by Luis Martinez

After trying to promote formula cars on ovals for its first couple of years, IMSA decided to switch its show to Grand Touring (GT) cars in 1971. The first IMSA GT race, the Danville 300, took place at Virginia International Raceway (VIR) on April 18, 1971. One of the avid spectators at the inaugural event was a U.S. Army Commanding Officer from Fort Lee, VA. The C.O. enjoyed that Sunday’s 3-hour race and the next day the Fort Lee Army Base newspaper, Fort Lee Traveller, announced the results. The C.O. discovered that one of the winning drivers of the #59 Brumos Porsche-Audi that not only won the GTU class but finished first overall was an Army conscript in his command – Army Specialist 4th Class Harris “Hurley” Haywood. Curious about this remarkable find, he summoned Haywood to present himself. When informed that he had been called, Haywood exclaimed, “Oh, (bleep)!”. Did Haywood, an active serviceman and Vietnam veteran, ask for leave to register as co-driver with racing veteran Peter Gregg? The rising IMSA Co-Champion replied with a grin: “I didn’t really ask for leave, I just sort of went.” Twenty-two year old Haywood went and chatted with his superior about the race. The C.O., realizing the talent and potential that Haywood exhibited during the race, comforted his conscript: “We have to accelerate your process-out paperwork!” How’s that for the quick application of a racing term to Army protocols?

One may ask, how did Haywood progress so quickly in life to run in front of the field for a win at the inaugural IMSA GT race? Two salient factors were in play: Haywood’s driving talent (schooled on his grandmother’s farm in Illinois), and an observant, experienced racer who recognized that talent and hired him. Haywood had often stayed at his grandmother’s farm. While there, he drove farm equipment and cars on private land learning handling techniques and getting a wheel ahead of his suburban peers. Meantime, Peter Gregg, a Harvard graduate and Navy Intelligence officer eight years Haywood’s senior, had become a successful Porsche racer. Having built an admirable racing portfolio in the middle of the 1960s, Gregg purchased an automobile dealership in Jacksonville, Florida in 1965, from Hubert Brundage – Brundage Motors. The cable address for this dealership was BRUMOS.

In the late 60’s Haywood was at college in Florida and had bought a used Corvette to compete at local autocross events. At one particular event, the experienced racer, Gregg, was also participating but the younger Haywood beat him anyway. Gregg normally won everything he entered so he decided to meet the talented youth. A friendship then ensued, a partnership that began with Gregg and Haywood collaborating to drive in the Six-Hour International Championship of Makes at Watkins Glen in 1969, winning the GT 2.0 class in Haywood’s orange #58 Porsche 911S.

But then war intervened. Haywood’s draft number came up for compulsory military service. He served a tour of duty in Can Tho, south of Saigon. While serving in Vietnam, Haywood learned a lot about situational awareness – constantly adjusting to unrelenting change while literally dodging bullets. These are lessons that he carried to podium finishes for decades as a highly successful endurance race driver.

In its inaugural year, IMSA’s classification of GTU was aligned with FIA Group 2 regulations for grand touring-type cars with engines of 2.5L displacement or less (the letter U referring to “under”). With so many cars to choose from, why choose the 914-6 for 1971? Haywood responds: “The 914 GT was a ton of fun to drive. The engine is just under 2.5 liters rated at 242 hp with two Weber triple-throat carburetors. It’s caged to stiffen the chassis, and Peter drilled holes in the door panels to lighten it. It had a dry weight of 2,098 lbs with a racing suspension, a 5-speed manual transmission, and 911-type calipers. Rear tires are oversized and fit in the enlarged, squared-off wheel wells. The tires were Goodyear, 7.5 inches in front and 8.5 rear, on 15-inch wheels. With a stock capacity 16.4 gal. gas tank, the car ran in GTU. In the race, the big bore cars would run from me but I would stay on them. Going into the corners I could brake better and eventually just wore them out. It’s a giant killer.” The 914-6 had arrived from the factory as a body in white. Brumos points out that orange tangerine was Dr. Porsche’s favorite color and to pay tribute Peter Gregg chose it for his race car’s livery.

