The 20-year struggle by Dr. Robert Hubbard and Jim Downing to gain universal acceptance for their life-saving HANS Device—now in use by over 275,000 competitors worldwide—is an amazing tale of family, genius, perseverance, tragedy and triumph. It tells how the world’s leading auto racing series shouldered the task of saving their driving heroes—and a sport. Excerpted from the book CRASH! by Jonathan Ingram (with Dr. Robert Hubbard and Jim Downing), this is the story of Jim Downing’s awakening to the very real dangers of high-speed frontal impacts and his resolve to do something about it. The full book can be purchased here.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Chapter 2. Downing’s Awakening

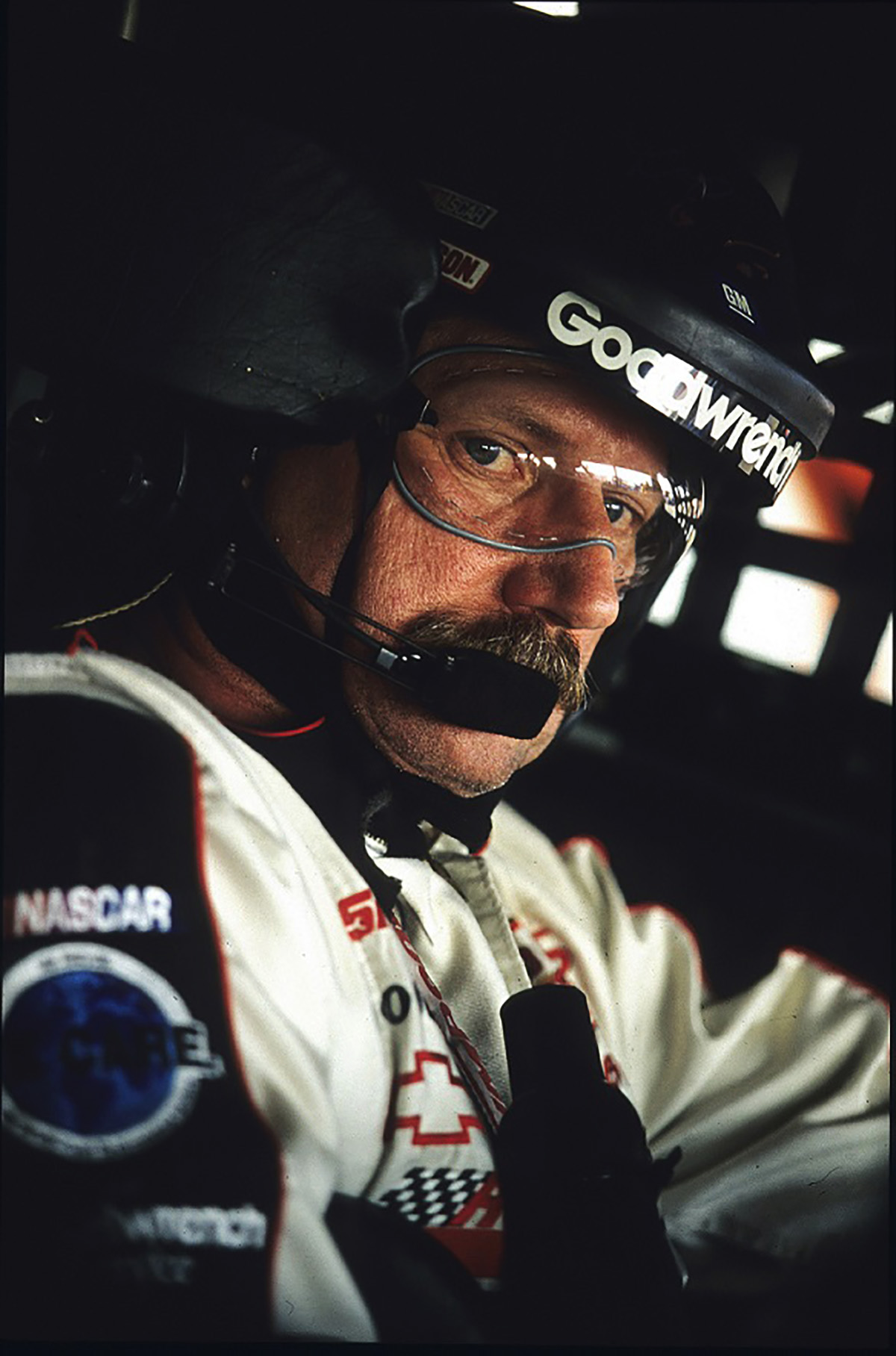

A five-time road racing champion, Jim Downing first met Dale Earnhardt in the NASCAR hauler at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 2000, where he was talking about the HANS Device to a longtime acquaintance, Mike Helton, soon to be named the NASCAR president.

