Trevor Lister in his retirement, he assumed the role of editor of the newsletter of The Classic Motor Racing Club of New Zealand. That is when, searching for newsletter stories, he came across the work of Donald Capps, and their common interest in old Maseratis. The upshot of working together on the histories of these cars became the main point in the presentation to this symposium.

It appears that Maserati in the 1950s identified their competition cars by their engine numbers, not their chassis numbers, and that this process allowed for the individual cars to have carried more than one identity. This has implications for the provenance of these cars.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience. And has been Edited, Remastered and Produced in partnership with the Motoring Podcast Network.

Bio

Trevor Lister entered the University of Canterbury on a public service scholarship, graduating with a double degree in Physics and Mechanical Engineering. On graduation, he worked in the Ministry of Transport in the setting and administration of Motor Vehicle Safety Standards, primarily on natural gas and LPG vehicle standards. This led to a secondment to a national research and development organization where he was responsible for research on a wider range of alternative motor vehicle fuels. It led also to an international consultancy in that area, including a stint as the New Zealand delegate to the International Natural Gas Vehicles Association.

Upon completion of that work, he returned to his foundation automotive design skills and his motorsports hobby. At which point he became an inspector and certifier on other peoples’ projects, as well as designing, building and racing his own cars. In semi-retirement, he took up teaching and tutoring pre-apprenticeship students in Mathematics, Science and Automotive Engineering.

Slides

Swipe left or right (or use the arrows/dots) to navigate through the presentation slides as you follow along with the episode.

Livestream

Transcript

[00:00:00] Break/Fix’s History of Motorsports series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argettsinger family. Truth is the Daughter of Time by Trevor Lister. Trevor entered the University of Canterbury on a public service scholarship, graduating with a double degree in physics and mechanical engineering.

On graduation, he worked in the Ministry of Transport in the setting and administration of motor vehicle safety standards, primarily on natural gas and LPG vehicle standards. This led to a second bent to a national research and development organization where he was responsible for research on a wider range of alternative motor vehicle fuels.

It led also to an international consultancy in that area, including a stint as the New Zealand delegate to the International Natural Gas Vehicles Association. Upon completion of that work, he returned to his foundation, automotive [00:01:00] design skills, and his motorsports hobby, at which point he became an inspector and certifier on other people’s projects, as well as designing, building, and racing his own cars.

In semi retirement, he took up teaching and tutoring pre apprenticed students in mathematics, science, and automotive engineering. In full retirement, he assumed the role of editor of the newsletter of the Classic Motor Racing Club of New Zealand. That is when, searching for newsletter stories, he came across the work of Donald Capps.

and their common interest in old Maseratis. The upshot of working together on the histories of these cars became the main point of the presentation in this symposium. It appears that Maserati in the 1950s identified their competition cars by their engine numbers, not their chassis numbers, and that this process allowed for individual cars to have carried more than one identity.

This has implications for the provenance of these cars. All right, folks, next up is Trevor Lister, and Trevor’s giving a talk at much of the [00:02:00] research shared with Don Caps. Truth is the daughter of time. Good morning to all my old friends in the, in the glen. Been a while since I was last there, especially if Donald Caps is, uh, is in the audience, a big hello, Donald.

Thank you very much for your support over the years. I will be talking today on what might sound on a little strange approach to vehicle identity, old Maserati specifically in the 1950s. I’ll be looking at the, uh, different ways in which a vehicle can be identified and what that might mean for the provenance of the vehicle.

A little story perhaps about an Englishman, an Italian, and an American who met in a bar and started discussing, uh, identity of the vehicles. The Englishman would say, all of chassis is the most important part of the vehicle and it’s the chassis number that sets the identity for the vehicle and it’s that identity from that point on until the day it gets put on scrappy.

The Italian [00:03:00] would say something different, and then so Ferrari did back in the 1960s. He said, I don’t sell cars, he said, I sell engines. The car is only there, he says, I throw it in for free because something’s got to hold the engine in. Quite a different approach entirely. The American was probably Bob because he was a, uh, the, the story I’ve got here is kind of coming from a Ford perspective, Henry in the 1930s would identify the vehicles coming down the production line were identified according to the engine number.

