The following is an excerpt from the book, IMSA: 1969-1989, by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Porsche’s dominance during the 1974 season began to weigh on John Bishop. He understood the Camel GT Series was not sustainable if it became a one-marque show. And he worried about escalating costs if European manufacturers like Porsche and BMW controlled the supply of the most competitive cars. He wanted to find a way to bring American manufacturers to the front of the grid and offer a cost-effective, competitive product to private teams. But how? The answer came to him on an airplane.

“The old system favored limited production cars like Porsches and BMWs,” John later recounted. “There was no way high volume, cheaper production cars could compete with limited production cars with better components. They were simply better cars. What we needed was an American car that could compete with limited production sports cars from Europe. In the middle of the 1974 season, I was on my way somewhere on an airplane. It occurred to me that Porsche was abusing the FIA Group 5 rules with the turbo-powered 934 and then the 935 with its wilder bodywork. The Group 2 and 4 rules limited what you could do with the bodywork but not so with the Group 5 rules. There was total disregard for the future of the class. We couldn’t ban the Porsches. So, I figured we’ll just do what they’re doing.”

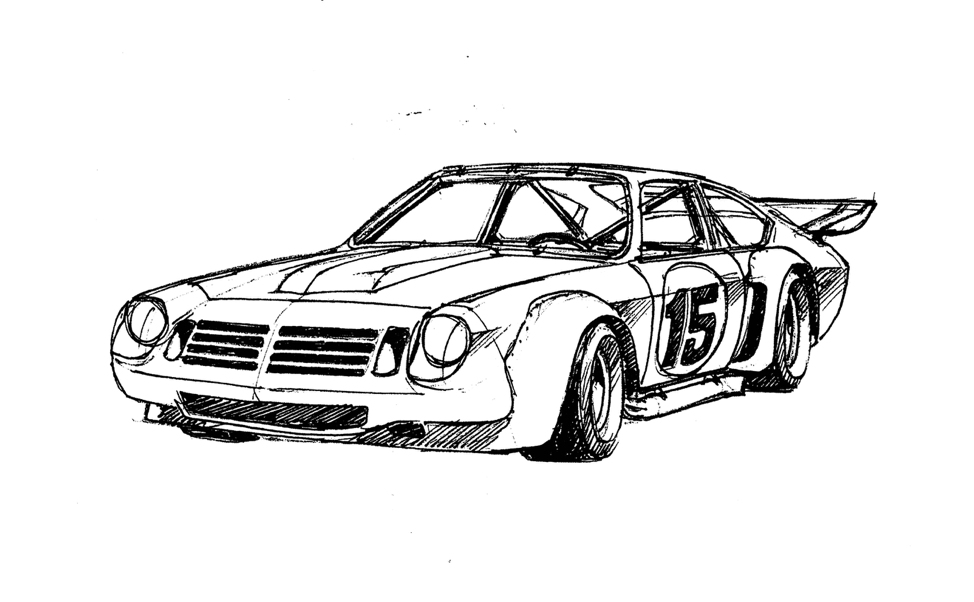

John Bishop’s original sketch of the All American GT concept he made on an airplane in 1974. This first concept drawing turned out to be very close to the first machines built for the AAGT class. Photo credit: Bishop Family

John Bishop’s original sketch of the All American GT concept he made on an airplane in 1974. This first concept drawing turned out to be very close to the first machines built for the AAGT class. Photo credit: Bishop Family

On the airplane, Bishop quickly sketched out his vision for American-based, tube-frame cars powered by readily available, low maintenance V8 engines, a class of cars that would be able to compete with the limited production, high-cost European Porsches and BMWs. He decided to call it All American GT (AAGT).

“The AAGT class was designed to allow tube-frame American cars to compete with limited production sports cars from Europe,” John recalled. “Porsche 935s were tube-frame cars at the end of the day. The only difference was that they rolled off a special production line in Germany, ready to race. The name AAGT came from our desire to give other people the same advantages that, by stretching the Group 5 rules, Porsche had enjoyed.”

Bishop started to share the AAGT concept in 1974 with some of the top competitors and at the end of the year IMSA published AAGT rules for the 1975 season. Steve Coleman and Amos Johnson debuted the very first AAGT car, a Chevy Vega they had built themselves, at the 1974 Daytona finale, where the car retired after managing just seven laps.

Steve Coleman and Amos Johnson’s home-built Chevrolet Vega, entered at the Daytona finale in November 1974, was the first AAGT in IMSA. Photo credit: ISC Archives & Research Center/Getty Image

“That was one of the overriding happiest reflections on IMSA,” remembered John later. “We could write a set of rules, talk about them with competitors, team owners and the like, publish the rules and then everybody would say; “Yes sir!” And they would go out there and spend money to build a car to those rules. We could create something great from just an idea.”

The new AAGT concept grabbed the attention of car builder and top engineer Lee Dykstra, who entered into a partnership with Horst Kwech in 1974 to form DeKon Engineering with the express purpose of designing, building and selling a competitive AAGT racer. With the direct assistance of Chevrolet, they began taking delivery of engines and other parts to construct the first wave of tube-frame Monzas. At just 2,400 pounds and powered by small-block V8s initially using Weber carburetors and later direct fuel injection, they produced 600 to 650bhp, making the Monzas balanced and lightning-fast. Purpose-built for racing, the only production parts appeared to be the roof and the windshield.

Kwech, already an accomplished racer, debuted the first production DeKon Monza at the Road Atlanta Camel GT doubleheader in April of 1975. He qualified fifth out of 40 cars entered, which got everyone’s attention, but retired after just 13 laps in the opening heat and didn’t start the second heat the next day due to teething issues. The bright spot was a privately built AAGT Monza driven by Tom Nehl, who finished eighth in both heats. The rest of the paddock began to see the potential of the new cars.

The first DeKon Monza campaigned in two races during the 1975 season. Australian Allan Moffat drove it at the Daytona 250-mile finale, on his way to a DNF after completing just fifteen laps. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com

DeKon Engineering continued to develop the car while another, privately-built version of the Monza arrived in the hands of Warren Agor, who finished a respectable 12th and 10th in the two heats at Lime Rock and scored another 10th at Mosport.

It was just a hint of things to come.

The AAGT concept gained speed with Porsche’s focus on the 934 and the Trans-Am for 1976. It put the top IMSA Porsche teams in a bind. Could they be competitive with the now-aging Carrera RSR against the BMW CSLs and new AAGT Monzas?

Al Holbert decided the answer was no. Although he had lobbied for the inclusion of the Porsche 934 for 1976, he preferred the larger rear wing, wider rear tires and lighter weight of the Monza compared to the RSR. Holbert purchased a DeKon Monza for the 1976 season and ran his first race at Road Atlanta in April with it after wisely sticking with the more reliable Porsche RSR for the longer Daytona and Sebring rounds. He finished second at the 24 hours of Daytona and won Sebring in March, co-driving with Michael Keyser, who then switched to the Monza.

By the Road Atlanta round in April, eight small block Monzas showed up from three constructors, including examples fielded by Keyser, Agor, Trueman, Nehl, Tom Frank and Jerry Jolly. There were many other AAGT cars as well: Coleman’s original AAGT Vega, five Greenwood- style Corvettes, Charlie Kemp’s wild Cobra II built by Bob Riley, and a host of Camaros led by the big orange No. 21 of Carl Shafer. Holbert and Keyser finished first and second in their DeKon Monzas, humiliating the rest of the field. The AAGT era had officially come of age.

Charlie Kemp’s wild AAGT Cobra II blowing smoke out the exhaust headers at Daytona. IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

Holbert went on to win four more races in the Monza to take the 1976 Camel GT championship. Keyser won two races with his version as well, cementing the future of American-built, tube-frame racers as the equal of anything produced on assembly lines in Europe. The Porsche Carrera RSR contingent included the usual faces along with George Dyer, Roberto Quintanilla, Bob Hagestad, John Gunn, John Graves, Monte Shelton, and others.

A host of Monzas head into the final turn at Laguna Seca during a heat race in 1977. Tom Frank leads Michael Keyser, Greg Pickett, Chris Cord, and Brad Frisselle, who took delivery of his car right before the race from Keyser and didn’t have time to apply graphics. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com

Al Holbert won a second consecutive Camel GT championship in 1977 in his potent AAGT Monza, updated with a larger rear wing, wider wheels, and more generous bodywork modifications that were allowed under new GTX rules. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com)

The AAGT revolution continued unabated for several years. Holbert won a second championship in a new winged Monza in 1977 against an onslaught of Porsche 934/5s. Other manufacturers became involved in the AAGT class, including Bob Sharp with the Datsun 280ZX twin-turbo V8. The bodywork, aero packages, and engines got so outrageous that IMSA dropped the AAGT moniker and changed the name of the class to GT eXperimental (GTX) in 1978. GTX became a combined class that included Group 5 Porsche 935s and all manner of AAGT machinery.