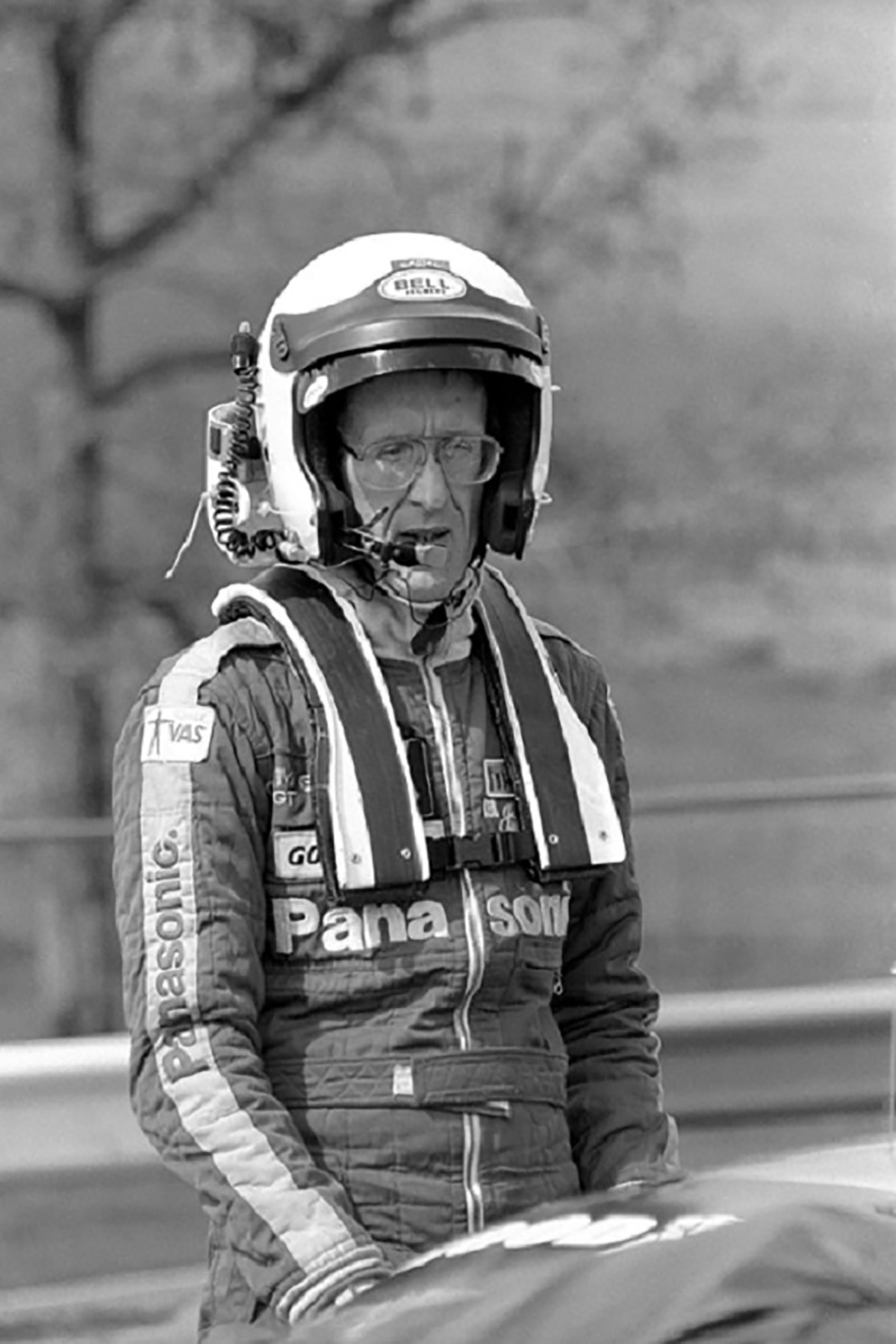

1989 March 31 | Friday: Jim Downing (63) Mazda driver tests a prototype of the HANS device in practice before the Nissan Camel Grand Prix International Motor Sports Association (IMSA) Camel GT event at Road Atlanta in Braselton, Georgia. Photo by David Allio

After the deaths of Adam Petty and Kenny Irwin from basal skull fractures earlier that year during two separate NASCAR events at the New Hampshire International Speedway, Helton was very interested in talking with Downing about motor racing’s first head and neck restraint. Since NASCAR closely controlled all aspects of its racing series, any safety device used by drivers had to have the sanctioning body’s approval.

Downing had met the future NASCAR president in the early 1980s while building Mazda RX-7 pace cars at his Downing/Atlanta race shop for the Atlanta International Raceway, where Helton was the general manager and in charge of securing the cars to fulfill a sponsorship deal financed by Mazda. Not long after that deal with Downing, Helton left his post at the Atlanta track to take a similar job at the giant oval in Talladega, Alabama, before moving to Daytona Beach as an employee at NASCAR’s Florida headquarters. Tall and broad with imposing eyes beneath a thick mane of dark hair, Helton had gradually worked his way up the NASCAR hierarchy.