Imagine yourself at a very busy plant, the engine is just being passed through it. So. Pre run testing. It’s just about to be placed in the vehicle. It has a gearbox attached to it. The gearbox gets stamped with the engine number. Then bodywork, uh, gets applied. And just before the bodywork gets done up nice and tight, the, uh, engine number is stamped on the frame.

Nice and simple. The engine sets the identity of the car. A little further on that one and say [00:04:00] that initially there is a wee twist if it’s a, uh, Enzo talked about production cars as well as race cars, but at Maserati, if a engine and a race car was changed, then the identity of the vehicle was changed to match the, uh, Engine number, and as the engine number didn’t just set the identity when it first rolled off the production line, it was quite capable of changing and giving a different vehicle identity as the vehicle was raced, either race to race.

Chosen this car as an illustration of what happened at Maserati because it’s a very rich car in terms of its background and its provenance. If you look at it on the slide, it looks like a pretty much like a standard 1950s Maserati Formula One car, but in fact it is not. It started off as a two litre Formula Two car and it had a identity number given by its engine of 2038.

That was its first identity. The very early part of the 1954 [00:05:00] Formula One, uh, racing season, the cars were in Argentina. Maserati had a lot of 250 F, uh, Formula One car, but unfortunately it could not supply, uh, every customer at the same race. So some of the Formula Two cars were adapted to Formula One specification by putting a bigger engine in and, uh, running them as Formula One cars.

This is one of those cars. When it got its Formula 1 engine, replacing the old Formula 2 one, its identity changed to match the new, larger engine. In that guise, this car was known as 2 5 1 0, and that wasn’t the end of its identity. The following year, it was bodywork revised, which is why you see the The lovely, uh, 250F type bodywork on it in the photograph, it’s engine was changed once more.

It now got engine 2518 and it took on identity 2518. So if we trace this car right through, we see, uh, three identities all [00:06:00] set by the engine that it was carrying at the time. And it doesn’t stop there. The interims, there are four of them all together. They all had that same pattern that giving up their old Formula 2 number and adopting the, uh, Formula 1 engine number.

Each and every one of them followed exactly the same pattern. So, um, Council were looking at the interims to say that, yes, that’s, um, Harigot. The Maserati was obviously, uh, uh, identifying according to engine number. And if the engine went to another vehicle, it would carry its identity, take engine identity with it.

So far, so good, except in England, they didn’t do that. In England, there was a lot of interest in Formula One, of course, it’s just getting to the point where England was ready to start dominating Formula One in a year or two’s time. And the English commentators were very keen on pushing for the chassis number to be the one which identified the car.

This might be sad in England, but it’s not so. Everywhere else, unfortunately, the English men did most of the [00:07:00] commentaries quite frankly. They did it according to the English pattern that chassis number determined the identity. English pattern is strict and rigid that says that’s the identity. It’s the chassis and that’s all that matters.

And that will always be forever. But that approach is no good whatsoever. In a set of circumstances where the engine number will change and the identity will change. And the vehicle may carry three or four different identities in its lifetime, or the same engine may turn up on three or four cars or more.

Which means that when we look at the old commentaries and the identity, we now have another question to ask in terms of provenance. And that question is not, is this the car you think you’ve got? The question now becomes, does this car have The background that you said it was really the car that Fangio used on a particular race on a particular day.

Because if it had multiple identities, we’re now going to have to say which identity on that day was the [00:08:00] one that was used. And that’s the implications for provenance. This car is a, uh, Maserati 250F with a, uh, very interesting, uh, background of provenance. It is actually the, uh, third car of three to carry engine and identity 2504.

The first car to do so was, uh, one of the interim Formula One cars that we saw before. When the customer car was ready, the full Formula One car was ready, the interim was sent back to the factory, and the brand new 250S was given to Prince Beauregard, and he had a great time racing it in the 50s, except he only raced it one and a half races.

