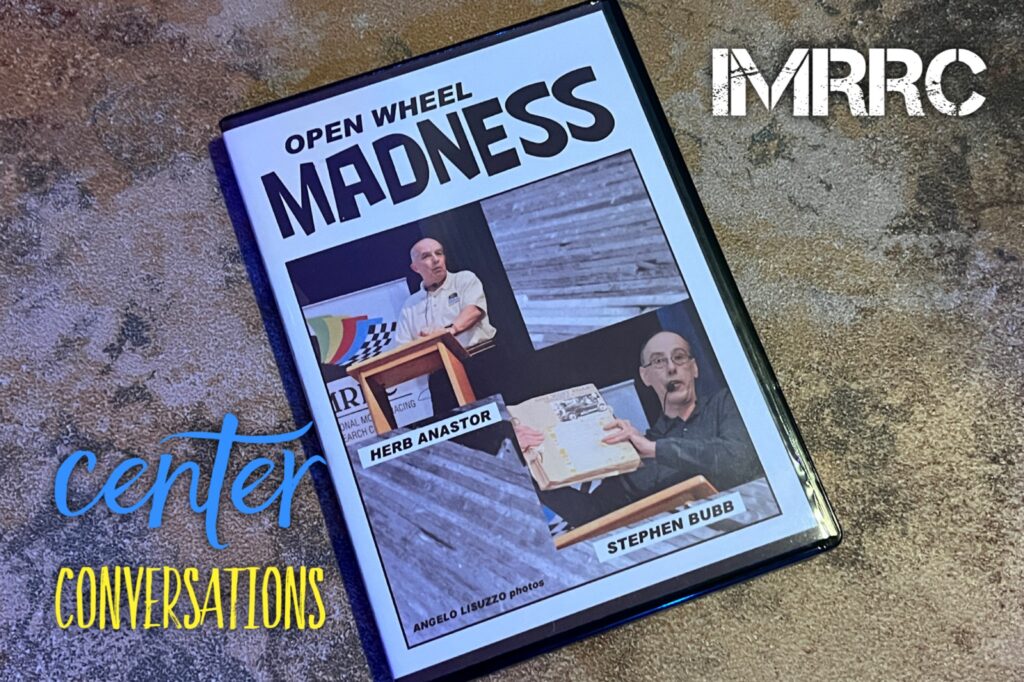

As we prepare for the 108th running of the Indianapolis 500 this memorial day weekend, let’s step back in time and learn about how it all got started. We present you with a 2-part digital remastering (and original videos) of “Open Wheel Madness” presented by automotive historians Herb Anastor (SAH) and Stephen Bubb (EMMR).

Part-1: Herb Anastor

Check out the full-length video version of this presentation!

Part-2: Stephen Bubb

Check out the video version for Part 2 of this presentation.

Credits

This episode is part of our HISTORY OF MOTORSPORTS SERIES and is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Transcript (Part-1): Herb Anastor

[00:00:00] BreakFix’s History of Motorsports series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argettsinger family. Well, my name is Kip Sider. For those who may not know, I’m the Visitor Services Outreach Coordinator for the International Motor Racing Research Center.

And I want to welcome you all here. Thank you for taking a little time out of your afternoon to come visit us as we talk about open wheel madness. Before we get going, I have several people I need to thank on this. First of all, and foremost of all, are our two speakers, Mr. Herb Anistore and Stephen Bubb.

When we were considering putting this program together, I emailed Lenny Sammons from Area Auto Racing News and asked him what we were projecting to do and who might I get that would be experts in their field. And Mr. Sammons immediately suggested Herb and Steve. We are very happy and very honored to have them here today.

I am personally fascinated at both of the things they’re going to talk about. Herb is talking [00:01:00] about board track racing, which I have been fascinated about for a number of years. And Steven’s going to talk about sprint car and open wheel racing in the twenties and thirties and some guy named Al Capone and what he had to do with racing.

And that was the hook that got me psyched on his talk as well. So I certainly want to thank both Herb and Steven for coming here. Herb, I’m going to invite you up now, so settle back and relax, and Herb, come on up. Kip, thank you, uh, gee, a nice crowd, and it’s an honor to be here because I know the people who’ve been before me and the people who are involved in this organization, and it’s something I never really would have ever expected, so thank you all for coming.

I hope we have some fun this afternoon. This is something that I’m interested in. Kip has asked me to talk a little bit about myself. We live in Vineland, New Jersey. I was a school teacher for 25 years, taught health and physical education, and for much of that time while I was doing that, I was also working at the local newspaper in Vineland.

I was a sports writer, and the last two years I was a daily [00:02:00] columnist, which means I went into the office every night and I sat and looked at that screen for two or three hours before I wrote anything, which had to be printed the next day, so that, that was always a lot of fun. As far as automobile racing goes, I got involved as a kid going to the Vineland Speedway, which was in our community.

It started out as a dirt track, then it became asphalt track. My family wasn’t really racing fans. Before I was old enough to drive, my dad would take me to the races because he knew I liked the racing. Then when I got old enough to drive, I was a drag racer, became an official at the track, was a starter with flags.

I’m that old. Our track closed. My racing got involved with more with what you could see on TV, reading National Speed Sport news, articles like that. I got involved with Lenny. I’ve been writing for about 40 years, area auto racing news. I was also a contributing editor for 20 years with stock car racing.

I worked for Jimmy Horton when he was doing his modified racing. He still is. I was 11 years. I worked on [00:03:00] that crew did tires crew set up car involvement and things like that. I’m really interested in the history of automobile racing. It’s just so interesting to find out how we got to where we are. Board track racing is part of that.

Before I go into what I’m going to speak about today, which is really more of an overview, because there’s so much you can talk about in all this, I want to point out this painting. This was done by Joe Henning, and he’s a motorsports illustrator, and the man in the white car is Frank Lockhart, and that’s a rear wheel drive Miller, and the front wheel drive Miller is Peter DiPaolo.

When I asked the people who had this painting if I could use it, they had no question about it. They thought this would be a terrific idea, and that’s why I left the logo, which you can see, is the American Hot Rod Foundation. American Hot Rod Foundation is an organization much like this. They deal with old time auto racing.

And the history of the sport, board tracks a little bit, mostly with hot rodding. It’s not a bad [00:04:00] idea if you’re interested one time and you’re sitting at your computer to just type in American Hot Rod Foundation and see what they have to offer. I think you’re here today because you enjoy this kind of thing.

And that’s a nice activity to get involved. Velodrome is a French term meaning bicycle racetrack. And this is what became very popular in Europe. People racing bicycles on these oval board tracks eventually came over to this country, and there were velodromes throughout. Bicycle racing was very popular at the end of the 1890s and early 1900s.

Many of the early automobile racers were bicycle racers. The Wright brothers were bicycle racers. So if we’re going to race bicycles on a wooden track, well, motorcycles aren’t that much bigger. So let’s try them and they did that too. Those people really did things that were just unimaginable.

Motorcycles and velodromes were raced with the throttle wired full force. So they’re going around full force with no brakes. A lot of [00:05:00] accidents, a lot of people were killed, but this is what they did and people continued to do that. Someone thought, well, if we have bicycles and motorcycles, maybe we could have automobiles on a wooden track.

The first track that was ever built. For automobile racing with a wooden base was the Playa del Rey in Venice, California. It was a one mile track 1910 and it was in Los Angeles and it was designed by Fred Moskowitz and built by Jack Prince. Jack Prince was a bicycle champion, came to this country to build these race tracks for motorcycles and bicycles and Moskowitz and Prince put this track together.

This was a one mile track banked 30 degrees. Moskowitz was really excited about this, but Howard Marmon, who had the Marmon Automobile Company, said, You know, this is okay, but these guys aren’t going to do that good. And Moskowitz said, 5, 000 bet that they would go over 100 miles an hour. Now 5, 000, as we [00:06:00] see, is about 133, 000 today, so this wasn’t a small wager.

And he lost that bet by less than one mile an hour. The car that went the fastest at that time was Barney Oldfield, but this was the first track. There were 24 of them from 1910 through 1931. The second track was built in Oakland. This was where Jack Prince’s headquarters was, and it was in 1911. It was a half mile track.