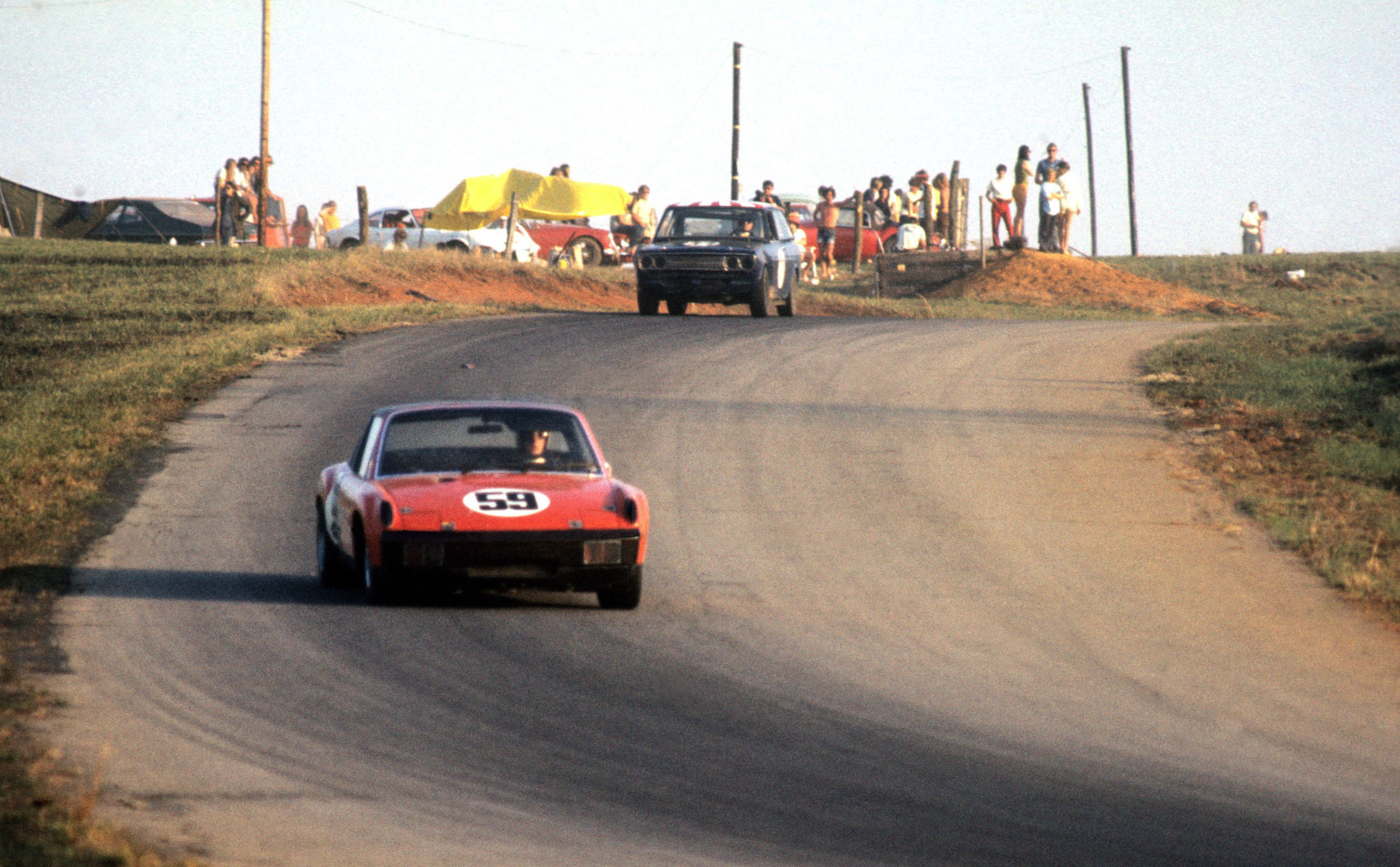

The Brumos Porsche 914-6 is seen approaching the Hog Pen corner at VIR in 1971. It was the overall winner of the first IMSA GT event ever held, beating out Dave Heinz’s more powerful Corvette in the process. Photo: Bill Oursler