He was over at the British Grand Prix and made a deal with the BRM team to, uh, have a second driver drive his car. That’s. Pete Burrow could not do so because of his illness. Halfway through the race, he come in, the drivers changed positions, uh, the B area driver took the, uh, car out, and within two or three [00:09:00] laps, had managed to roll it, put it over on its lid, and damaged the, uh, the car quite a lot.

The unfortunate part was that Burra now had a, uh, a race meeting the following weekend, which would have a lot of starting money, but he had no car to race. So the deal was made with the BRM team that they would swap the engines and the identities into the cars. The damaged one would be retained by BRM and Burra would go away with the old BRM team car, and that’s what he would race.

So it turned out, nobody said anything about it for a long, long time. Car itself was photographed outside. Museum in New Zealand came into New Zealand as CAR 2 5 0 9, which was the BRM team car, but it wasn’t 2 5 0 9 at all Underneath it, it was 2 5 0 4. We checked this out a few years back. Um, by putting a tape measure over it, there was a difference in builds between the 2, 2, 5, 8, 4 was a very early.

And it had a slightly shorter wheelbase and we measured it up and sure enough, the car [00:10:00] masquerading is 2509 in New Zealand for many, many years. It’s actually 2504, third of the cars to carry that number. Uh, and also one fourth one later on also carried the, the engine number 2504 and was also known as 2504.