“I knew Jim Downing from his racing days when he was the Mazda driver, when he was up in the wine country of Georgia and I was down in the moonshine country,” recalled Helton. “I knew Jim Downing as a racer. Atlanta Raceway had a deal one year with Mazda. We had Mazda RX-7 pace cars and they were souped-up by Downing. Bob Hubbard came along with that process of knowing Jim and in that time (after the driver deaths) we were getting more aggressive in talking with folks like that.”

Earnhardt wanted nothing to do with the HANS Device at the Indy test. “Dale came through the door of the NASCAR hauler, just walked right in while I was talking to Mike about the HANS,” said Downing of his first meeting with the driver known as “The Intimidator.”

“They had a little desk in there and he threw his leg over the corner of it and kind of sat down. He looked at us with that bristly mustache and a grin as if to say, ‘What are you guys talking about?’ The message was pretty clear. He didn’t want to have anything to do with the HANS and didn’t want Mike listening to what I had to say. Earnhardt sitting there pretty much brought the discussion with Mike to an end.”

Twenty years prior to meeting Earnhardt, Downing’s own experience with a head injury resulted in a fortunate outcome—given the dangerous nature of his crash on a track in Canada in 1980. On a sweltering August day at the Mosport Park track near Toronto, Downing was sweating profusely while competing in the Molson 1000. Onboard a Mazda RX-7 entered by the Racing Beat factory team, the tall, slender Downing was running first in the GTU class with the other Racing Beat Mazda immediately behind him in second place. Its driver, John Morton, was looking for a way past.

The 10-turn Mosport track undulates around glacially carved hills. Because of the almost non-stop high speeds, it’s a thrilling place to watch a race. On this summer day, fans, many of them camping overnight in tents on the various overlooks, had come out to see the World Championship of Makes race sanctioned by the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA). The race also paid points for the International Motor Sports Association (IMSA) and the combined entry featured some of the world’s best sports car teams and drivers.

This included numerous Porsche 935 Turbos, relatively crude silhouette cars. These ill-handling tube-frame machines were wicked fast due to turbocharged engines producing gobs of torque that hit the drive train like a thunderstorm. They were driven by sports car stars such as Brian Redman and John Fitzpatrick and by moonlighting Indy car drivers Rick Mears, Danny Ongais and Johnny Rutherford. Twenty-year-old future star John Paul, Jr. was another of those behind the wheel of the Porsches. The fearless and fast German, Walter Rohrl, co-drove a Lancia Turbo in search of FIA points and renowned team owner Bob Tullius of Group 44 was competing in a Triumph TR-8 for British Leyland.

In IMSA’s standard endurance racing formula, the GTU class for cars with smaller engines consisted of Mazdas, Datsun 240Z’s and Porsche 911 Carreras. While they relied more on momentum and less on horsepower, the GTUs were scary to drive at Mosport, too, because of their nimble cornering speeds—–and the constant swarm of faster Porsche Turbos.

During this particular summer, the heat and humidity were not unusual for August. But to find more speed, the engineer at the Racing Beat factory team had closed off most of the airflow into the cockpit. Downing had worked his way into the graces of Mazda’s racing management due to his quickness, reliability and low-key confidence that fit in well with the Japanese. He intended to sustain his career momentum and decided not to protest the lack of air coming through the cockpit.

Already a championship contender aboard Mazda RX-3s in the RS series of IMSA for compact cars running on radial street tires, he was looking to advance to the big leagues of American sports car racing and into the GTU category where Mazda was a major player. But he lost so much perspiration during the race’s first hour in the muggy cockpit that he passed out behind the wheel while heading into Turn Two—–a fast, sweeping, left-hand corner.

For the first and only time in his career, the crash briefly knocked Downing unconscious. Events became fuzzy as he was taken to the track medical center. It was like a dream—tumult, and noise all around him, but everything distant and one step removed, the roar of the cars on the nearby track now a distant hum. The memory lingered after an overnight stay in the hospital.

Patrick Jacquemart puts his amazing turbo-powered Renault through its paces at Mid-Ohio in 1981. He would be killed in a testing accident in the same car at the same track a few weeks later. Photo: Peter Gloede

“I just got lucky and the car turned backward,” recalled Downing. “It was a concrete wall with a hill behind it. The impact cracked and broke the wall. The car was so bad, they left it in Canada after stripping a few pieces off of it.”

Downing realized a head-on crash could have been deadly. (Five years later, Manfred Winkelhock was killed by a head-on meeting with the wall in Turn 2 on board a Porsche 962C during a World Endurance Championship race.) Downing began to think about the number of head and neck injuries happening in racing at the time. Like so many racers, he shrugged off his crash as part of the business. Then, the following spring, Downing learned that a frontal impact by fellow GTU racer Patrick Jacquemart at the end of the back straight of the Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course during a test was indeed fatal. The cause of death was a basal skull fracture.

Downing’s first reaction to his own near-miss typified the ambitious racer’s point of view, whether it was Formula 1, Indy cars, sports cars, stock cars or rallying. ‘It won’t happen to me again,’ he thought. But when Jacquemart’s crash occurred, the realization sunk in with Downing that it might have been his funeral. He then asked himself a once again: ‘Why can’t something be done about head injuries?’