You can see there were also three other half mile tracks that were built late in the 1920s. These tracks were wonderful board tracks for the racers, but they never had a triple A national championship race. That was always on a track that was a mile or longer. These four other tracks in Oakland, Akron, Bridgeport, and Woodbridge were more like a local weekly track.

They had regular races, sometimes they had special events. Sometimes they were run monthly, depending on the popularity [00:07:00] of the races. They were more of a local flavor, other than the rest of the tracks which we’ll see, which were all National Championship tracks. You see, from 1910, it took until 1915 for the next track to be built.

That was in Chicago, was a two mile track. Tacoma was a two mile track and Omaha, then Des Moines. So you had four tracks within one year that developed into something that became a national championship circuit. All of these tracks were run for a variety of years with a variety of winners. And the history of all these tracks, we could spend hours on.

But we want to talk a little bit more about the overall nature of board track racing. And in doing that, here is what the coverage was in the newspapers of the first board track races. Now, Playa Del Rey, This was a week long activity. It had a wide variety of things that took place. Notice the headlines.

They were running this [00:08:00] mile track in about 37, 38 seconds. But notice the cars that were being raced. These cars were basically the cars that were by the manufacturers, and they were just stripped down. They had wooden wheels. Tires sometimes were solid tires. They weren’t all necessarily rubber tires. But look at the coverage that was given.

To what was taking place. Here’s the Marmon Pier in the top corner. That was driven by Ray Haroon. You can see the other vehicles in there. How heavy they are. Imagine going 90, 95 miles an hour in something like that. And this is what these folks were doing. Notice the Michelin tire ad. Michelin was a great supporter of automobile racing.

In fact, it was one of the leading automobile racing tires at the time. The Fiat ad on the side here. talking about Ralph De Palma and Caleb Bragg. They were two of the drivers that were Fiat racers and what they talked about when the Fiat and the power of the race car, and then the records that were being set [00:09:00] this first week of racing board track in California had a variety of things.

There were races of maybe five laps going on. There were challenge races. They had a wide variety of engine sizes, so that someone would race. We’re going to try and set a record for a 100 cubic inch engine. We’re going to try an engine that’s 300 cubic inches. Things like that. And this went on for that week.

1910, the Playa del Rey. Notice the people standing outside the track. Notice that the track wall is perpendicular to the ground. Not perpendicular to the racetrack. In the early tracks, this caused a lot of problems. Cars would go into that and just go over the top. They wouldn’t necessarily come back in.

But you see how these cars were? There were two man cars. There were one man cars. Notice the gas tanks. Just regular gas tank that was in the automobile before they stripped the body panels away. Here is more coverage. This is Ray Haroon [00:10:00] driving his Marmin. He won a 100 mile race. Hello Los Angeles Herald, this was a front page story.

This was April 10th, it was in early April when the track opened. In June 1910, here was an article by the New York Times comparing the board track in California with the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, which had only been open since 1909. How the comparison of the two, what could be done to the automobile industry, because automobile racing at that time was really a development.

of the automobile industry. This is how people tested their cars. There was no test track. They were racing on fairgrounds. They were racing point to point from city to city, or a city would lay out a course and they would race around that. And there was questions about the board tracks getting bigger and more popular and things like that.

New York Times at the time was the newspaper of record. Here’s another photograph, Beverly Hills racetrack. This was 1920 to [00:11:00] 1924. Notice what it looked like when it was in operation. That’s Santa Monica Boulevard and Wilshire Boulevard. Where the big red dot is is the approximate location of the racetrack.

The racetrack actually came back beyond where the red roofed houses are. You can see the size of this. This was a two mile track. This was in 1920, and this was the first track that used Searle’s Spiral. Easement curve. This actually was used by railroads to make it easier for trains to go around the curve.

Let’s say you had a curve on your track. First turn was 1, 500 feet around. Let’s just use that for numbers. Easement curve would, every 500 feet, it would shorten for a little bit the radius on that curve, so it would be easier to turn the car through the turn. Then when you got through it, it would go the other way.

And Art Pillsbury used this with Jack [00:12:00] Prince. This is when they first became partners. Pillsbury believed this was his way for the cars to go around these tracks at the high speeds that they were going. And he also said an ideal board racing track would allow a car to go around without turning the wheel at all.

When we drive on the highway, you’re going around the curve. You’re going to turn the wheel a little bit, little bit this way. You would just hold your hand steady and the car would go around. What made it so possible for these cars to go very, very fast for their time. Imagine now how many people realize that where they once lived was a racetrack.

I don’t think many people would 2019 picture of Santa Monica and Wilshire Boulevard. Board tracks were easy to construct because it was framing a house, effectively. You had long, 18, 20 foot, sometimes longer, pieces of wood that were put down on a frame. And in other photographs, you’ll see the [00:13:00] outside of how it looked.

And you just needed a lot of men with a lot of nails and a lot of hammers. The Atlantic City Motor Speedway was a mile and a half. They built it start to finish with 700 men, and all they did was just pound nails. The tracks approximately on the straightaway were from 40 to 60 feet wide. Turns were 70, 75 feet wide.

They used millions of board feet. They used whatever they could to bring the product into the area where it was being built. From heavy trucks to horse drawn wagons, because remember, this was the early part of the 20th century. You see the steep nature of the board track. This is a turn, and it looks much like someone when they’re going up the roof of a house sometimes.

It’s really pretty effective. They went up rather quickly when they were built. The only problem with wood out in the weather is unless you do something to preserve it, you’re going to have some problems, and there were no tracts effectively that used any kind of wood preservative. Most of the [00:14:00] wood was pine wood like you’d use in a house construction.

Some tried harder woods, but that didn’t necessarily work either. And you can see the damage to this board track. What would happen during the races when something broke, which did, it would sit from underneath. Peter Palo one time said the most interesting thing he experienced as a board track racer was the head of someone popping up in the hole to see where he had to fix the track.

This is a picture of the Laurel Speedway, which was also known as the Baltimore Washington Speedway. This is opening day, July 11th, 1925. You can see in the far corner the, uh, banking and how that looks, and the massive size on acres of ground these tracks were. But the thing that impressed me most about this picture, and look at all the straw hats, there were not very many women that were in the grandstand and wherever area this was taken.

This was one of the more popular tracks, and as I pointed out here, you went to the races to see [00:15:00] things, but you also saw things besides racing cars. Frequently airplane demonstrations, because in the early and the late teens, it was a new item. They had balloon races, daytime fireworks, bands that were there.

My uncle and my grandmother and grandfather went to the track in the Atlantic City Motor Speedway. And my dad said that he remembered all the people that were there. There were 85, 000 or so at the time he went, and all the cars. And they had an interesting race besides the automobile race. They had what they called an ambulance race.

They had half a dozen race car drivers, a half a dozen ambulances. A half a dozen doctors and a half a dozen orderlies. And on the backstretch of the Atlantic City Motor Speedway, they had six dummies that were supposed to be injured people or someone who were needed medical care. And the idea of the race was to see who could get to the dummy first and get back to the starting line and that was going to be the [00:16:00] winner.

They also had stock car races at these and we’ll talk about this later. My father said, because he became a doctor, that was something he remembered from the race, other than all the excitement of that. But this is just a general good look at an opening day at a board track speedway. Notice all the people in the infield.

Notice all the people in the grandstand. Ticket prices were a dollar. Up to 10, 12, which again, we’re talking about times in the 20s and so you could say a dollar in the 20s is worth about 15 today. So it was a good chunk of your money, but the people had a good time and the board tracks attracted a lot of attention.

Here again is the board track in at Baltimore, Washington. Notice the extreme banking of the speedway, the cars, millers down on the lower picture going into the first turn. Fields of races had anywhere 15, maybe 20 were the top number in the entry. But you can see on the outside [00:17:00] of this lower picture what some of the support structure was.