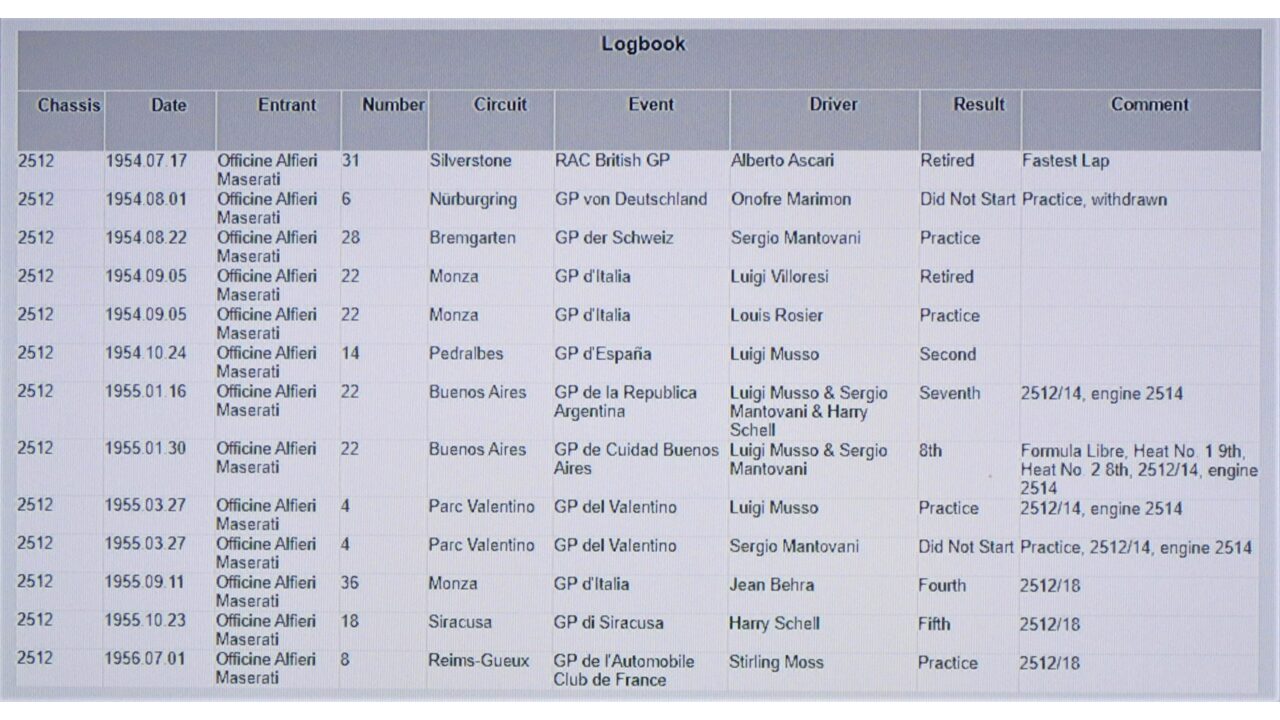

So that’s four vehicles, four engines, one identity, 2504. This rearrangement of identity numbers every time an engine was changed has been around for a long time. The old English commentaries actually noticed that the changes had taken place. They would note, for instance, the car 2512, at least they’re pretty sure it was 2512, turning up the race says 2514 or something, uh, that, uh, would note.

That there was a change in identity, but gave no clue whatsoever, or any thought to why that may have been so. To answer that question, we go to Donald’s database. It’s a very, very large database. Very well laid out. I’ve got to thank Donald for giving me access to [00:11:00] that database a long time ago. Turns up, uh, on his emails, one day, and says, Do you mind if I muck around with your database, and, uh, to Don’s credit, he said, Yeah, go right ahead.

What Donald had done is captured the engine numbers for each vehicle, each car, and each race. And when his database was put alongside the older commentaries, There was a one to one correspondence between what the older commentaries had just noted as This car raced as 251 4, for instance, Donald’s database showed that on this race.

Yes, it did run as 251 4 and that it also carried engine 251 4 for that race. So we were able basically to take all of the old puzzles of identity for the 250 S and as a side issue, every other Maserati as well, that was traced in the 50s. And, uh, solves a lot of old puzzles and problems which had found their way into the audio commentary.

[00:12:00] So we are now quite happy to say that Maserati identified its race cars, according to the engine that was in them at the time. Ask him to have a look at this document you’ll see on Don’s side notes on the, uh, right hand side of the page. Maybe now and again he will note with engine. With engine 2514, for instance, he’s following card 2512, which is a, uh, very interesting little thing in its own right.

To go with, if you wish to continue this with us, we’d be very, very happy to have you do so, because the more attention we put to it, the more accurate we get with our data and our conclusions. There is a set of papers to go with this presentation, and they are available from Bob, if you wish, or Bob will give you that email for me, and you can get them direct.

You have to look at the whole thing and, but it’s only 17 pages long and we’ve got to get there. Dom, nice to see you. How are you going? I’m the one who put this together. So let me try to explain it to you. I am a [00:13:00] trained professional historian. So when I started seeing anomalies in data that I’m digging out of various sources from the archives and so forth, and Trev was pretty clever to pick up with this with me because everybody else thought I was crazy and a complete nutcase.

Let me explain it this way. There is how the rest of us do things. Then there’s the way the Italian automakers do things. Maserati, and I think Travis pretty well hit this. They looked at the motor as how they tracked these cars and that rolled through the racing shop. When he came in, they pulled the engine.

They did all the little maintenance on the chassis. And when it was time to roll it out. They put whatever engine was ready in that car. Now, originally, the chassis and the motor all pretty well matched, but engines blow up, you build a new engine, but you don’t always build a new chassis, or you build a new chassis, put an old engine in it.

That sort [00:14:00] of thing. Dino, Gino, and Luigi, all working in the racing shop, tracked it by the engines. It’s kind of like those of you who can do a calculator, versus those of us who are completely baffled by them because we do scientific notation. It’s that different. They were not like the English, as Trevor pointed out, back when it all starts, it’s all matches.

As I started digging and digging and digging and digging, was here for like 2512. Okay, the English would call it car 2512. Well, when it got engine 2514 in it to the racing shop and to Alfasini Alfieri Maserati, the entrant, it became a different car, 2514. As long as it stayed in Italy, not a problem. But what happens?

when it crosses a border. Paperwork. So to make the paperwork match whatever the parts in the engine, it’s easier to fix because it’s all just paperwork, or [00:15:00] you put a little tiny metal strip over the actual number of the chassis, or the engine as the case may be. Everyone else says that’s 2512, but to the factory it’s 2514.