With rules changes that allowed for wilder bodywork, AAGT machinery continued to compete effectively with the Porsche 935 and the BMW turbo in 1978. Carl Shafer’s Camaro exits from under the bridge at Road Atlanta and starts the downhill plunge to the start/finish line. Photo credit: Bruce Czaja

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” written by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf that tells the inside story of how IMSA got started and its first 20 glorious years. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

______________________________________________________________________________

John Bishop’s early vision for sports car racing in the U.S. was influenced by the Federation Internationale de le’Automobile (FIA), the governing body for all international racing. But his decision in 1980 to create the IMSA GTP category that differed significantly from Group C regulations set down by the FIA the following year wasn’t an easy one. In the end, it resulted in a hugely popular class that would distinguish IMSA and racing in North America from the rest of the endurance racing world for more than a decade.

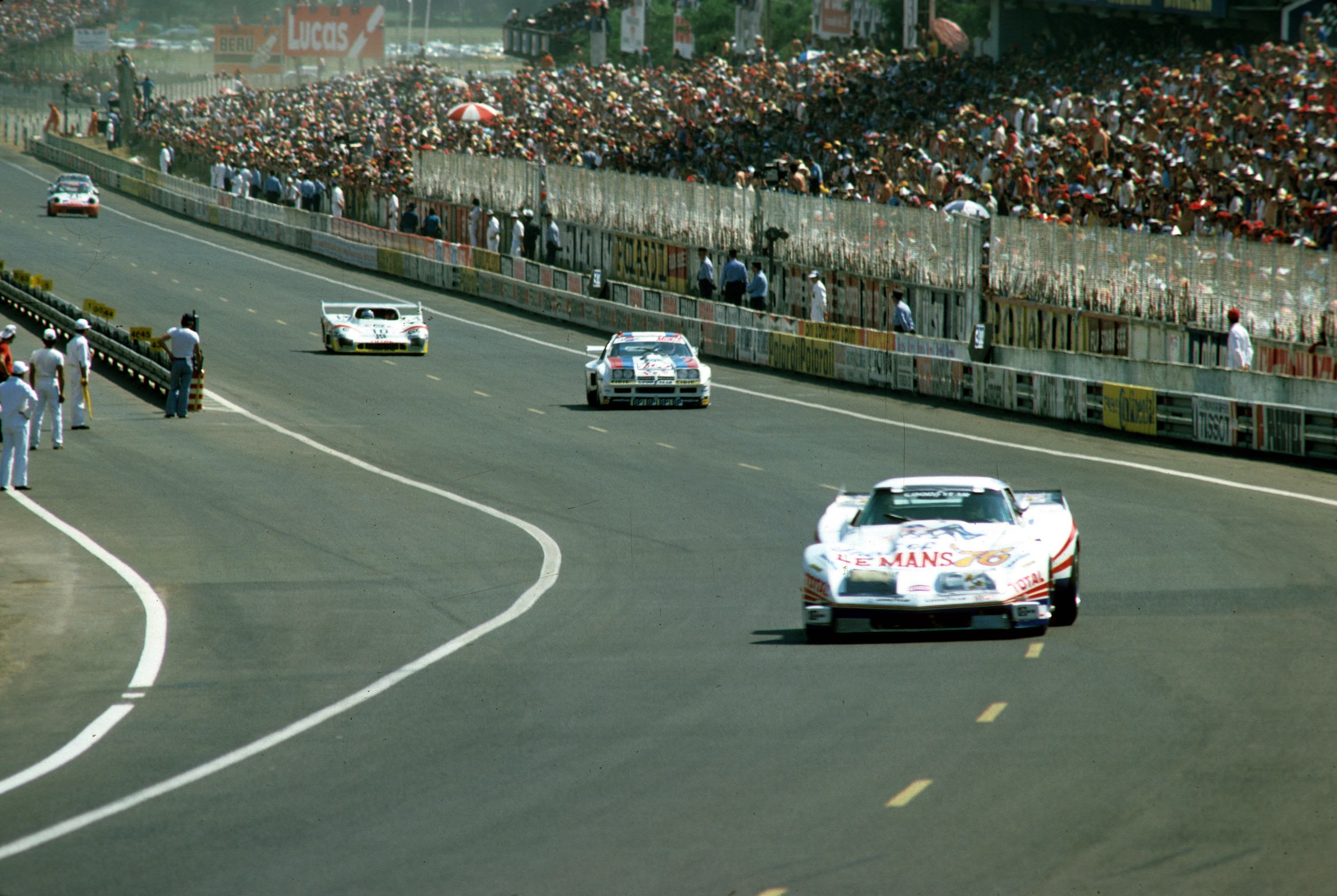

By the mid-1970s, the FIA class structure (Groups 1-6) for endurance racing was floundering in Europe, while IMSA’s race entries were growing. IMSA’s success did not go unnoticed by the FIA and the organizers of Le Mans, the most prestigious event on the international sportscar calendar. In 1976, an event partnership between Daytona International Speedway and the Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO), the Le Mans organizers, brought IMSA’s popular Corvettes and Monzas to the famed French 24-hour race, where they ran in a special class. John Greenwood’s Corvette and Michael Keyser’s Monza both ran strongly, even leading the Group 6 prototypes early in the race. Greenwood recorded the fastest top speeds on the Mulsanne straight that year, an astounding 215 mph. Although both cars were eventually forced to retire with mechanical woes, non-homologated American cars from IMSA were making a mockery of the FIA rules structure.

In the early laps of the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1976, John Greenwood’s Corvette leads Michael Keyser’s Monza and the eventual runner-up Group 6 Mirage Ford GR8. The IMSA class cars were popular with the fans and ran strongly before both dropped out with driveline/transmission problems. Photo: autosportsltd.com

The situation led to a new and productive relationship between Bishop and Alain Bertaut, the Director of Competition for the ACO. Both men shared similar values and appreciation for giving the private entrant a fighting chance. They also agreed that controls were needed to reign in the rapidly escalating costs of competition. But most importantly, they saw eye-to-eye on the importance of putting on a good show for paying spectators.

Bertaut, Bishop and Bill France Sr. began working together to encourage participation by the same teams and manufacturers in the 24-hour races at Daytona and Le Mans, including an invitation by the ACO for NASCAR stock cars to race at Le Mans in 1976, when NASCAR drivers Dick Brooks and Dick Hutcherson drove a Junie Donlavey-entered Ford Torino. Eventually, an entire class was devoted to IMSA at Le Mans due to the cars’ popularity with the European fans, a situation that lasted through the 1982 race.

The first turbocharged Porsche 934 ever to race anywhere in the world was at the 24 Hours of Daytona in January 1976, eligible only by special invitation to the World Championship of Makes Manufacturer championship. It finished forty-first, dropping out with mechanical issues. Photo: autosportsltd.com