All wood. There were two tracks that didn’t have a wood base. The Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn. That was a metal base, and the other was the Tacoma track, which was actually built in the ground. This was a mile and a quarter track, and because of the nature of board track racing, speed was the thing that was involved, pit stops, and so those weren’t really expected.

If you had a pit stop, you were not going to race for first place. This was a 45 degree banking in this track, and that’s generally what the banking was in these bigger tracks. Here is the Tacoma track, and what’s interesting about this track, as I said, is this track was built in the ground. You can see in the picture on the right here, they built the banking.

You can see the dirt. They put the boards in the ground. And then they filled it with asphalt. Notice the two race cars on the bottom here. You can barely pick it out, but they have a screen in front of their radiator because the asphalt and gravel didn’t do [00:18:00] anything but come up and bang into the cars.

In fact, there were frequent tire explosions. The drivers were injured. Notice they’re two man cars. Tacoma, to compensate for this, placed high winning prizes so they would get all the top drivers. But of all the tracks that were national championship tracks, this was the one that was most disliked by the racers.

In fact, one of the comments was at the time, board track racing is really not that much fun because the tracks are not good. And then there’s Tacoma. The other thing that’s interesting about the Tacoma track is, notice that it’s not a round track or it’s not an oval track. It was built on the land that was available, much like the Darlington Speedway has the two different curves.

But the other thing that’s interesting about this track, it’s one of the very few that is even recognized today as having been there. There’s a historical marker in the center of the track. picture that shows where the Tacoma track was. What is located [00:19:00] where Tacoma is now is a community college. These are the people who I would say are probably the most famous people to come out of the board track era.

Jack Prince over on the left. You can see he was a big, strong man. Most of the big, rugged guys, because the race on big bicycles, they weren’t the three pound machines that are available now. Jack Prince was from 1910 to 1927 involved in just about all the tracks. Although when Art Pillsbury joined him in 1920, the whole nature of the board track development changed just because of that spiral easement curve.

The interesting thing also about Art, after he designed all these board tracks, he also became a top ranked official in the American Automobile Association’s, uh, racing situation. He was the West Coast supervisor for a long time, and he had important roles at the Indianapolis 500. The bottom four people are four men who did a lot for [00:20:00] board track racing, especially in the second part in the 20s, because most of the cars were Miller’s or Duesenberg’s.

Harry Miller, of course, was a famous person before he even got involved in racing because he manufactured carburetors. Here’s an ad for a Miller carburetor. Dario Resta, Johnny Aiton, and Eddie Rickenbacker all used the Miller Carburetor, and that was a popular carburetor used by lots of people in lots of different things, not only in automobile racing, but in make your car better.

One of the things that was interesting, the research of this era, there were a lot of aftermarket companies that were making things to make the automobile that the people were driving daily a better automobile. Lower picture shows Harry Miller with one of his Miller engines. They were straight A. He was involved with the Puget Grand Prix car before he got involved in racing on a full time scale.

The maintenance of that car and the Puget had a lot to do [00:21:00] with the development of the Miller engines and also the Offenhauser engine, which you see on the right here. Interesting thing about Harry Miller is his shop foreman was Fred H. Offenhauser, who became the man who developed the Offenhauser racing engine.

It’s also another Fred Offenhauser, Fred C. Fred C. was Fred H. ‘s nephew. And they worked together, but they didn’t like each other very much. They had problems working together, but they did. And Fred C. was a pretty decent machinist, so Fred H. caped him around. Fred C. went in the Navy and World War II. And after he got out of the Navy, he saw it.

Well, I don’t want to work for my uncle again. I’m going to start my own business. He’s the man that developed the Offenhauser speed equipment. The stuff you see, the valve covers, the intake manifolds, this, that, and the other. They had problems with the name. One thought the other shouldn’t be using the name.

So each one sued the other. Took this to court, and they sued because [00:22:00] they wanted the exclusive right to use the name Offenhauser. Well, the judge, I guess this must have been a fun time too, having two people yell about the same thing. The judge decided they could both use the name Offenhauser because it was their name.

However, legally, the judge ruled that the only thing that could be called an offie Is the four cylinder racing engine. So if you hear I got off the head covers, actually they’re often Hauser ed covers. They can’t use the name. The other thing about the, uh, off the engine is that Leo Goosen from the time he began working with Harry Miller right up until his death, and he passed away in 1974.

He did a great deal with automobile racing engines. He was the one when George Sally decided he wanted to have the lay down engine in his 1957 Indianapolis car. He’s the one that redesigned that so the oil would flow properly because it was 18 degrees from being [00:23:00] flat. An outstanding gentleman and Harry Miller thought enough of Leo Goosen to tell him In 1925, you’ve done outstanding work for my company.

I appreciate everything you do. This year, I’m going to pay you a dollar an hour. That was a high, high rate for him. And at that time, that was about 15 an hour in today’s money. So those are people, and of course, the Duesenbergs are interesting. Because they were in automobile racing, actually, to sell automobiles.

They made their racing cars because the Duesenbergs were sold to people only as rolling chassis. If you wanted a Duesenberg, you would buy the Duesenberg rolling chassis, then take it to a body man, and he would make it. for you. Here’s a example at the top left of Eddie Hearn, who was a Duesenberg racer.

And if you can see the ad, it tells about the engine, how powerful it is because they’re selling the engine. They’re [00:24:00] selling. The Duesenberg Model J, the lower part, talks about the frame and the engine. And you would buy Duesenbergs for 8, 500, then take it to a coach builder who would complete your car. In the time that the Model J Duesenberg was being sold.

8, 500 was about 125, 000 in today’s money. That’s just for the chassis, tires, wheels, running gear. Then you take it to the coach builder and he would charge you at least that much or even more. It’s possible that these cars together were worth a quarter of a million dollars in. The late 1920s. There you see Duesenberg Model A chassis.

That’s what the ads were all talking about. The top picture there is of Peter DiPaolo’s 1925 Indianapolis 500 winner. That was a Duesenberg and the difference between Duesenberg Racing and Duesenberg Motors is all the [00:25:00] Duesenberg engines were fashioned by the Lycoming machine and they were designed by the Duesenbergs.

But they didn’t have an engine manufacturing situation like Miller did. I mentioned E. L. Cord in the back, in the end of that sentence there. E. L. Cord bought the Duesenberg company in the late 1920s. And he developed the Duesenberg as part of the, uh, companies that he owned. And there’s that straight eight Duesenberg logo, which was very famous at the time.

This is maybe the most interesting car that ever raced on a board track. See, Hal Scott Aviation Motors. This was a man who developed aviation engines in race cars, not in airplanes. And you see, it looks really like a giant go kart. And he raced it at least one time, I’ve been able to find, in April 1912, on the half mile Oakland track.

So it was just an unusual thing, but it was also a very fast car. It was one of the first to ever go 60 miles an hour, which at the time was really going [00:26:00] something. Just the kind of things during the early years of board track racing that you would see. These next few pictures are just to give you an idea of some of the cars that are raced.

Caleb Bragg is the man who beat Barney Ofield in that first race at Playa del Rey. But he was considered a novice driver because he wasn’t professional in his racing, he was a novice. And he actually took the place of Ralph De Palma, who was supposed to race against Oldfield. But there was something wrong with De Palma’s Fiat, so he substituted and he beat the famous Barney Oldfield.

Barney, of course, was a bicycle racer before he became an automobile racer. Also notice that these were both chain drive automobiles. And that Blitzen Benz, that was the world speed record holder at the time. Now we’re going a little later. This is 1916, a DeLage from France. There’s a Hudson. These, again, were cars that were stripped down, racing bodies put on, and they [00:27:00] used them as race cars and used them to test the vehicles that were being built by Hudson and DeLage.

Here’s a Stutz Bearcat and an early Duesenberg. Imagine, I’d say, going 100 miles an hour and something like that. With no safety belts. Nothing safety wise at all except what was built into the race car. Another thing that was interesting doing research on board track racing was the artwork and how the things were designed, the race programs.

And so this is a 1915 souvenir program at Sheepshead Bay. Just a beautiful painting. Look at some of the cars in the pictures below. These were standard automobiles that had been converted. They were all two man cars with a variety of engines. And again, note the guardrail perpendicular to the ground, not perpendicular to the race course.