All their paperwork says 2514. All the automotive historians and people from tracking, you know, doing the chassis colt, checking all the blocks on that. It’s a different car. So that’s basically what Trev and I came to the conclusion. It’s like, There’s a problem here, and everyone thinks Trev and I were out of sync because they didn’t think, in this case, the Maserati.

But when Trev went back and started looking at the history of previous cars, we found the same thing. It wasn’t just the 250Fs, it was other cars prior to that. So what we’re basically saying is identity, as Trev, I think, made very clear, is not always what you think it is. So that’s one of the little things you have to watch when you’re a historian.

Particularly if you’re an automobile racing historian, it’s [00:16:00] sometimes what you’re given isn’t necessarily what the case is, it’s according to who you talk to. An automobile normally, as Trev correctly pointed out in the first slide, it has an identity as whatever the VIN number or the chassis number was.

But for the Italians, they thought a little differently. The motard was what they created. Did I do okay there, Trev? You’re doing fine. Now that you’re all confused, don’t laugh, we have fought this battle, Treveni, for what now, a better part of a decade? Something like that? Yeah, that’d be, uh, that would be close to it, and, uh, also, Don, uh, as you say, people saying to me that it cannot possibly be true.

Which is just a huge knee delight if you want me to prove something. I have a good friend who just got a Lifetime Achievement Award in England for his writings, this guy named Doug Nye. And Doug, you and I go back a long way. We’ve actually had Doug here at the Research Center. It’s 20 years ago now, but he is [00:17:00] reluctant to accept this because he’s a palmy and that’s how they do things.

It’s everything’s the chassis. But when I talk to people in Italy, they go, Sir Terzi, makes sense. A motori, motori. No, no, not an aereo. It’s a motori. So it’s a little different. And it’s just like anything else. When you switch over to certain types of history and nationalities, you have to be very careful.

We may all agree that on the auction block, it’s 25 12. But really? If it’s got the engine 2514 in it, that’s what the mechanics called it. So that’s really all Trev and I are saying. Give us a chance to do this. It’s not how everybody operates, but then again, I’m helpless. I do scientific notation. You give me a regular little calculator and I’m completely helpless because that’s how the mind works.

It is how they work. And I didn’t print off a copy, how the things, what about two centimeters thick now, three centimeters, four centimeters thick, the log book. [00:18:00] So there’s a lot of effort that goes into this. And we hope you get an understanding that identity, particularly in racing, is malleable, very malleable.

You could see Richard Petty in Car 43, but Car 43, one season is not Car 43 the next season, et cetera, et cetera. But it’s always want to you. Car 43. So that’s part of what got this going is it is changeable. It is malleable. Anyway, now that we confused you all, anything you want to throw in there, Trevor.

Thanks Don. As Don has said, the thing that we are working on tend to be much, much larger than just the 250S. The little internal recalibration that the engine will set the chassis numbers, the identity number for a particular race applies. Right across the board, picked it up in all sorts of places.

Every time we have a puzzle, we’ve managed to, uh, solve it by tracing and chasing the engine. Whether that be a sports car, Formula One car, or even a 1930s or a very early 1928s [00:19:00] comes down to the same thing. Engine equals identity, or at least for that day. Thanks, Don. That’s our story. And we are definitely sticking to it.

Okay. Any, any questions for us? Yeah, we got a couple. Last word. Don, I feel like the reason that Doug Nye doesn’t want to commit to accepting this research has nothing to do with his nationality and everything to do with the fact that Doug Nye is retained by auction companies to confirm the identity and history of valuable old racing cars.

And when yourself and Trevor. presented this research a couple of years ago at a conference that we were both at. I happened to have lunch with a very well known classic car and racing car broker. And I said to him, dude, what do you think of this? And he said, well, it’s all a load of bollocks because to try and unpick the identity of all of these cars, [00:20:00] it would destroy his credibility with.