The Danville 300 was actually Haywood’s third race of the 1971 season. He had already run with Gregg in the 24 Hours of Daytona where they qualified the same 914-6 in P1 but DNF’d on lap 260. A few weeks later they took the #59 car to the 12 Hours of Sebring and again qualified P1 in class and finished second in class. Haywood explains in his book, Hurley – From the Beginning, the crescendo of excitement that resulted from the win at the Danville 300: “We put the car on pole position for the class, this time starting on the front row with Dave Heinz and his 427 Corvette. That got some attention. Though the Corvette was fast and powerful, it was also heavier, with less braking power. When it started raining during the race, I found my groove and the 914 was amazing. I loved driving in the rain, especially in the perfectly balanced little car. By the end of the race we were a lap ahead in first overall, and it hit all the local papers including the Fort Lee base paper with a big photo of me on the front page.”

The car/driver combination of Porsche 914-6 GT and Gregg/Haywood proved unbeatable in IMSA GT’s first year: “ I actually owned that car when we raced it. After VIR we then went on to win our class several more times that year (Talladega, Charlotte, Bridgehampton and Summit Point) so Peter and I were co-Champions in ’71. We didn’t even bother running the 914-6 in the last race (Daytona) in November.” Haywood ran that race in a Porsche 911T.

Haywood and Gregg shared a Porsche 911S in traditional early Brumos orange at Daytona in November 1971. The car is seen here following Michal Keyser in a similar car through the infield section of the track. Photo: Bill Oursler

Haywood acknowledges in his book the positive impact that his tour of duty in Vietnam had afforded him: “The Army had changed me in ways I couldn’t have predicted. I was a calmer, more confident, cooler young man than that kid who drove at Watkins Glen in 1969. In terms of the racing itself, it was as if I never left. Instead of being rusty, my senses were sharper, my concentration more finely tuned.”

This observation about the success potential with Porsche as the ‘giant-killer’ among big-bore turned into a significant trend – from 1970 through 1984, the Porsche 917’s and other racing models accounted for 21 of the 26 overall victories in the two Florida classics – the 24 Hours of Daytona and the Sebring 12 Hours. “The 911 RSR was – and is – a great car to drive,” said Haywood, who scored three of his five overall Daytona 24-hour victories in that production-based car. “Back then, it was the car to drive because of its reliability. It was a really strong car, while the competition was not quite as reliable. The Porsche was not necessarily the fastest car on the race track, but it was certainly the most reliable.” That should settle the choice – should one go for sizzling raw power or boring reliability? Haywood is the living truth of an old saw – to finish first, you must first finish.

What happened after 1971? Haywood responds: “The 914-6 was sold and for a long time I lost track of it. I sold it to the Mexican Formula 1 racing driver, Héctor Alonso Rebaque.”

In 1972 John Bishop, co-founder of IMSA, secured a major sponsorship – R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., which put its Camel cigarette brand on the organization’s top series. As the title sponsor, the series became known as the Camel GT Challenge. Haywood remained on the roster for Brumos: “In 1972 I was given the job to run the GT car, a 911, #59 in Brumos livery and I won the championship outright.”

Over the years, the teamwork became well known, “Peter and I did so many races together, they called us Batman and Robin. We were virtually unbeatable in any car – the 914, the Carerra RSR, and the 935’s”. The driving duo lasted through the 1970s. “We had had an agreement that I would always race at least one race with Peter each year. We ran one or two races in 1979” until Gregg’s untimely death in 1980.