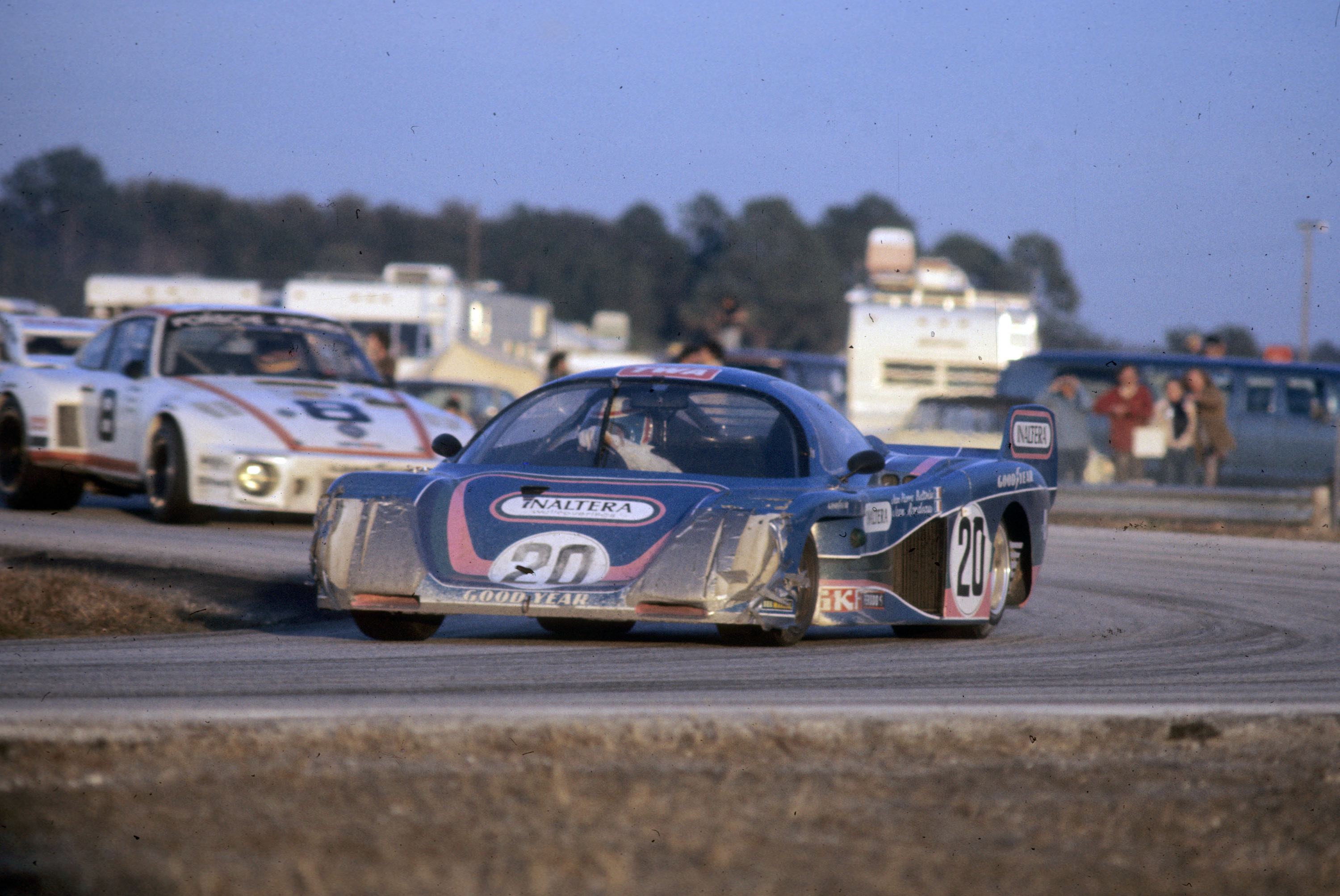

In a reciprocal arrangement, European-based cars were brought to the U.S. to race in the 24 Hours of Daytona, including the first Porsche 934 to race anywhere in the world in 1976, and the Inaltera built by Jean Rondeau that raced in 1977. The first Porsche 935s showed up at Daytona in 1977 as well, even though they were not yet eligible to compete in other Camel GT races. The Inaltera was entered in the “Le Mans GTP” class, a catch-all for cars that did not meet FIA Groups 1 through 6 regulations or anything else, and had been conceived by the ACO as a cost-effective alternative to Group 6. Over the years, the Le Mans GTP class included the WM-Peugeot, Rondeau 378 and the Porsche factory 924 Turbo GT cars.

The Martini & Rossi–sponsored factory Porsche 935 and a similar Kremer customer car were the first 935s to compete in an IMSA event, shown here on the front row of the grid at the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1977. Inaltera “Le Mans GTP” prototypes are on the second row. Both car types competed as part of the World Championship of Makes. Photo: ISC Archives & Research Center/Getty Image

The IMSA-ACO relationship continued to grow. IMSA representatives regularly attended the 24 Hours of Le Mans to build relationships and help the U.S. teams participating there. Dick Barbour, Paul Newman, and Rolf Stommelen driving a Garretson-prepared Porsche 935, almost won the race overall in 1979, driving an IMSA-class car. All the signs pointed to a flourishing relationship between IMSA and the ACO, with movement toward a uniform set of technical rules that would guide both sides of the Atlantic.

The relationship flourished to the point that Bertaut traveled cross country in the Bishop’s Newell Coach during the summer of 1980 and the following year his daughter interned at the IMSA headquarters. The ideas that resulted in IMSA’s GTP class were hatched on that long cross-country drive in the motorhome. The class was envisioned as a simple prototype car governed by a sliding power-to-weight formula that would be attractive to both manufacturers and private constructors. Jean Rondeau had shown the way by winning Le Mans in June of 1980 in a car designed and built entirely in his garage, fitted with a detuned Cosworth customer Formula One engine.

From Bishop’s point of view, Porsche and its 935 were dominating the 1979 and 1980 seasons and he knew that it would be difficult to continue growing the Camel GT Series unless something changed. Although the racing was close, he worried that no one would continue to pay to see a Porsche parade. The AAGT concept had diversified the fields for a while, but the cars were increasingly uncompetitive against the onslaught of 935s, even with more relaxed GTX rules that allowed for tube frames, wider wheels and essentially unlimited bodywork tweaks. BMW, Nissan, and Ford had all been represented in the GTX class during this time, but only as solo or two-car efforts; there were no customer cars. And the price for a new Porsche 935 was in excess of $200,000, a huge sum at the time. Privateers were getting priced out of the game.

“The bottom line is that private entrants fielding American-powered cars were never going to be able to keep up with the money invested by large manufacturers like Porsche, who were continually developing customer cars with virtually unlimited funds,” remembered Bishop. “We needed something new. We liked the general direction that the ACO and FIA were taking that allowed entrants to pair prototype monocoques with different engines, but somehow the Group C rules had become driven by fuel consumption as a result of the recent gas crisis. The Europeans seemed out of touch with what sold tickets in the U.S. We didn’t think fans wanted to watch high-powered racing cars coast by in an effort to save gas to make it the end of the race.”

“We were initially inspired by the Inaltera cars that showed up for the 1977 24 Hours of Daytona in a special prototype class,” Bishop continued. “The cars were fast, good looking and competitive. Best of all, they were built with off-the-shelf parts by Jean Rondeau, a private entrant, so we knew it could be done on a reasonable budget. Given the availability of a wide variety of reliable engines, our vision was to repeat a bit of the same formula that had made the AAGT class such a success. Our goal was to create a prototype class that could compete head-to-head with the 935s, but at a lower price point.”

One of two Inaltera “Le Mans GTP” class cars during the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1977. The privately designed and built machines became the inspiration for the IMSA GTP class rules developed in 1980. Photo: autosportsltd.com

After Rondeau’s victory at Le Mans in 1980, the IMSA-ACO relationship continued to gain steam. By contrast, the FIA’s World Championship of Makes continued to lose traction. Grids were small and participation by manufacturers sporadic. After much hand wringing, the FIA announced a response in 1980. It would abandon the Group 1 through 6 model and revamp all technical regulations into a new structure of Groups A, B, and C. Group A encompassed touring cars, Group B included GT cars along with limited production touring cars, and Group C defined sports prototypes.

There was one problem: IMSA had already publicly committed to the GTP concept as the alternative to the dominating Porsche 935. By the time of the FIA’s announcement on Group C, the GTP concept was well underway with chassis layout, engine options and a weight/displacement scale already decided on with mutual IMSA/ACO support. And manufacturers like Lola, BMW, and March were already building cars.

The hope was that all parties would embrace the IMSA GTP concept given that IMSA and the ACO were aligned and cars were already being built. However, the FIA went in another direction for its Group C class rules by insisting on a fuel consumption formula for the World Championship of Makes.

Without Le Mans on the World Championship of Makes calendar, it was doubtful whether the FIA series could survive. With an impasse looming over which rules would be used at Le Mans, the FIA, through its control of the World Championship of Makes, decided to play hardball. Jean-Marie Balestre was the president of the FISA – the sporting arm of the FIA – and also happened to be the president of the organization that controlled auto racing in France known as the Fédération Française du Sport Automobile. Wearing both hats, Balestre threatened to not to list the 24 Hours of Le Mans as an international event unless the ACO adopted the new Group C regulations along with the fuel consumption format. The ACO was forced into a corner, because not being listed would create licensing and legal havoc, among other problems. Although Bertaut was more philosophically aligned with IMSA, he had no real choice but to acquiesce to the political pressure in France. The ACO agreed to adopt the FIA Group C formula.

Although IMSA GTP and Group C cars turned out to be very similar, there were three critical technical differences that would keep them apart. IMSA required the driver’s feet to be behind the centerline of the front axle for safety reasons from the earliest time the rules were drawn up. Second, the fuel consumption formula favored smaller displacement, predominantly European racing engines that did not offer privateers, American or Japanese brands an equal opportunity to succeed without significant investment in new technologies. And finally, IMSA GTP rules required the use of production-based engines.