People who he’s had business relationships with for years and years and years. So I’m not saying that it’s fine, that that’s the attitude. But what I am saying is that there’s a awful lot of money and an awful lot of water that’s gone under the bridge with a lot of these cars, and it would be very risky for his professional position for somebody like Doug Nye to say, you know what, all these Maserati 250Fs that we’ve identified as being, this is the Sterling Moss car, this is the Berra car.

We were suddenly to throw all of that up in the air and leave everybody feeling as faintly confused and dissatisfied as we’re feeling at the moment about the identity of these cars. There’s almost no upside. I feel it’s a little bit like when colleagues of mine at the university proposed. Systems to better identify whether or not a particular car was authentic or not.

Pushback that we had from within the old car community was, You know what? We don’t want to [00:21:00] know if it’s inauthentic. I want to believe that Stirling Moss owned my car and raced my car. It’s in nobody’s interest to do all of the research. Simply to cast doubt on the identity of this particular car. It was not an easy concept at first to accept because we’re all been drummed and this is how it is.

It was only those little pesky things called facts. And this was the key. If you dig and you dig, and that’s what we do. By dumb luck, I made acquaintance of a Hopkirk up in, uh, in British Columbia, Vancouver. Who had an interest in the 250Fs and was a maniac, basically. And he had all this chassis network that he created because some cars, you could count the louvers and some you could do the dents and all this sort of thing.

It was particular to that chassis. However, he also had gotten, by [00:22:00] accident, The numbers of the engines in those cars, and when I started noticing something that Barry just didn’t quite get, he thought I was nuts like everybody else. Was, wait a minute, you’re calling it 2512, but the factory’s calling it 2514, and everybody else is calling it because the chassis is 2512.

But the Italians are calling it that, so I’m, what’s wrong? But you’re correct, the commercial interest. And changing all this for, it, it would only be basically Maserati, Bondurant, Bondini, bunch of the Enies, if you will, that did this. Remember, Ferrari started off that way. And then because he had so many English customers, said it was much easier.

Because if you ever look at the Ferrari list, there is the Toleri, the, uh, Tolero, the, uh, chassis. But if the engine’s different, it’s noted. It’s always noted, and a lot of times you’ll find it in the paperwork, the Indran in the Ferrari paperwork. This is a fascinating topic. That [00:23:00] I never dreamed I’d ever be dealing with, but identity became an issue simply because it was so confusing.

I just want to say that I think it’s a little unfair to, uh, paint, uh, strictly Italian automakers for this kind of confusion, Doug and I, and I had a, a long and interesting session together on the identity of Lotus 19s. As most of us may know, a certain English manufacturer of a car’s name, Lotus, last name was Chapman.

Had a tendency to want to change things around and there were all sorts of good and sometimes bad reasons. Sometimes they needed to get it across the border. And the one that was on the paperwork had a fun chassis number. And the one they had in the truck was another one. So they changed it. In the case of Lotus 19s, it is truly murky.

I got involved with a car that claimed to be the first that Moss drove to two very successful races first at Riverside. And then at Monterey. There are three people in the world who claim [00:24:00] absolutely that they own that car. The joke is that the car was actually comprehensively destroyed in an accident in New Zealand, and the remains of the car came back in a suitcase that went into the baggage container of the jet that he came back on.

So it’s a fascinating topic and one that’s. Full of all sorts of problems. I’ve been yelled at any number of different times about that sort of thing. So good for you guys for doing it. It’s fascinating and the end. And also, of course, as we are hearing, it also relates a lot to not only value, but really what the history is and something that sometimes it’s just going to be too murky to dig out, but there it is.

It’s always boils down to one phrase, pity the poor historian. We can only do what we do. We do the facts. Again, Trev did a tremendous amount of work, and again, Trev and I go back a long ways on this, and we appreciate you giving us the patience to put up with it. Thank you so much for doing this, and I was curious if the logbook [00:25:00] extends to any of the French marks, specifically Delahaye is something I’ve been looking into, and I’m encountering some of the same issues.

