:00] suit was, and, Of course I flagged with full Nomex, That’s hot.