Now we’re getting into some of the more famous names. This is Lewis Chevrolet. This is a red Buick Bug. We forget a lot about, uh, [00:28:00] people back then that there were colors for these cars. And this was a beautiful red car. Buick’s the oldest active name in the American automobile industry. And this is a car that Lewis Chevrolet raced on board tracks and so.

Just a pretty car. And it was something, again, you see, uh, very basic and a lot to handle. And in the bottom, you see the Frontenacs, which were the cars that the Chevrolets built. We talk about the Fronties and the Fronty Fords. We talk about them. In research, I found these Fronty cars were sometimes called Chevrolet cars, even though Chevrolet was no longer involved with General Motors.

But so famous, they were recognized as such, and there had board track victories in these. And again, these were two man cars that were done because that’s the way the AAA had their ruling for that time. High speeds, 115, 120 miles an hour as we see. 622 cubic inches. It’s a big engine to produce just 58 horsepower, isn’t [00:29:00] it?

This is the racing car that Harry Miller ever built, called the Golden Submarine. He and Barney Oldfield built it, as Bob Berman, who we mentioned before, was their great friend. And Bob had a Peugeot, and Bob was racing in the Corona race in California in 1916. When off the track, he was killed. His riding mechanic was killed.

Several other people were serious injuries because it was a road race and something happened to the car. And you’re standing a couple of feet away from the racing surface or the highway, because that’s, there just wasn’t any thought to anything. So they thought, how can we do something to protect the driver?

Harry Miller and Barney Oldfield put their heads together and they thought, well, if we build something that can enclose the driver and put. something over the top and that’s just what they did. As it points out here, this is the first racing car with a roll cage and it’s the first all electrically welded steel frame [00:30:00] automobile ever produced in this country.

This was a gold car, that’s why they called it the Golden Submarine. Harry Miller built a four cylinder engine. It was a two man car and you got in it and out the door. The exhaust pipe, however, From this design of the car went through the car between the driver and the passenger. Barney Oldfield raced this car quite a bit.

He did, however, flip into the infield lake at Lakewood Speedway in Atlanta, and that brought about picture number two. He almost drowned in that thing. So they cut everything away but the front of the bodywork, and he’s racing around in a vehicle that looks like that. With some success. And after he quit racing that car in 1908, the engine still ran very well.

And he liked the way that performed. He made this into the old field special Roscoe Sorrell’s riding mechanic, Waldo Stein. And this was the first car that was the Miller brand at the Indianapolis motor speedway. [00:31:00] This is Ralph De Palma, very famous, very popular. One thousands of races, supposedly. Steven’s going to talk a little bit more about Ralph De Palma.

How he could win a thousand races? Well, you figure races of one mile, one lap, because it was a challenge race. So you beat so and so, you won. That’s how that happened. But anyway, he was an excellent racer. And this is an automobile that’s built on the Packard chassis, but it was built by Packard because they were interested in airplane engines prior to World War I.

But they didn’t want to go through the expense of testing the airplane engine in an airplane. So they tested it in a racing car. They made a 299 or 300 cubic inch V 12 and they tested this engine for several years. And this is the engine that became the Liberty V 12 engine in World War II and it eventually powered the P 51, which was one of the outstanding airplanes of the Second World [00:32:00] War.

The other interesting thing about this particular car is we think, well, they didn’t have the Indianapolis 500 during the World War I and sometimes people say, well, there was no automobile racing during World War I. There actually was. There just was no national champion. There was no Indianapolis 500 because the 500 depended a lot on the European cars coming over.

So they raced quite a bit during the World War I years. But while they were doing that, Ralph DePalma was actually a captain in the United States Army, working on the development of this engine for airplane use. And Jesse Vincent was his manager at Packard. He was a colonel in this same unit, Wright Field in Ohio, working on the development of this engine during World War I.

Which became the World War II engine. There was racing and there was quite a lot of racing everywhere except Indianapolis. This is Lewis Chevrolet’s business. The [00:33:00] Frontenac Lewis and Arthur and Gaston Chevrolet were very famous automobile racers. This particular car is showing Gaston Chevrolet and it’s in his Monroe.

The Monroe race cars were green. The Frontenac race cars were the exact same race car, except they were red. So a Fronty and a Monroe were the same cars, just different colors. And Gaston Chevrolet was a very popular racer, very good racer. He was also posthumously Team 20 AAA champion because he was killed in an accident at Beverly Hills Speedway.

But you can see the board track, he’s there, see the wider panels on the infield and the racing 2x4s which were put on their end is what the race cars raced on. The front and ax cylinder heads were very popular on the Ford Model T and also you can see the advertisement talking about the fronty cylinder heads for other models.

Application Chevrolet, whippets, things [00:34:00] like that. These were again, part of the large number of people making aftermarket product. Match racing was popular during the early board track years. Here we have the golden submarine. We have the white, the palm of the car and the Chevrolet in the center. They toured.

As a group, and we did match races together. This particular race, there were three races. Ralph De Palma won all three. But look at all the people in the grandstands. This is Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn, New York. 1917. 40, 000 spectators at this board track event. This was the main attraction. All right, we talked about not having races during the World War I years at Indianapolis, but they did at Cincinnati.

This was, again, a two mile track, big track. Look at the grandstand, look at the lineup of cars. They ran five abreast, paid a lot of money. It was a thing that people were interested in doing even during the World War I time. Again, there’s a advertisement for the race. Look at the pretty colors, the artwork, look at the [00:35:00] admission price, dollar and a half.

Multiply that 10 or 15 times because the dollar was worth a lot more then than what it’s actual shows there. Here it says on the bottom about the Cincinnati track actually closed because of the exposure to the elements, but some of the wood was used to make a bar. That’s what happened a lot of these tracks too when they closed.

They couldn’t do anything anymore with the racetrack. But they would sell the wood to construction people and they would use the, uh, wood to build houses and whatever needed to be done. July 4th, 1919, celebrating Eddie Rickenbacker. Eddie Rickenbacker, some of you may know, was a very prominent automobile racer prior to his service in World War I.

And I’m just going to read here just a little bit about Rickenbacker to give you an idea, not only about Eddie, but the kind of success that people who were professional auto racers could have in these eras. Rickenbacker was from Columbus, Ohio. He was a young man whose father [00:36:00] died when he was 12, so he had to quit school and go out and work.

He got a lot of Part time jobs, a lot of jobs involving his hands. He became very interested in mechanical things and began taking correspondence courses in engineering. He would get a letter every so often and here’s this information he would do is send it back and get another one. And so. This is another way of education during this time when people couldn’t go to school, but they wanted to improve themselves in 1910.

He was 19 years old. He had been working at the Firestone Columbus factory in Columbus, Ohio, that made automobiles. They were made one of the first left hand automobiles in this country. He had been a riding mechanic in the Vanderbilt Cup races with Lee Frayer. He had been involved in this so much and had done so well that by 17 years old, he was the shop foreman of the machine shop for the Firestone Columbus company, but he wanted to do something better.

He wanted to improve himself and go on and do other [00:37:00] things. So they made him a salesman of Firestone Columbus cars, and he was given the Omaha territory. He was 19 years old at the time in 1910. And what this required was he would take people for rides and how good it was. And how powerful it was and how much this and that try and get them to buy it.

And then he’d encourage them to come out to the races and see how the engine performed against other cars. Cause they had lots of races on fairgrounds tracks and city to city, any place that had a race, he would compete in, in this Firestone Columbus car that he turned into a four cylinder racing car.

And he did very well as a salesman and he did very well as a racer. Raced at every race within a hundred miles of Columbus with one of these cars that he developed. 1911, he was a relief driver in the first Indianapolis 500. Drove 370 miles and his car finished 13th in the race. Again, with Lee Frayer, they shared the ride.

Then in 1912, again, he drove his [00:38:00] relief, but the company was nearly bankrupt. So he left the Columbus Buggy Company. At the time, he wanted to be a professional racer, so he went and did that. The only problem was he had been barred by the AAA because he had been racing in a lot of unsanctioned races and they didn’t like that.