Besides the Danville 300 inaugural that Haywood vividly remembers, it was just two years later that ‘Batman and Robin’ registered for what became an epic race – the 1973 24 Hours of Daytona. It was in this race that the ‘dynamic duo’ unknowingly became the Porsche factory racing team. The factory had assigned two identical Porsche Carrera RSRs, which were effectively a prototype for the RSR still in development – one to Roger Penske’s team and the other to Gregg’s Brumos team. Gregg dismatled the car and noted that the flywheel was loose. He passed the information on to the Penske team but they failed to act on it. This proved to be a fatal error; Penske’s engine decomposed during the race and they DNF’d. Noting Penske’s failure Norbert Singer, then in charge of Porsche’s racing development, and his factory entourage came running to the Brumos pits which then took the mantle of ‘factory team.’ Singer then directed Gregg to tell Haywood to “slow down.” Haywood gave it only nodding attention – he had other problems – a seagull had penetrated Haywood’s windshield – literally. He needed to pit but they didn’t have a new windshield. The crew desperately “sourced” one from a spectator’s car. After the successful pit stop Haywood finished first overall. Because of that finish, the team handed the Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG factory its first international race victory using a Porsche Carrera RSR.

A single-spaced resume listing the interminable racing accomplishments by Haywood would be much longer than this article. Some of the highlights include wins at five 24 Hours of Daytona, three 24 Hours of Le Mans, two 12 Hours of Sebring, two IMSA GT championships, and one Trans-Am championship. Incredibly, Haywood started at the 24 Hours of Daytona a total of forty (40!) times by the time he retired in 2012.

Hurley Haywood at a Grand-Am event at Watkins Glen in 2010. Photo: Luis A. Martinez

But what happened to the #59 car, the tangerine orange Porsche 914-6 GT? “After I sold it to Rebaque’s father I lost track of it. Someone found it years later in 1988 in a field in Mexico. There are many 914’s out there but they called us about it. We sent our crew chief to confirm and we were able to positively identify it because Peter and I had drilled the door braces to lighten the car.” The Brumos team has meticulously restored the #59 car to its original specs and it now resides with the Brumos Collection in Jacksonville, FL.

Recent photos of the restored Brumos Porsche 914-6 at Amelia Island (photo credits: Anthony J. Bristol):

– Luis A. Martinez

The following is an excerpt from the book, IMSA: 1969-1989, by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Porsche’s dominance during the 1974 season began to weigh on John Bishop. He understood the Camel GT Series was not sustainable if it became a one-marque show. And he worried about escalating costs if European manufacturers like Porsche and BMW controlled the supply of the most competitive cars. He wanted to find a way to bring American manufacturers to the front of the grid and offer a cost-effective, competitive product to private teams. But how? The answer came to him on an airplane.

“The old system favored limited production cars like Porsches and BMWs,” John later recounted. “There was no way high volume, cheaper production cars could compete with limited production cars with better components. They were simply better cars. What we needed was an American car that could compete with limited production sports cars from Europe. In the middle of the 1974 season, I was on my way somewhere on an airplane. It occurred to me that Porsche was abusing the FIA Group 5 rules with the turbo-powered 934 and then the 935 with its wilder bodywork. The Group 2 and 4 rules limited what you could do with the bodywork but not so with the Group 5 rules. There was total disregard for the future of the class. We couldn’t ban the Porsches. So, I figured we’ll just do what they’re doing.”