Due to these fundamental divides, IMSA went its own way. IMSA GTP chassis from Lola, March, Jaguar, and Ford appeared by 1983 and won the championships in 198 and 1983 through 1993. With the introduction of Group C in 1982 first at Silverstone and then at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the IMSA class subsequently fell away at the famed event. The Group C specifications did help the newly renamed World Endurance Championship of Makes regain its footing in Europe and became the World Sports-Prototype Championship in 1987. At the same time, IMSA grew and succeeded with the IMSA GTP concept in the U.S. Meanwhile, Japanese rule makers developed a similar, but unique style of prototype racing in Japan that didn’t exactly match either Group C or IMSA GTP.

By 1984, IMSA Camel GT fields were packed with GTP machines, as illustrated here at Michigan International Speedway. A Ford Mustang GTP leads from a few March chassis, two Jaguars, two newly introduced Porsche 962s and others. Photo: Bob Harmeyer

As a result, three separate prototype championships evolved that dominated their respective markets for over a decade. Ironically, this became the most successful period of global sports car racing in history. Manufacturers that participated in Group C included Lancia, Porsche, Mercedes, Ford, BMW, Nissan, Jaguar, Toyota, Mazda, Rondeau, Sauber, Spice, Lola, Argo, Tiga, and Alba, among others. A similar group or road car and racing car manufacturers participated in IMSA: Porsche, Jaguar, Nissan, Mazda, Ford, BMW, Toyota, Acura, Spice, Argo, Tiga, and Alba, in addition to U.S brands Chevrolet, Buick, and Pontiac. In Japan, Nissan, Toyota, Mazda, and Porsche all took part. Not all of these brands necessarily participated in each series at the same time, but the U.S. market drove the creation and development of more manufacturer GTP cars than either of the other two series.

The technical situation changed in the FIA after some frightening accidents in Europe. In 1985, the FIA finally adopted the IMSA rule concerning the placement of the driver’s feet behind the front axle centerline. With this change, a common chassis could then be used around the world in the European-based World Endurance Championship of Teams, the U.S.-based Camel GT Series, and the Japanese Sports Prototype Championship.

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” that tells the inside story of John Bishop’s life and how he created the world’s greatest sports car racing series. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

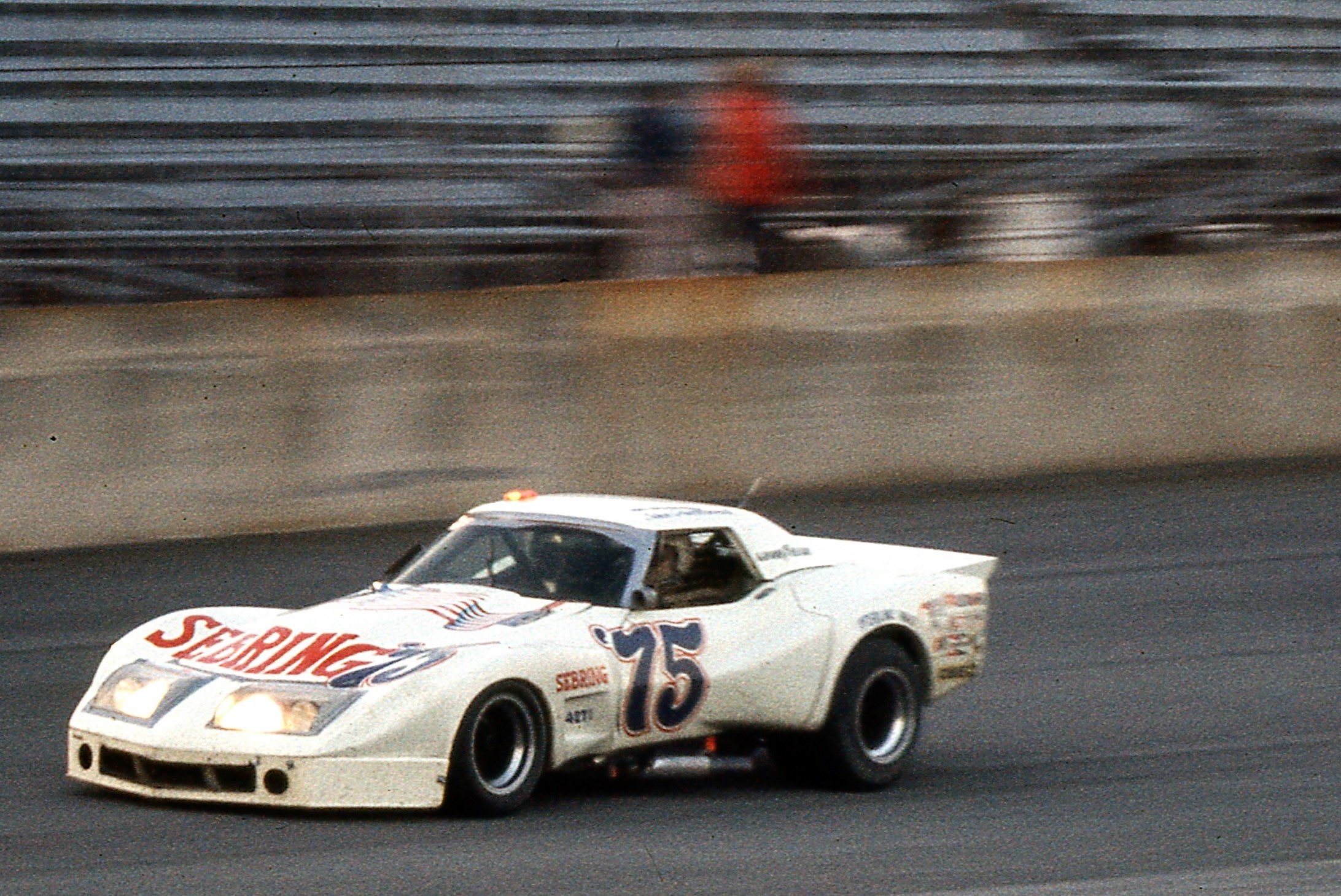

John Greenwood’s Corvette under braking for turn one during the 1975 24 Hours of Daytona, featuring his paint scheme promoting the 12 Hours of Sebring a few weeks later. Photo: Mark Raffauf

After a troublesome start at Daytona and subsequent upgrades to the car, the two-car factory BMW team showed up for the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1975 ready to mix it up. Australian touring car ace Alan Moffat supplemented the potent team of Hans Stuck, Sam Posey, Brian Redman, and Ronnie Peterson. The CSLs were now much improved and took advantage of specially crafted Dunlop tires. The old 5.2-mile Sebring course was a wide-open, hang-on-and-get-after-it circuit, where turns one and two were big, sweeping curves of concrete runway that required tremendous skill to navigate quickly without going off and hitting anything, including parked airplanes.

GT cars make their way down the massive back straight at Sebring in 1975. The runways of Sebring weren’t always as well marked as they are today. Nighttime navigation of the track was especially challenging. Photo: Mark Raffauf

In spite of John Greenwood’s Corvette taking pole, the BMWs stormed into an early lead. Within the first hour, Hans Stuck’s BMW was reported numerous times by corner workers at various locations not to have working brake lights. IMSA black-flagged the car to have its lights checked. Once in the pits, it was determined the lights were indeed working. A short time later the same reports started coming in: no brake lights, especially in turns one and two. The car was brought back in for another check. Again, all was good while stationary in the pits.

The winning factory BMW CSL of Hans Stuck, Sam Posey, Brian Redman, and Allan Moffat navigates the wide-open runways of Sebring in 1975 when Lockheed Constellations and Douglas DC-4s lined the course unprotected between turns one and two. Photo: Mark Raffauf

When the issue arose a third time, BMW team chief Jochen Neerpasch asked IMSA officials, “Where are the lights not working?” to which race control replied, “Various locations, including turns one and two.” Neerpasch responded with, “Oh, Hans does not use the brakes there at all!” With the stickier tires and improved performance, GT cars were now able to take turns one and two flat, or at least with a slight lift instead of braking. No one had ever seen that before, hence the confusion from the corner workers and race control.

The winners of the 1975 12 Hours of Sebring celebrate in Victory Lane. Sam Posey stands on top of the BMW CSL, flanked by Brian Redman (far right), Hans Stuck (seated next to Redman) and Allan Moffat (with daughter). Photo: Bill Oursler/autosportsltd.com

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” that tells the inside story of John Bishop’s life and how he created the world’s greatest sports car racing series. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

To many people, John Bishop became a savior in 1973. For twenty uninterrupted years, starting in 1952, the Sebring 12 Hour sports car endurance race for was held under the guidance of Alec Ulmann, one of the first members of the SCCA when it was founded in 1944. In 1950, Ulmann traveled to Le Mans to take in the sights and sounds of the 24-hour race. The experience inspired him to bring sports car endurance racing to the U.S., which he did with a six-hour race at Sebring later that year – the first such event held in America.