There are others who have gone and replicated this, because one of the things we do as a historian, it’s different than, like, Doug, Doug keeps a lot of information. He holds it, which is what authors do, which historians do, until it gets published. I’ve thrown this information out there some time ago. I sat on a lot of information from Barry and another good friend of mine, David McKenzie, who did a lot of work, who helped unknowingly find the anomalies, because that’s what we look for.

We look for anomalies and helped me find some of these anomalies, even though he was not sure what I was looking for at first. There are a number of people come around to this. I think they basically still very quiet about it, exactly what John pointed out. Because then you start looking at Alfa Romeo, you start looking at these other companies as well, C.

I. A. T. So forth, a lot of them initially [00:26:00] did identity one way, but because of their customer base, they’re not stupid. They understand how the system works. And they found that out real quick. That don’t confuse people. All Trev and I do is confuse people. Because we look at the facts. And we don’t worry about the other stuff.

Thank goodness, because I would make a horrible car dealer. Tell you what it is, sort of thing. I just have a warning that none of this applies to American race cars up at least through 1980. Numbers per mil of cars have been lost. Frank Curtis and Watson. Numbered cars. And I have the bill sheets for most of the Offenheiser engines, but they changed engines without making any note at all.

An engine blew up, they put another one in and so what? Actually at one year in the fifties, there were more Offenheiser engines entered at Indy than had been built by Meyer and Drake at Offenheiser because people took blown up engines and bought some parts and put them together. So you can’t run the numbers.

You have to look at number of louvers and wells on [00:27:00] the chassis to identify them. And I should give some credit to Gordon because that was one of the anomalies that I began coming back to. I said, this can’t be unique. And you look at a lot of American racing cars, dirt track cars, etc. They didn’t have an identity except number 52, number 88.

That was basically it. And you’re right. When you had pointed out, said, you know, I’m not insane because Gordon has found the same thing on the, off the engines. And we said, we found that some of these engines, when they were broken, they got thrown. Chassis were, you know, like modern. There’s a couple of McLarens.

What? There must be like 15 of one chassis number because it wasn’t, it’s ridiculous. Identity is an open topic. Have at it as far as I’m concerned. Thank you very much. We appreciate it all. Thank you. Thank you, Don and Trevor. We could stay here till midnight, probably. Trevor sent me pages and pages of documentation, which he said pass along to whoever asks for it.

So I have a [00:28:00] PDF that’s, I don’t know, what, 30, 40 pages long, if you want it. And then you email me that you want it. It’s easy, easy as that. Okay, Trevor. Thank you much. Thank everybody in your team. Uh, right down to getting the invite to, uh, present to you guys. Okay. Appreciate it. Did it. And then thank you very much.

Just to finish on there, Bob. I have a friend who looked at what I’d done and he said. What are you worried about? He said that crawl over the John, Paul, George and Ringo would make no difference as long as you could track them, which I think it’s Donald’s point. There’s two different ways of tracking.

We’ll bring them together. So thank you. Thank you all very much. And, um, see you next time round. Thanks, Trevor. This episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center. Its charter is to collect, share, and preserve the history of motorsports, spanning continents, eras, and race series.

The center’s collection embodies the speed, drama, and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world. The Center welcomes serious researchers and casual fans alike to share [00:29:00] stories of race drivers, race series, and race cars captured on their shelves and walls and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events.

To learn more about the Center, visit www. racingarchives. org. This episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The SAH actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers. Organizational records, print ephemera and images to safeguard, as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding of motorized, wheeled land transportation through the modern age and into the future.

For more information about the SAH, visit www. autohistory. org.

We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Brake Fix Podcast brought to you by Gran Touring Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at GrandTouringMotorsports. And if you’d like [00:30:00] to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article at GTMotorsports.

org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as 2. 50 a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional Pit Stop minisodes, and other VIP goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators Fed on their strict diet of fig Newtons, gumby bears, and monster.

So consider signing up for Patreon today at www. patreon. com forward slash GT motorsports, and remember without you, none of this would be possible.

[00:31:00]