The interesting thing was the contest board that barred him, he was the head of that contest board from 1927 to 1946. In late 1912, he went to Des Moines, Iowa, and began working for the World’s Fair. Duesenberg Brothers, who had located there, is a 3 a day mechanic, and he was also their racing manager for the Mason Automobile Company.

This is how they got their start involved in racing, but racing, Masons worked well for the Duesenbergs and for Rickenbacker until the Mason Company decided they were going to get out of racing. So what do they do? Duesenbergs decide we’re going to start our own company. They did this in [00:39:00] 1914. They made Eddie the head of their racing division.

They had two cars in the first Indianapolis 500. They performed well. Eddie won a lot of races, including the 300 mile race at the Sioux City track, which was a two mile dirt track. And it was one of the biggest races of the 1914 season. He won 10, 000, which at the time was over 250, 000 in our money. And this was actually what saved the Duesenbergs from going bankrupt.

After the 1914 season, he went to the Maxwell team. He won many races with that, including several board track races. And Maxwell was getting out of racing. So he bought the racing cars from Maxwell with the help of Carl Fisher and Fred Allison, the Prestolite company and named them the Prestolite specials.

And with those cars, he won a lot of dirt races and he won three major board track races during 1916, as [00:40:00] well as racing and dirt and road races. The board track races he won were at Sheepshead Bay at Des Moines and a 300 mile or at. Tacoma. This is where he was being honored. And that’s the car that he won the Tacoma race in with a riding mechanic because that was the rules of the time.

And then his last win was at 150 mile race at the Ascot Speedway in California, which at the time was a mile track. That was actually the end of Eddie Duesenberg’s automobile racing career. He had 41 national championship races, seven victories. And he also in 1916 won 60, 000 as an automobile racer.

Today, that’s about a million and a half dollars. So he was very successful. He joined the air force after that first started as the driver for blackjack Pershing, then got into the air service, wanted to start an air division with former racing drivers, but they, for some reason, didn’t want to do that. He became the Ace of [00:41:00] Aces, 26 victories.

That’s one of the aircraft, the Scout, the SPAD that he used. And then later in the 1930s, he was awarded the Medal of Honor for his service during World War I. But here on this particular day, they’re honoring Eddie Rickenbacker. Notice the other names. Louis Chevrolet, Dario Resta, Eddie Hearn, Cliff Durant.

Ralph Mumford, a major sports personalities in automobile racing. Here’s Harry Hartz and Harlan Fangler. Harlan Fangler, of course, for years was very involved in the Indianapolis 500. Harry Hartz was 1926 champion, an exceptional board track racer. This is a 1922 Dursenberg that raced in the 1921 French Grand Prix.

That was the first French Grand Prix after World War I. And you see the number on the tail. The laws at the time required any vehicle on the roads in France to have a number. 1924 Duesenberg was the first American supercharged race car, just to see how it’s developed over the years. Talk about board [00:42:00] track racers.

These are two ads from the 1920s. And these people were equal to Jack Dempsey, equal to Babe Ruth, as far as being stars. Notice the picture in the center, Fred Wagner, he was the official starter for all the board track races. He was the official starter for all the AAA races, but he was as well known. as the people who were the racing and the racetracks where they race.

Here is a late 1920s ad. Again, the Dusenbergs were interested in selling automobiles. They used racing to do that. And here’s an ad showing all the various ways that the Dusenberg was a outstanding vehicle for its chassis, its driveline, and its engine because that’s what they were selling the people.

How would you let your people know about it? Well, that left panel there shows the handouts that were given and it’s the Atlantic city motor speedway, their first race. And there’s a guarantee and the top left that says these races aren’t fixed. This isn’t hippodrome [00:43:00] because in the early years of automobile racing, especially the international motor contest, this is, these would go around the tracks.

And they would have races and they would promote this driver. Let’s see if he can win here. And there’s the battle between this driver at driver. Well, these were all races that were already picked and they were just seeing something on the racetrack, but they guaranteed you that these were races. That were true races, national and international speed king.

And these were handouts. All the tracks had these particular things. Media was very interested in auto people racing. You can look through and see some of these things like this magazine. Look at the artwork on the front of the board track. there. This was something that attracted people’s attention. The newsreels, you can go on the internet and see newsreels of board track racing because they were photographed, there were excitement, there were speed.

Also, entertainment used board track racing. One of the early movies that Charlie Chaplin made was of an automobile race. Why? A lot [00:44:00] of people there. It was in the daytime because that’s how they filmed things. They didn’t have studio work. They had to be out. where there was bright sun. So they used racing as something that people were interested in.

The Roaring Twenties was a great time for automobile racing. Here’s some modern mechanics and inventions. We probably know that as Mechanics Illustrated. This is the beginning of Mechanics Illustrated. This particular man, Ray Kuntz, was a automotive engineer and is identified as an authority on automobile racing.

He’s encouraging young men to become automobile racers. He’s telling them how much money they can make, how easy it is to convert a model a or a model T into a racing car. He even in the article tells you some of the parts that you need, how much they cost, how easy it is to build, how many of us wanted to be racers when we were kids, how many of us had our parents say, yeah, Herbie, go ahead.

I don’t think too bad, but that’s what it was in the twenties. Here’s a [00:45:00] pamphlet that Arthur Chevrolet offered for 2, or if you brought a Fondi head, you got it for free. It was an eight page pamphlet with no photographs in it, but it told you directly and entirely how to convert a Ford Model T into a winning race car, what you needed, how long it had to be.

The first thing was to take the chassis at a hundred inch wheel base. The first thing he said was you make that 88 and it told that, and it was very popular. Here’s another example of advertisement. You could buy like you can today. You can go to anyone by modified stock car for parts, put them together like a giant model kit.

Here you could build a racing car. Out of a Ford that was good on dirt tracks, brick, or board tracks. 750 for a complete frame. That would be about 10, 000 today. This will give you an idea of the cost of these things. And this, I’ll tell you a little interesting story. I wanted to say how are we going to relate this to what’s today.

So, well, let’s say [00:46:00] 1925, that would be a good year because of a couple of things. Let me see what the average income was in 1925. So I typed in the computer, average income, 1925. 14. 40 was 3, 078. 27. Good, now we’re going to have to compare it to today. So I figured, let me try, see what average income 2018 figure gives the whole year.

Boy, that was a chore. No matter what government site I went on, they talked about average income for people that were particular age, average income for people in the Northeast, average income for people in the particular state. I’m sure if I looked hard enough, it would have average income for people who are blonde, left handed, and wear green shoes.

It was just that difficult. The average income today For all of us, somewhere between 50, 000 and 52, 000, according to the U. S. Department of Labor. That was at the bottom. But look at the prices! Pound of [00:47:00] bacon, 0. 47. That would be 6. 70 today. And you can see down the side. Postage stamp, 0. 02. The only thing that’s interesting about all of these As you see, a gallon of gas costs 2.

88. In town, they’re selling, what was it, 2. 69. So we’re doing better now than in 1925. But you see here, 1925, that was the first year for the front wheel drive Miller. And the front wheel drive Miller cost 15, 000 in 1925. That’s 216, 000. A Ralph De Palma, 10, 000. That’s 144, 000. These prices did not change from the first made until the time they were ended.

They all stayed 15, 000 or 10, 000, which I thought was very interesting. And in 1925, if you wanted to buy a Model T, it only cost you 260. So you can see there was a wide difference in the cost like there is now of racing cars and a [00:48:00] Miller engine. If you blew your engine. 5, 000, which is 72, 000 in today. So that gives you a little idea of what the money values on these things are.

Here is the Miller specifications. I would point out that the fuel tank came in the Miller 25 gallons, but for longer races, they would put in up to 40 gallons. There was even one racer and I forget who it was who had a round. Tank like a giant basketball. So all the fuel would get down. There wouldn’t be anything laying around, but you see the workmanship.