The Sebring track itself began life as Hendricks Army Airfield, a hastily built airport used during WWII as a training site for B-17 bomber crews. After the base was decommissioned in 1945, the airport was turned over to the local community. In the ensuing years, Ulmann convinced the airport authority to let him promote a series of races using the long runways and network of access roads as the track layout. As part of the agreement, one active runway remained in operation during the race.

The start of the first 12 Hours of Sebring in 1952. The event was the brainchild of Alec Ulmann, who organized the race on the decommissioned runways of a World War II B-17 training base. Photo: Sebring International Raceway Archives

Starting with the first 12 Hours of Sebring race in 1952, the event became a crown jewel on the international racing calendar, attracting the best and brightest drivers, manufacturers and race teams from around the world. The AAA acted as the sanctioning body for the first few years, until the organization quit the racing business after the now infamous Le Mans accident in 1955 that killed more than 80 spectators. After that, Alec and Mary Ulmann formed the Automobile Racing Club of Florida (ARCF) as an entity to produce and promote the race. Alec Ulmann was the vice president of the ARCF and also acted as race secretary for the event. The SCCA sanctioned the race from 1963 through 1972, with full backing from ACCUS and the FIA.

Nothing lasts forever, however. Years of use left the track surface broken, with large chunks of concrete regularly coming loose during events. The facilities were spartan for both competitors and spectators alike. Under pressure from the FIA to improve track safety for the ever-increasing speeds of new generation racing machines and to invest in better facilities for the growing crowds, the Ulmann family announced the 1972 running of the event would be the last. After 20 uninterrupted years, the Ulmann’s were tired and wanted to move on. Sebring appeared destined to become just another dusty footnote in racing history.

Recognizing an opportunity for IMSA to take over one of the world’s most recognized sports car events, Bishop approached Bill France Sr., the founder of NASCAR and investor in IMSA, with an idea for NASCAR to put up the money to save the Sebring race. France Sr. wasn’t convinced. According to Bishop: “Big Bill never understood why anyone would pay to see an event at Sebring, whose facilities, let’s say, fell far short of those at Daytona and Talladega.” Bishop couldn’t get his friend and partner to budge.

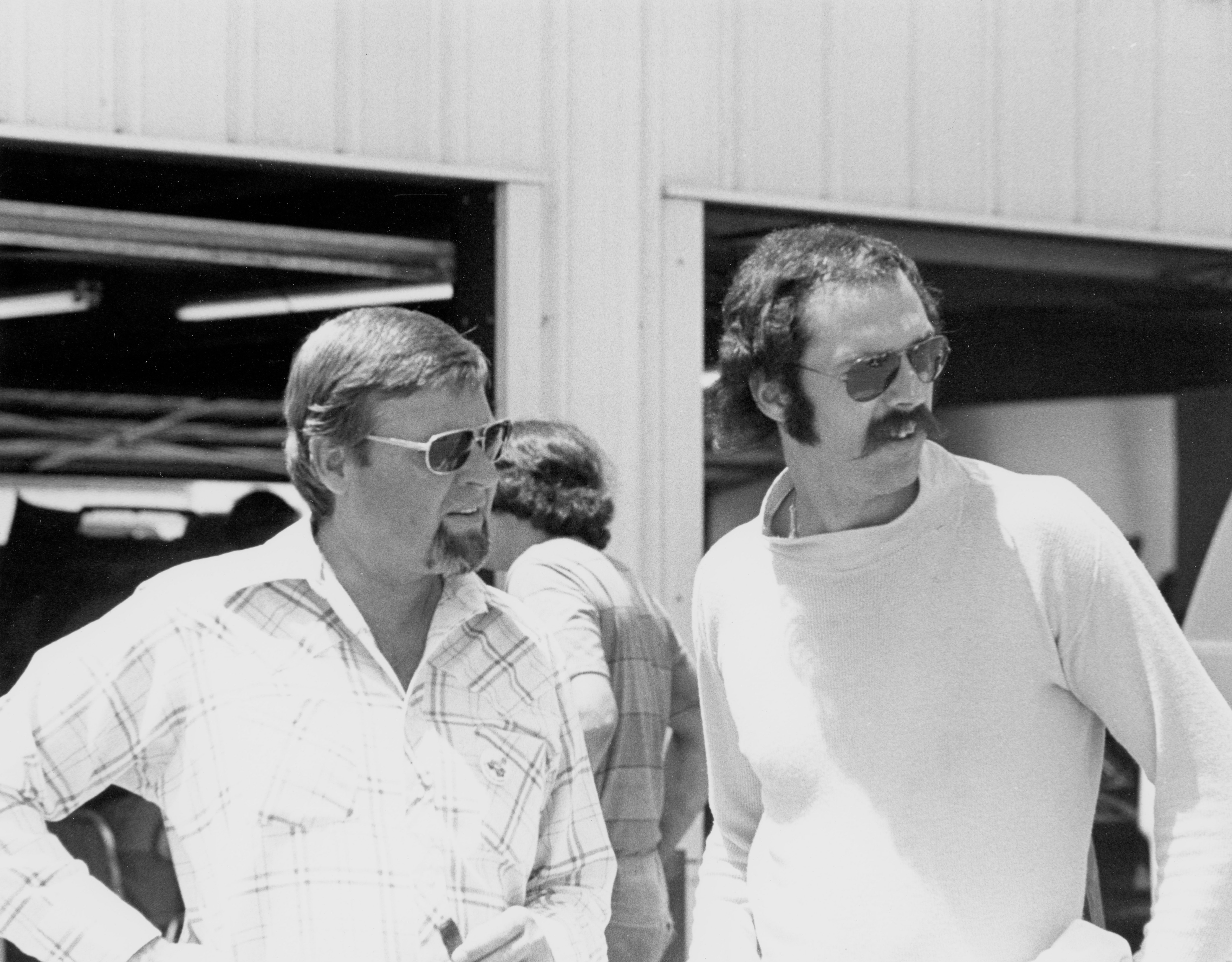

John Greenwood, on the right with Milt Minter, stepped up to bankroll the 1973 Sebring race, effectively saving the event. He would continue to be involved as a Sebring benefactor for years. IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

Then, providence intervened. Bishop happened to be talking with John Greenwood about Sebring on the pit wall at Daytona in January of 1973 and to his surprise, Greenwood offered to put up the money to save the event, including making some needed safety improvements to the track like building a higher wall separating the pits from the main straight. With only a few short weeks to get it all organized and done, the pressure and the stakes were high. But Bishop recognized an enormous opportunity to elevate IMSA’s status in the racing world.

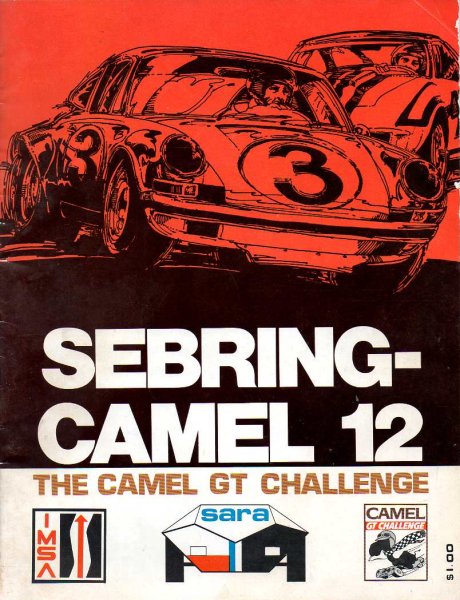

The program cover for the first IMSA-sanctioned 12 Hours of Sebring in 1973. Sebring International Raceway Archives

Reggie Smith, the ex-secretary of the ARCF, now the ex-promoter of the Sebring race, started a new organization called the Sebring Automobile Racing Association, which later on affectionately became known as the Sebring City Fathers. SARA became the official promoter of the event. Greenwood put up the prize money and made safety improvements to the track. R.J. Reynolds was more than happy to have Sebring added to the Camel GT Series calendar, which was now in its second year.

IMSA was not yet a member of ACCUS, which turned out to be a good thing, as it was not under any pressure to adhere to FIA edicts or existing ACCUS rules preventing drivers from crossing over from one member’s sanctioned race to compete in another. For unknown reasons, the SCCA board of governors voted not to interfere with IMSA taking over the race. The Club appeared to have given up on Sebring. All of this meant IMSA had a free hand to sanction an event with an almost mystical international reputation and attract drivers from any race-sanctioning body on the planet.