These are just beautiful cars. This is what got me interested in these cars. I saw Miller’s, I saw pictures of Miller’s and I just thought they were. Beautiful. Notice the engine size 1920 to 22 was 183 cubic inches or three liters. That was when the AAA contest board decided to change the engines because they were going to be the same as the international limit on engines due to the French Grand Prix.

That’s how three [00:49:00] liter engine, and then they went down. And so like that, the bottom is a engine tag. It gives the firing order of the engine that. Harry Miller developed. All hand built, just beautiful racing cars. Notice the tire sizes, too. And here’s Jimmy Murphy, who was an outstanding board track racer, king of the boards.

He is the person who decided that it might be an idea to try a front wheel drive car, to pull the car through the corner, rather than push it through. He thought it would be, engineering wise, a better thing. And he had Harry Miller build one of these things. Unfortunately, Jimmy Murphy never got to drive that car.

He was killed at Syracuse in an accident going for the lead. That was in 1924, so he never got to drive this car. But this car appeared for the first time in the 1925 Indianapolis 500 and finished second, driven by Dave Lewis. And they were very popular, very fast. The interesting thing about the Miller, as though it was a good idea with the front wheel drive, the [00:50:00] Miller, A front wheel and rear wheel drive car won about the same amount.

Front wheel drive car was only a car that raced at Indianapolis and the board tracks. It did not race on the dirt tracks at all. The nine, ten years of board track racing, they used regular street tires. Whatever was on the car was what they used, and of course they caused problems. Gum dipping was a procedure to keep the heat away from the tire, but they were street tires.

And as wide as your hand, they weren’t very big at all. And they were inflated to 50 pounds. This was a hard, hard tire. Then in the 20s, they started making dedicated racing tires because they understood the problems they were having. At Indianapolis 500, you’d maybe go 10 or 15 laps in these tires and have to change them.

So that’s why they had the dedicated racing tires. And they started to balance tires. Sid Huggdahl was the first racer who balanced tires to get better wear out of them. This, again, was in the 1920s. In 1925, Firestone introduced, for the [00:51:00] highway, the balloon tire. Better traction, better handling. It was cooler.

Did all the things it wanted to do, and they developed from that. The Firestone Gum Dip Balloon Racing Tire was introduced in 1925. It won with Peter DiPaolo. Bigger cross section. Contact patch was bigger. On dirt tracks and at Indianapolis, 35 pounds on board tracks, 65 to 75, the high speeds and the high G forces in the turns, they needed something to stabilize the cars a little bit better, get a little more speed out of the wire wheels.

And so board tracks, they ran with a toe in of 1 8th to 3 inch because the high speeds would open the wheels up. On the lower size tracks, on the dirt tracks, they would run with a tow out because the speeds would push the tires in, so that was just a little bit of difference there. Also, the reason I used the Oldfield tire was, Barney Oldfield, when he retired from racing, became the firestone manager of racing.

And [00:52:00] the 1920, Indianapolis 500s, you may see in Historical ads are credited to being won by Firestone, which is true because Firestone made the Oldfield Tire and the cars that Tommy Milton, Gaston Chevrolet, and Jimmy Murphy rode in those Indianapolis 500 wins are all Oldfield Tires. And if you look closely at the pictures in the winner’s circle, you can see it says Oldfield Tires on their race car.

So the first. Three years of Firestone’s wins in that long series were on Oldfield Tire. Here’s an interesting track. This is the one in Miami, Florida. Mile and a quarter, Fulford Miami Speedway. Carl G. Fisher was developing Miami. He also had a board track down there. His general manager was Ray Haroon.

And the track ran one race. Won by Peter DiPaolo in the Duesenberg. Harry Hartz and the Miller. Not long after this race on February 22nd, the great hurricane [00:53:00] in September of 1926 came through. And that’s a picture of the racetrack after the hurricane came through. Absolutely destroyed it. There was nothing that was left of it.

All that wood was used to rebuild the Miami area. Board track events. Here we talked about some of this varied length. races, things like that, things to get people to come to the races. There was one 500 mile race. The lineups were cars that were developed by the manufacturers. 1920, 1931. This is when it became more of a dedicated racing series.

All of the national championship were on board tracks. There were still other kinds of racing, but they were mostly millers. and Duesenbergs and the Fronty Fords and the Frontenacs were 1920 to 1924 because those engines did not ever have a supercharger on them. The other interesting thing about the 20s to 1931, mostly during this time, numbers were assigned to cars based on the decision of [00:54:00] the contest board or how the car was entered into the race.

1924, that was the first year they assigned numbers based on how you did. The year before. So if you see a 1925 picture with number one, that car was the winner of the championship in 1924. Here’s an official program showing Barney Oilfield and Louis Chevrolet special race. There’s the Los Angeles Speedway, that was the Beverly Hills Speedway, but that was also known as Los Angeles Speedway.

The reason I put this on here, 1928 State fair, this was the year that board track racing was really on the way down. So the AAA contest board decided that dirt be brought into the old, as far as national championship races. That’s how this became the first national championship dirt race in a long time at the state fairground.

Stock car races were special things. They see the number one and the two, they are actually cars that could have been driven to the track because stock car racing [00:55:00] was just what it said. Stock car racing. Notice the spare tire, the windshields. The headlights, that’s what they raced. They were specialty races.

Also, motorcycles ran on the board tracks, and I say those people just did things differently. A lot of accidents and so, but they used them. The bottom picture is what is considered by historians as the first real stock car, in the fact of a racing stock car. In 1933, the AAA sanctioned its first road race, which was the Elgin Road Race in Illinois.

And Fred Frame, one with this car. Notice there are no fenders, no windshield, no spare tire. There was a little bit of work that could be done. So this is what they consider the first stock car built. And this car is currently owned by Dana Mecham of the Mecham Auto Auctions. Louie Meyer. In 1985, I had the opportunity to write a story about him and spoke to him for over an hour about automobile racing.

Wonderful man. Everyone I’ve talked to who’s known him. And I’ve [00:56:00] talked to several people, said he was a gentleman, and that’s how he treated me. He won three board track races. He started as a mechanic and then to a driver, then became a Indianapolis 500 winner and champion. He had the Meyer Drake engines for a while, then he had the Ford racing engines.

And this is his 1928 Miller that won the Talked to him about a lot of things, and when he said he wanted to be a board track driver, Pop Wagner said to him, Okay, you get out on the track, but if you pass anybody, I’m going to flag you in. There was no other way to learn how to drive, so you had to drive around the back to learn.

And he became very adept at it. And I asked him, well, who are some good board track drivers? And you say, Hartz, Leon DeRay. A lot of them, he said, but Frank Lockhart, he said, was just very good. And Frank Lockhart was maybe one of the best race drivers and engineering people that we have ever dealt with.

This car was the car that Frank Lockhart set a world record and that stood for 30 years. Fred [00:57:00] Wagner, he was the starter for all the board track races. He was the official starter for AAA for over 20 years. And he started out to be a runner. And then he started flagging, getting involved with that.

Interesting that he holds the checkered flag. He’s the first person to ever be photographed with a checkered flag is in the 1906 Vanderbilt cup races. He also not only was. He was the man who checked the track for security and safety. He was the man who got all the money before the races started. He was the man who assigned positions.

He was the man who would call fouls because they had no communication. Something happened on the track, he was it. He was the man at the end of the race who would tell you where you’re going to pick up your train to take your trip to the next race. He would get housing for the people. And in his spare time, he wrote a nationally syndicated column on automobile racing.

But the most interesting thing about all his involvement with automobile racing, he [00:58:00] didn’t know how to drive an automobile. Here are the signals that he would wave. True 1929, this was about standard. Here’s the official thing from the AAA handbook. Red, that meant the course was clear. That’s how they started the race.

Yellow. The course was blocked. You slow green. You are entering your last lap white stop for consulting and the pits and the checkered flag. You are finished. They changed it in 1930, the triple a contest board, because they wanted to be a little more current. That’s when the traffic signal said red stop, yellow caution, green go.

So they changed those signals. Although notice, the white still meant stop, and the black was added, which means you were entering your last lap. That was in 1930. That again was changed in 1937, for the white meaning you’re entering your last lap, and the black flag meant that you were stopped. And since, that’s been basically the American racing flag.

Here’s a map that shows where the [00:59:00] tracks were during their lifetime. And it was interesting that Louis Meyer told me he and his wife would travel from Los Angeles, where he lived, to Indianapolis, because that was the center location for all the racing. But he only covered about a hundred paved miles during that entire trip.

Everything else was gravel or something worse. He’d stay at a farmer’s house for a dollar and a half, get paid. Big breakfast and they’d send you on your way. Racing, you would stay at a buddy’s house if you were at a racetrack and so. All the cars were shipped by rail. Atlantic City was interesting because they had two rail lines into Atlantic City because during World War I, the location of the Atlantic City track was a ammunition loading plant.

Here’s how cars got to the racetrack. This is a 1917 Hudson. This was a dark blue car, by the way. And this also made it possible for races to be announced at major locations. They came on railroad cars. When they got to the station, leave them out so the people would know there’s a race in town. The bottom is Umbrella [01:00:00] Mike Boyle, who was a Indianapolis car owner.

He was the head of the Chicago Electrical Union. And they used the, uh, Diamond T truck to get it from the railroad station to the track. Mike Boyle was an interesting guy. They called him Umbrella Mike because he always walked around with an umbrella. Mike would go in a bar and he’d talk to people and they’d come by and they’d drop a little something into the umbrella.

And Mike had connections. In Chicago, in 1920s. If you needed something done, you saw Mike. This is William Shattuck, who was a pulmonary physician, an actual MD, who became a race driver because he enjoyed working with the people when he was a physician at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. And he bought a car and he raced in 35 events.

Never won one. But he was competitive. He was a relief driver at Indianapolis. He just had some fun doing it. Probably heard a lot of you. I’m sure of Leon Duray, whose actual name was George Stewart. But when he was racing with the international motor contest association, he wanted to be the dashing Frenchman.

So he would [01:01:00] dress in black and his hair combed back. And this worked fine until the French attache in New Orleans wanted to meet the great French driver. And Leon didn’t speak any French, but he was very fast and he was early working with alcohol fuels because the engines were supercharged and needed the power.

And also he eventually became a car owner at Indianapolis. But he also went in 1929 with that front wheel drive car. Sent many records in Europe and also raced in the Italian Grand Prix in Monza. Here, uh, just briefly is the Atlantic City proposal to build the track. You can see how much they were expecting to make.

Cost, the lumber, they actually used over 5 million board feet of wood. This was about a 6 million dollar job in today’s money. And the people who ran this, they were investors of wealth, rich sportsmen, business tycoons and so. Here’s the Atlantic City track. This is opening day. Far picture on the left is [01:02:00] 1926.

This is a rather recent overhead picture of the track. Because this was an ammunition dump and all the chemicals and stuff, they used it when the property was no longer used. The state of New Jersey allowed it to just grow up. It’s now a wildlife area. Terry and I were there a couple of years ago. It’s one of the few former sites that has nothing on it.

There is not even a marker to indicate the history of that track, which had the ammunition dump or the racetrack. But, that’s the way things are. Here’s Harry Hartz, who won the first race, non stop, 300 miles. He won 12, 000 then, that’d be 171, 000 today. Just amazing. This is the official report. Notice they have when the tires were changed, right rear.

Left rear. Things like that. This record that Harry Hart set in that first victory of his lasted for over 30 years. He went 135 miles an hour for his 300 mile race. No one in America ran a [01:03:00] faster race until Sam Hanks won the Indianapolis 500 in 1957. Harry was the National Champion in 1926. He was in a bad crash, spent two years in a hospital, walked around the rest of his life with a cane, but he was very involved in the Speedway and the Technical Committee.

1927, Frank Lockhart set a world record that also stood for over 30 years. It went 147 miles an hour around 729 miles an hour around Atlantic City track. This is a picture of him setting that speed record. This is a qualifying record that was not broken for over 30 years. Leon DeRay in a front wheel drive Miller at the Packard test track went in 1928, 148 miles an hour, but that wasn’t a qualifying record.

So it was, you know, apples and oranges. Notice he has a air intake in front of the cow. This is the engine he did it with. This was an invention that he made with the. A couple other engineers. This was the Intercooler. When the air came into the supercharger [01:04:00] while it was being supercharged, the air fuel mixture was over 300 degrees.

Going through this intercooler before it got into the engine, lowered the temperature by 200 degrees. It went from 300 to 100. This made all the difference. He said this was an oil cooler so people wouldn’t know what it was. Leon DeRay was the next one to make one. Used it on the front wheel drive Miller, but the U shape, it was a five piece unit.

They used gasoline and benzoyl to help power it a little bit more, because the compression was so great on these engines anymore, they needed more than they could get. The first 100 octane fuel wasn’t until 1934, when Jimmy Doolittle with Shell Oil Company made the first aviation fuel with that. level.

Here again is the report of that race. The yellow I outline this tells about the speed record that he sent at the bottom. It shows his speed 147. 729. Cliff Woodbury was second fastest that day. He was almost four miles an hour slower. Here’s the tires that they [01:05:00] used. Notice the pressures were very high.

The sizes. Each race they identified the tire being used by serial number. This was part of the official records and they show what happened and how people went out of the race or something broke, someone ran out of gas, non stop, things like that. Atlantic City Speedway was also known as Speedway, New Jersey.

That was in the official records. They wanted to do that and promote it because although it was listed as Hamilton, it was actually in a township and they wanted to make something else like Indianapolis, which is actually in Speedway, Indiana. And sometimes it was called Amatol because of the ammunition plant.

Here when Lockhart set that record, the speed at Indianapolis was 113 miles an hour. Tony Bentenhausen was the man who broke Lockhart’s qualifying record, 176. 830 at Monza when they had the Race of Two Worlds. Then George Amick broke what was then the American record at Daytona. He unfortunately was killed [01:06:00] in that special 100 lap race.

It was the only Indianapolis car race at Daytona. And then the first time that someone went faster than Frank Lockhart at Indianapolis was when Jim Hurtabees. Went 149 miles an hour in 1960. The last board track winner was Shorty Catlin, and that was at Altoona. Altoona was the longest living board track.

It was there for longer than any other. Woodbridge was one of the small half mile tracks. The last winner was Burt Carnance. That’s the site of the Woodbridge High School football stadium. So that was one of the ones that lasted through. And here are your top board track winners, Murphy, Milton, you see all names that you remember.

Thought I’d highlight Tommy Milton for a minute because of his 50 board track wins, land speed records, Indianapolis, all the things he did. He was 100 percent blind in his right eye and had limited vision in his left. And there he is in the Miller. Here, Gaston Chevrolet when he was killed. This was a major, major event.

This was a dangerous sport. There’s no question [01:07:00] about it. They’re going so fast and what they’re going in. And how they’re doing. Eddie O’Donnell and he crashed. One of the mechanics was thrown out of the racetrack. The color panel shows this. And the reason this color panel was drawn was because Gaston Chevrolet actually believed he called his brother Louis and told him I, I’m going to die here.

And Lewis said, no, you’ve been successful at that track. You’re going to retire, race one more race. You’re going to be the national champion. That was it. Here is the national story that went out about this. It’s very graphic, very graphic, but that was 1920s writing. Here is a picture of Eddie Rickenbacker.

Notice the football helmet. That’s a picture taken in 1914. He was maybe the first to wear head protection other than the flight helmets that they wore because they had nothing else. Helmet, goggles, and gloves. That was all the protection they had. Here, unfortunately, a list of the people who were killed in board track racing.

It was a different time. These were different people. Factors that influenced the board track. The automobile industry, as we [01:08:00] talked about it, was developing the car, the high speed. Major business people, Firestone family invested in board tracks. The Ford family invested in board tracks. Thomas Edison invested in a board track.

So did Louis B. Mayer because the Culver City track is built right up against the back lot of the MGM studio. Automobile race in a major sport communities wanted to have it increased the value of the community and get people to help the economy. And these people were major racers. What caused the demise?