The runways, taxiways and access roads at Sebring have always been a challenge for racers. The Camaro shared by Luis Sereix, Tony Lilly, and Dave Voder navigates the rough pavement. Note the orange cones intended to guide the competitors at night when Sebring was pitch black and especially tricky to navigate. autosportsltd.com

The 12 Hours of Sebring became the first IMSA Camel GT event of the 1973 season. With the help of RJR’s Joe Camel advertising campaign and renewed interest in the race, a good crowd showed up, ensuring Sebring would become a fixture on the IMSA calendar for many years to come. For many people who lived through the near-extinction of the Sebring race, Bishop was recognized as one of three heroes who stepped in at the last minute to rescue this iconic event. In recognition of their contributions, Bishop, Greenwood and Smith were later inducted into the Sebring Hall of Fame.

The winning Porsche Carrera RS of Peter Gregg, Hurley Haywood, and Dave Helmick at Sebring in 1973. The traditional colors of Brumos were not used as it was Dave Helmick’s car. autosportsltd.com

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” that tells the inside story of John Bishop’s life and how he created the world’s greatest sports car racing series. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

Former IMSA RS and GTU champion Don Devendorf (right) was the leader behind Electramotive Engineering, the team that fielded the all-conquering Nissan GTP ZX-T in the IMSA Camel GT Series in the last half of the 1980s. The team won the IMSA championship in 1988 and 1989. Photo: Peter Gloede

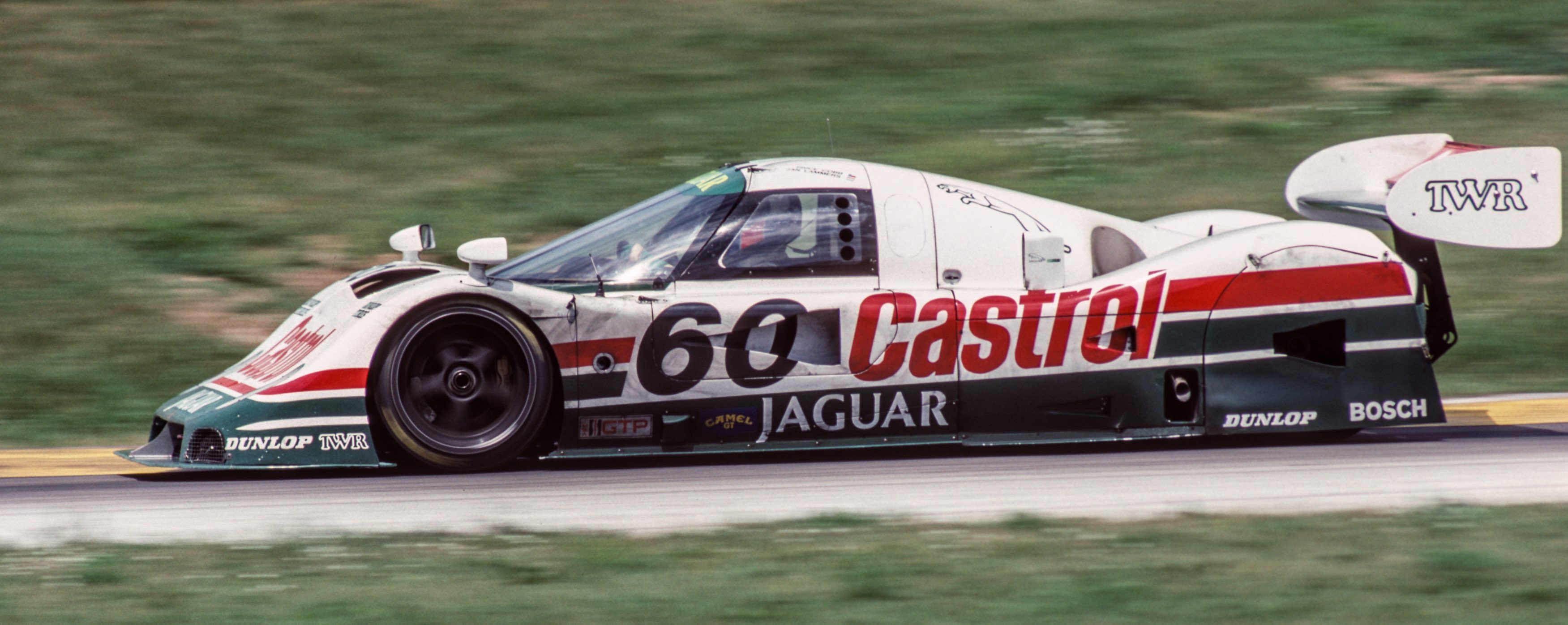

The TWR Racing Jaguar XJR-10 of Jan Lammers and Price Cobb led most of the way at Portland in 1989. Photo: Peter Gloede.

At the 1989 Portland round of the Camel GT Series, a titanic battle between the Nissans of Geoff Brabham and Chip Robinson and the two Castrol Walkinshaw Jaguars driven by Price Cobb/Jan Lammers and Davy Jones/John Nielsen lasted the entire distance. At the end of the race, an extraordinary sequence of events unfolded that created confusion and a tough decision for IMSA officials.

Jaguar ran two different cars in 1989—the XJR-9 (foreground) that featured a 7.0-liter, 12-cylinder, normally aspirated engine, and the new XJR-10 designed around a 3.0-liter, 6-cylinder twin-turbocharged motor. The cars are shown here at the previous round at Road America, sitting next to the Castrol transporter. Photo: Peter Gloede

Although the race was scheduled for 102 laps, for reasons never fully understood the local SCCA starter took it upon himself to throw the checkered flag on the 94th lap instead. About a third of the field took that flag, including the leaders – Cobb over Brabham by little more than one second. The teams knew the race was supposed to go 102 laps, so, for the most part, they told their drivers to keep right on racing. After a few cars took the checkered flag, IMSA race control realized what had happened, so they told the starter to pull in the checkered flag. The remaining cars flew by as if nothing had happened.

The Electramotive team was well known for their lightning-quick pit stops during their championship years, pictured here at Road America in 1989. Photo: Peter Gloede

Race control notified everyone on the radio that the race was proceeding to the full race distance. Five laps later, Brabham got by Cobb and took the second checkered flag after 102 laps. In the meantime, IMSA officials consulted the regulations and came to the decision that although the first checkered flag was flown early, it had to signify the end of the race: the event was over as of 94 laps and the win was awarded to Cobb/Lammers based on the standings at that time.

The now incensed Nissan team protested the results, which were held as provisional until the appeal could be heard by well-respected former driver John Gordon Bennett, IMSA’s commissioner. Bennett was the highest level of independent decision-making in IMSA’s appeal process. In other words, his decision would be final.

Realizing the intricacies of the situation, Bennett convened a panel of three other experts unaffiliated in any way with the parties in the dispute. The panel concluded that although incorrectly displayed, the sanctity of the checkered flag could not be disputed. IMSA was chastised by the panel for allowing the unfortunate flagging error to happen. The organization never again depended on local starters at races, instead bringing its own starter to every event. The Nissan team was disappointed, but the decision was accepted after one more minor protest.

At the next race in San Antonio, Nissan handed out a wonderfully designed lapel pin showing the number 83 car, a checkered flag, the words “Portland 1989” and a large screw going through the car, illustrating their feelings about what had happened in the Pacific Northwest.

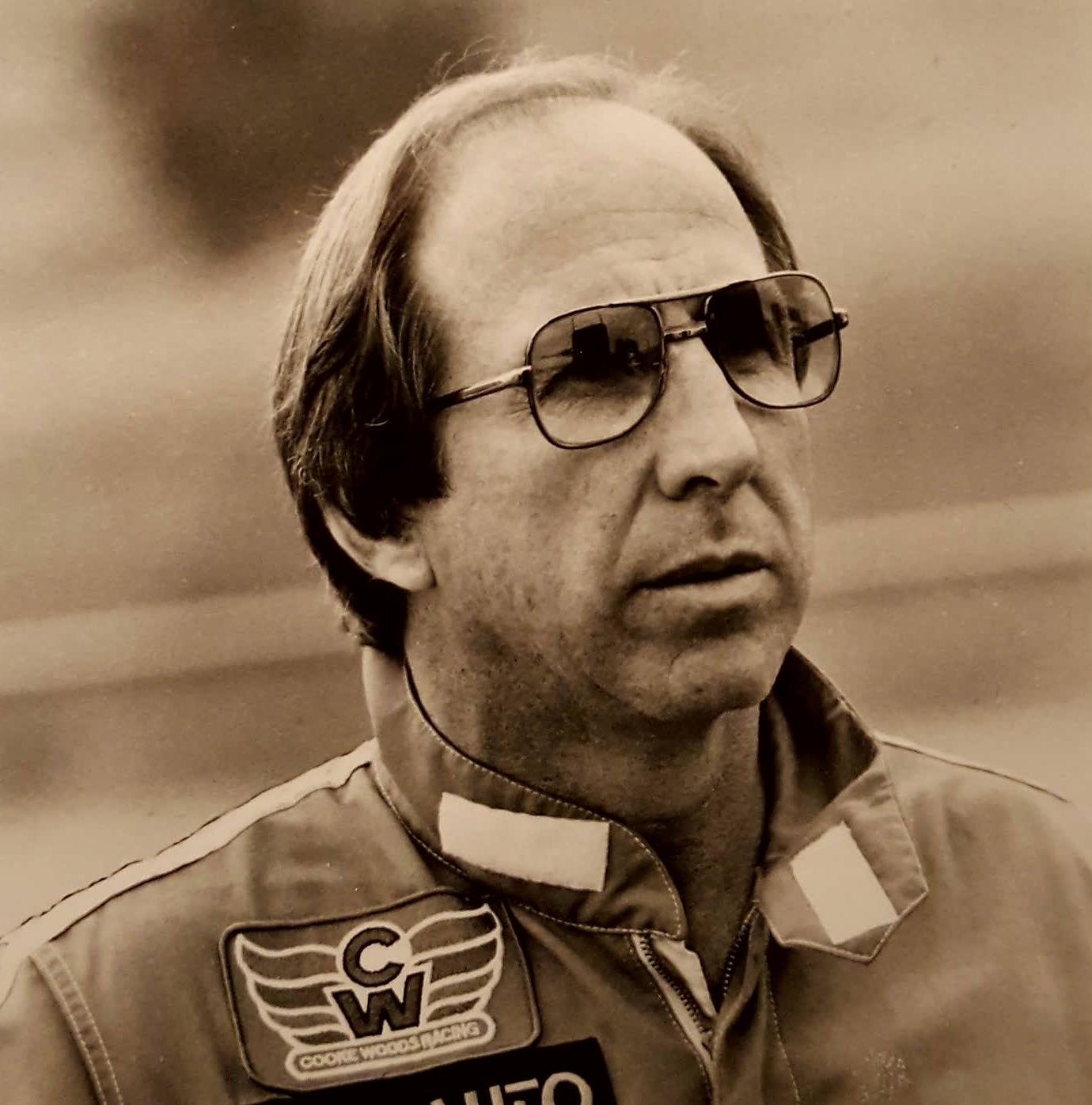

The 1981 24 Hours of Daytona shaped up to be another battle of Porsche 935s. The 935 had won the last three Daytona endurance races in a row starting in 1978. Although the 935 was based on a street 930, it was fast and reliable when properly prepared. Dick Barbour, after winning the IMSA championship with driver John Fitzpatrick in 1980, had stopped racing. That gave Bob Garretson the opportunity to continue with the same crew on his car in 1981 – a Porsche 935 (chassis 009 0030) which the team had built from a bare factory chassis in 1979. Bob had signed a new deal for 1981 to prepare the Cooke-Woods cars. This was a partnership between Roy Woods and Ralph Cooke. New Lola T600s had been ordered but would not be ready until later in the year, so the Porsche 935 would be run in the meantime. In any case, the Porsche would be more reliable for the 24 Hours of Daytona.

Team principal Bob Garretson just prior to the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1981.

The car would be driven at Daytona by Bob, Brian Redman, and Bobby Rahal. We seemed to struggle a bit in getting everything ready and prepared up to our normal standards. We were still putting the car together at the track, missing a few practice sessions. We had to send Brian Redman out to qualify using the session as a brake pad bedding session, so we ended up only 16th on the grid. Brian, however, was happy with the car and told us not to worry, all was well for the race.

The race featured no less than 15 or so Porsche 935s or derivatives, as well as the factory Lancia team, running the 2.0-liter MonteCarlos in the World Championship. At the green flag most took off at high speed, pushing like it was a one-hour sprint race. It wasn’t long before engines were blowing up left and right. Many of these cars came into the pits to change engines, which was legal back then. Several went through two engines.

One of the 2.0-liter turbocharged factory Lancia Betas that ran against an onslaught of Porsche 935s in the 1981 Daytona endurance classic. This one was driven by Formula One standout Ricardo Patrese, along with Hans Heyer and Henri Pescarolo. They would finish 18th. Photo: Martin Raffauf

In contrast, we ran to our pace and soon were running at the front from the 16th starting position. At one driver change in the early evening, Brian was furious with Bobby Rahal, as he had taken the lead during his stint; Brian told Bobby he was pushing too hard! Bobby was apologetic and said, “I didn’t pass anyone, they are all falling out.” Brian wandered off muttering, “It’s too early, it’s too early.”

The Garretson Porsche 935 on the tri-oval during practice for the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1981. Photo: Martin Raffauf

Around midnight, the Interscope 935 crashed with a backmarker and our car ran over some debris from the incident, which broke an exhaust pipe. This was quickly changed in the ensuing pit stop. By Sunday morning we were cruising and had a large lead of some 10-15 laps. Brian came in at about 6:45 am after a double stint, handed over to Bobby and asked, “Where’s breakfast?” Well, we said, nothing has been organized on that front yet. “Ok, he said, I’ll take care of it.” I remember thinking, how is he going to get breakfast? About 20 minutes later, Brian came back to the pits with bags of McDonald’s breakfast sandwiches. He had driven across the street to the McDonalds across from the speedway, still in his driving uniform, picked up food for the crew and had brought it back to the pits. He sat and ate with the mechanics in the pit, then went off to prepare for his next stint.

One of the friends of the team at this time, who was in our pit a lot, was Olivier Chandon, son of the French champagne house. By early Sunday, he began to get concerned, as he thought we would win, and there was crappy champagne on hand from the speedway for the Victory Lane celebration (in his view). The crew, of course, were not interested in any of this and ignored him, as we knew it was not “over until it’s over” as Yogi Berra used to say. We were just focused on making it to the end, not worrying about what kind of champagne we would drink, if any! In any case, Olivier was calling all over Daytona looking for Moet & Chandon but none was to be found. So, bless his soul, he jumped in a rental car, drove to Orlando, found the right stuff, and sped back to the circuit with the Moet & Chandon by noon or so.

The Garretson crew rushes towards the finish line to salute their car as it wins the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1981. That’s the author on the far right in the blue overalls, raising his red hat in celebration. Race organizers were not pleased with this behavior and outlawed such displays in the future due to safety concerns. Photo: Peter Gloede

We ran off the remaining laps without issue and won the race. An Egg McMuffin paired with Moet & Chandon; does it get any better? It was a grand celebration and Olivier was happy he could provide “the proper champagne!” Sadly, Olivier lost his life a few years later in a Formula Atlantic crash at West Palm Beach. But we always remember and salute the Moet & Chandon!

Victory Lane celebrations were sweet in 1981 with the right champagne! Photo: Peter Gloede

The following is an excerpt from the book “IMSA 1969-1989” written by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf, available from Octane Press or where ever books are sold.

The race-winning ANDIAL-powered, tube-frame Porsche 935 with full “Moby Dick” Le Mans bodywork at the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1983. The team of Wollek, Ballot-Lena, Foyt and Henn would go on to win the race. Photo: Bob Harmeyer

At the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1983, the Aston Martin brand was represented by two Nimrod V8 cars, one driven by A.J. Foyt and Darrell Waltrip and painted in Pepsi Challenger colors. On the pole was the ANDIAL tube frame 935, now converted to full “Moby Dick” long tail bodywork specially made for Le Mans. It was the monster of all 935s – the new body was on the same chassis that Rolf Stommelen had driven to the three straight long-distance victories in 1981. European veterans Bob Wollek and Claude Ballot-Lena were entered to co-drive with car owner and T-Bird Swap Shop entrepreneur Preston Henn.

Early on in the 1983 24 Hours of Daytona, the Swap Shop Porsche 935 leads the Pepsi-sponsored Aston Martin Nimrod GTP shared by A.J. Foyt and Darrell Waltrip. The Nimrod would drop out after 121 laps. Photo: Peter Gloede

Early retirements by JLP, Interscope, Bob Akin Racing and others kept the Swap Shop Porsche in close contact with first place through the first half of the race. After Foyt’s Nimrod also retired, Henn asked A.J. if he wanted to drive his car since it had a chance to win. Foyt agreed and got ready to climb in early Sunday morning at the beginning of what turned out to be an extended full course caution caused by heavy rain. The problem? Henn didn’t tell the other drivers.