It cost a lot to maintain something that wasn’t protected by anything for the weather, plus the recertification that may cost a hundred thousand dollars to put new wood down when they needed it. Lack of competition. Louis Meyer told me the fastest car always won because it was just speed. There was no way for a slower car to, uh, get around a faster car, weather damage, dwindling attendance, because people Oh, okay.

Yeah, we saw that. It’s not continuing to be. And then, of course, the Great Depression. [01:09:00] Here’s a postcard of the Charlotte Speedway. Interestingly, they had two or three stock car races there that didn’t draw any attention at all. Now you go to Charlotte, that’s all they have. After the board tracks, there was nothing till the Nutley Velodrome and some other places raced midgets on these tracks.

You couldn’t get a championship car on that. They were too small. Seventh of a mile, you have four or five championship cars on there. They’d be nose to tail. But the velodrome ran for a couple of years, very successful. But also they had three fatalities. The New York newspapers just were out against this kind of thing.

That’s Tommy Heinrich. It’s leading this group of people. You figure seventh mile track. They’re going around seven, eight seconds, 70 miles an hour. That’s really doing something. And that’s Henry Banks who became a director of competition in Chicago. They built a board track for one use. Cost 25, 000 then, almost a half a million today.

This was for the world championship at 90, 000 people see this race. And it was for one race. This was at the polo [01:10:00] grounds. This was a high bank board track. It was supposed to be run for several weeks, but every time they had a race, it rained except for two times. And what they used to make this board track was a portable board track.

This was an article in 1948, Popular Mechanics, about this board track. Someone got the idea. We can have automobile racing all over the country, wherever you want it. Pop it down, have your race. The promoter was a millionaire sportsman. They had people who were involved, National Midget. The designers, Leon and Lionel Levy, were architects who developed horse racing tracks, boxing arenas in baseball and football stadiums, things like that.

All of this with a steel underpinning, it was like putting a big model kit together. You transported it from place to place. Cost 150, 000 then just for this. Million and a half today. But the transportation and the labor was extra. They ran it a couple times in the polo grounds, then it was shipped out to the Rose Bowl.

[01:11:00] Rose Bowl and Los Angeles had board track midget racing. Problem was the tracks were too narrow. No activity, no action, because they had had dirt midget racing at these two venues. They tried this to think it would be better. It wasn’t. That was sort of the end of board track racing. And I’ll end with this.

Here are two interesting books. Both are still available. Although they’re not new books, they’re used books or something like that. Although the Wall Smacker, which is Peter DiPaolo’s autobiography, you can get in an e book, tells all about the board track era. That Guts and Glory that Dick Wallin produced in 1990, I wrote two chapters in that book.

I would have written it differently today than I did then. Because of the internet, you can find out so much more information than going to the libraries like I did. Plus, there are other books. Griff Borgeson has the book about the golden era of auto racing in the 1920s. And Mark Dees excellent book on the Millers.

These give you some insight into board track racing. [01:12:00] Ladies and gentlemen, I, I hope I’ve piqued your interest anyway. And, uh, I’m just proud to be able to address this group. And board track racing is something that, uh, Happened a long time ago, but it’s a major part of American history and I hope you enjoyed it.

Thank you.

This episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center. Its charter is to collect, share, and preserve the history of motors, sports spanning continents, eras, and race series. The Center’s collection embodies the speed, drama and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world.

The Center welcomes serious researchers and casual fans alike to share stories of race drivers, race series, and race cars captured on their shelves and walls and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events. To learn more about the Center, visit www. racingarchives.

org. This episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of [01:13:00] automotive history. The SAH actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers. Organizational records, print ephemera and images to safeguard, as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding of motorized, wheeled land transportation through the modern age and into the future.

For more information about the SAH, visit www. autohistory. org.

We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Brake Fix Podcast brought to you by Grand Touring Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at GrandTouringMotorsports. And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article at GTMotorsports.

org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as 2. 50 a month, [01:14:00] you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional Pit Stop minisodes, and other VIP goodies.

As well as keeping our team of creators fed on their strict diet of fig Newtons, gummy bears, and monster. So consider signing up for Patreon today at www. patreon. com forward slash GT motorsports, and remember without you, none of this would be possible.

Transcript (Part-2): Stephen Bubb

[00:00:00] BreakFix’s History of Motorsports series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argettsinger family. Well, my name is Kip Snyder. For those who may not know, I’m the Visitor Services Outreach Coordinator for the International Motor Racing Research Center.

And I want to welcome you all here. Thank you for taking a little time out of your afternoon to come visit us. As we talk about open wheel madness, before we get going, I have several people I need to thank on this. First of all, and foremost of all, our two speakers, Mr. Herb and a store and Steven Bob, when we were considering.

Putting this program together, I emailed Lenny Sammons from Area Auto Racing News and asked him what we were projecting to do and who might I get that would be experts in their field and, and Mr. Sammons immediately suggested Herb and Steve. We are very happy and very honored to have them here today. I am personally fascinated at both of the things they’re going to talk about.

Stephen’s going to [00:01:00] talk about sprint car and open wheel racing in the 20s and 30s and some guy named Al Capone. And what he had to do with racing. And that was the hook that got me psyched on his talk as well. So I certainly want to thank both Herb and Stephen for coming here. Yes. Thank you again. Uh, we’ve certainly enjoyed our presentation and I’m looking forward to what Stephen has to say.

First off, it’s going to be really tough to come up after Herb. That was excellent. My name’s, uh, Stephen Bubb and it was really great to get back up in this area. My high school years, I lived across the state line in Tawanda. I worked for a gentleman who owned a number of tree farms, including one in Dundee, New York.

So I’d have to come up here and spend some time in Dundee working at his, uh, tree farm. Unfortunate thing was on Fridays, I’d have to go home. So I have to go right past Dundee Speedway as the race cars were going in. Always tough to do, being a real true racing fan. Little background, I am from the Harrisburg area.

I live Right across the river from Harrisburg. Have a fortunate spot because we’re right in the middle of a racing hotbed down there. From my [00:02:00] house, the wind’s blowing right. You can hear Williams Grove Speedway running. You can hear Susquehanna, which is now BAP Speedway. You can hear that track running.

I am the, uh, librarian at the Eastern Museum of Motor Racing. I’ve been retired from work for about a year. I worked in Pennsylvania House of Representatives on staff, and that is why I don’t have any hair. Because if you work with politicians for 30 years, you lose a lot of hair. And I am really glad I got retired.

Did a lot of things in motorsports. I was a corner flagman. Assistant Flagman. I’ve worked on pit crews, done scoring, been a head scorer, been a publicity director at Williams Grove Speedway for a while when they had the Saturday Night Series. I’ve been very involved in racing, working with the Eastern Museum of Motor Racing as a librarian, which has just been absolutely fascinating.

Any museum, like the museum you have here, is a treasure. I hope everybody appreciates what you have here. Each museum, they’re priceless, and what we’re doing to save racing history, [00:03:00] we have to do it, because so much racing history is being lost every single day, and we have to preserve every little bit of it.

So, I’m gonna be talking about 1920s and 1930s racing. The United States entered the 1920s, having just come out of World War I. 1920s, The American public was hungry for entertainment. Leading the way in summer sports was naturally baseball. Also attracting plenty of the public’s attention was automobile racing.

Automobile competition was going through its growing pains as it ended the 1920s. Tracks were plentiful as horse tracks dotted the countryside. As 1920s racing began, there were two basic forms of dirt track competition. There were the stock cars, the road cars of the day. The second form was the engineered machines constructed for the speedway.

Now this is Speed Gardner’s car. This was from the 1920s, I believe it was 1928 that this photo. The second form is of interest. Today we call them sprint cars. A look at the history of the sprint [00:04:00] car shows the name came about late 1950s, 1960. Prior to that time, they were known as big cars. This leads to an interesting discussion that was recently occurred.

Racing historians go with what I term the Chris Economacky rule. Economacky, the dean of motorsports, said the term big car came with the arrival of midget racing. When midgets burst upon the scene in 1934 and 1935, promoters began referring to the other racing cars This was shown to be true in advertising from the mid 1930s.