Rain delayed the 1983 24 Hours of Daytona with a lengthy caution period and a red flag situation on Sunday morning. Photo: Bob Harmeyer

When Wollek pulled into the pits and opened the door to climb out, he saw Foyt on the pit wall dressed for battle and instantly realized what was about to transpire. Upset by Foyt taking over the car with a lead he had established and fearful the Texan would ruin the team’s race, Wollek tried to close the door and drive off. But the team physically pulled him from the car. Wollek was disgusted. He had put the car at the front and believed Henn was throwing the race away because Foyt had never driven the car before – nor driven at Daytona in the wet. But Foyt used a nearly two-hour full course caution period to learn the car and when the race was finally restarted, took off in the lead. Once again, Foyt affirmed his status as one of the all-time greats. The team went on to win the race.

Bob Wollek watches as A.J. Foyt climbs into the Swap Shop Porsche 935 early Sunday morning. Wollek’s body language tells a story in itself. Note the heavy media interest. Photo: Peter Gloede

All was forgiven in Victory Lane, but Wollek was still a bit perturbed with the whole episode. Reportedly Foyt turned to Wollek after the race and asked him; “How many times have you been to Le Mans?” Wollek answered; “At least a dozen times!” Foyt retorted: “How many times have you won?” Wollek, of course, had not won Le Mans. Foyt reminded him; “I’ve been to Le Mans once, and won.” They eventually became good friends and team mates, driving to victory together at Daytona and Sebring two years later in a Porsche 962.

The following is an excerpt from the book “IMSA 1969-1989” written by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf, available from Octane Press or where ever books are sold.

The 1976 24 Hours of Daytona was possibly the most unusual Camel GT race ever run. A record 72 entries showed up and the event had a relatively normal first 15 hours. After racing through the night, the BMW CSL of Peter Gregg and Brian Redman held an enormous 17-lap lead as the sun came up Sunday morning. But when Redman stopped for fuel and tires just after 9:00 a.m., the car misfired and then stalled coming out of the pits. Stranded out on the course, Redman tried to get the car re-fired, to no avail. He eventually borrowed jumper cables and a battery from some helpful fans beside the track and somehow managed to coax the BMW back to life and limped back to the pits. In the meantime, nine of the top ten cars in the race began to suffer the same symptoms, they were coughing and coming to a halt after refueling. The culprit? Water in the gasoline.

Brian Redman’s stricken BMW CSL during the 1976 24 Hours of Daytona, after stalling out on course with water tainted gasoline. Redman is trying to get it restarted with coaching from his crew, who were not allowed to touch the car. Photo credit: ISC Archives & Research Center/Getty Image

The decision was made to red flag the race an hour after the problems first started appearing; IMSA wanted to avoid having the entire field suffer the same fate. After some investigation, it was determined that the affected teams had all been serviced by a single gasoline truck. Somehow, water had been introduced into the fuel carried by that one truck.

John Bishop conferred with Chief Steward Charlie Rainville and the decision was made to roll back timing and scoring to the last complete lap before the problem first emerged at 9:01 a.m. on Sunday morning. That call was cheered by some teams and derided by others, depending on whether their car had been felled by the bad fuel or not.

As John later recalled: “Rolling back scoring of the race seemed like the only fair thing to do. Some of the teams that had dodged the bad fuel issue were upset, but you have to remember that this was an extraordinary, unprecedented situation that was out of the control of even the most well-prepared teams or the track.”

By the time a replacement truck with fuel arrived from Jacksonville, 90 miles away, two and a half hours had elapsed. Normally, teams were not allowed to work on their cars under red flag conditions, but in this case, IMSA officials told everyone they could use the time to purge their fuel systems to get running again. Those with foam-filled fuel cells were doomed, however, because the water had been absorbed into the lining of the cell.

The BMW teams are serviced in the pit lane at Daytona in 1976 after the 24 hour race was red flagged. Teams were allowed to work on their cars to purge their fuel tanks, which had become contaminated with water. Red and green barrels were used to indicate which contained “good” and “bad” fuel. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com

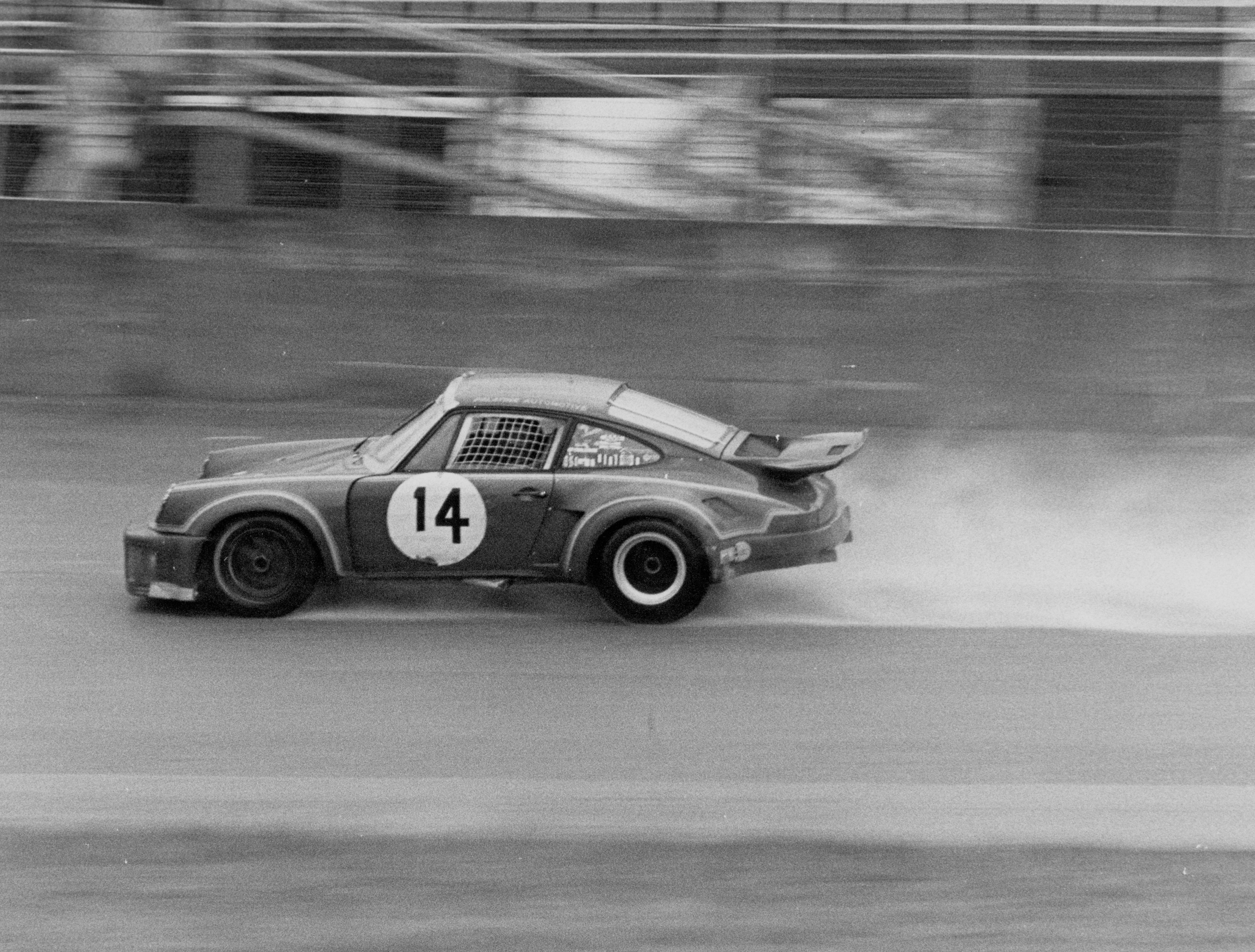

The #14 Al Holbert/Claude Ballot-Lena Porsche Carrera RSR is serviced during the lengthy red flag due to water contaminated gasoline during the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1976. The pair would go on to finish second in the race. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com

Once their fuel system had been cleaned, Redman and Gregg resumed the race with their 17-lap lead intact, almost three hours after the race had been red flagged and almost four hours since the last officially scored lap. Just 29 cars restarted the race, the rest having fallen out prior to the fuel issue or having been done in by the tainted gasoline. The duo of Redman and Gregg went on to win by 14 laps over Al Holbert and Claude Ballot-Lena in a Carrera RSR. It would be the third 24 Hours of Daytona victory for Gregg.

The winning BMW CSL of Brian Redman and Peter Gregg at the 1976 24 Hours of Daytona. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com

The second place Porsche Carrera RSR of Al Holbert and Claude Ballot-Lena flies through the tri-oval in the rain at the 1976 24 Hours of Daytona. Photo credit: International Motor Racing Research Center/IMSA Collection