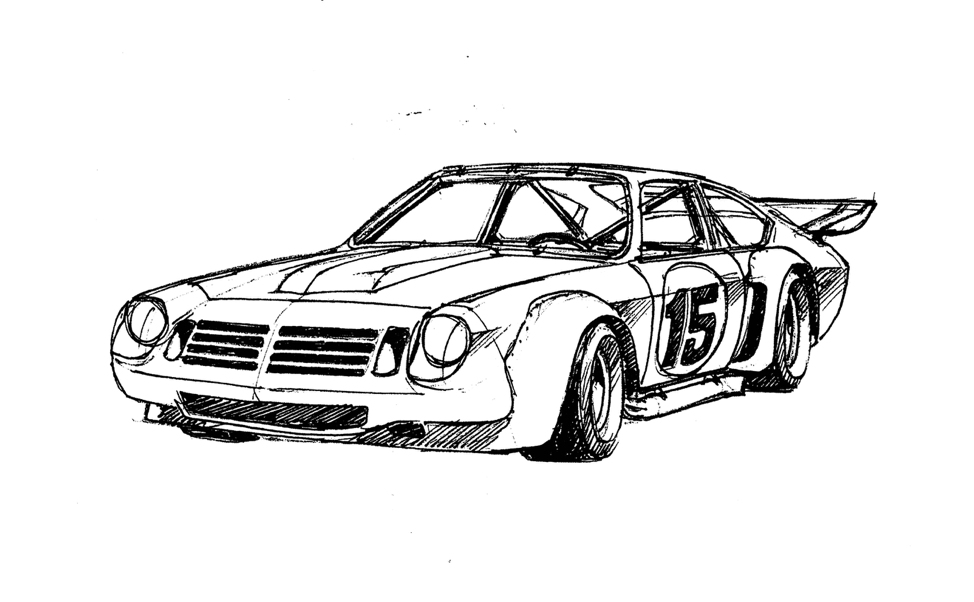

John Bishop’s original sketch of the All American GT concept he made on an airplane in 1974. This first concept drawing turned out to be very close to the first machines built for the AAGT class. Photo credit: Bishop Family

John Bishop’s original sketch of the All American GT concept he made on an airplane in 1974. This first concept drawing turned out to be very close to the first machines built for the AAGT class. Photo credit: Bishop Family

On the airplane, Bishop quickly sketched out his vision for American-based, tube-frame cars powered by readily available, low maintenance V8 engines, a class of cars that would be able to compete with the limited production, high-cost European Porsches and BMWs. He decided to call it All American GT (AAGT).

“The AAGT class was designed to allow tube-frame American cars to compete with limited production sports cars from Europe,” John recalled. “Porsche 935s were tube-frame cars at the end of the day. The only difference was that they rolled off a special production line in Germany, ready to race. The name AAGT came from our desire to give other people the same advantages that, by stretching the Group 5 rules, Porsche had enjoyed.”

Bishop started to share the AAGT concept in 1974 with some of the top competitors and at the end of the year IMSA published AAGT rules for the 1975 season. Steve Coleman and Amos Johnson debuted the very first AAGT car, a Chevy Vega they had built themselves, at the 1974 Daytona finale, where the car retired after managing just seven laps.

Steve Coleman and Amos Johnson’s home-built Chevrolet Vega, entered at the Daytona finale in November 1974, was the first AAGT in IMSA. Photo credit: ISC Archives & Research Center/Getty Image

“That was one of the overriding happiest reflections on IMSA,” remembered John later. “We could write a set of rules, talk about them with competitors, team owners and the like, publish the rules and then everybody would say; “Yes sir!” And they would go out there and spend money to build a car to those rules. We could create something great from just an idea.”

The new AAGT concept grabbed the attention of car builder and top engineer Lee Dykstra, who entered into a partnership with Horst Kwech in 1974 to form DeKon Engineering with the express purpose of designing, building and selling a competitive AAGT racer. With the direct assistance of Chevrolet, they began taking delivery of engines and other parts to construct the first wave of tube-frame Monzas. At just 2,400 pounds and powered by small-block V8s initially using Weber carburetors and later direct fuel injection, they produced 600 to 650bhp, making the Monzas balanced and lightning-fast. Purpose-built for racing, the only production parts appeared to be the roof and the windshield.

Kwech, already an accomplished racer, debuted the first production DeKon Monza at the Road Atlanta Camel GT doubleheader in April of 1975. He qualified fifth out of 40 cars entered, which got everyone’s attention, but retired after just 13 laps in the opening heat and didn’t start the second heat the next day due to teething issues. The bright spot was a privately built AAGT Monza driven by Tom Nehl, who finished eighth in both heats. The rest of the paddock began to see the potential of the new cars.

The first DeKon Monza campaigned in two races during the 1975 season. Australian Allan Moffat drove it at the Daytona 250-mile finale, on his way to a DNF after completing just fifteen laps. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com

DeKon Engineering continued to develop the car while another, privately-built version of the Monza arrived in the hands of Warren Agor, who finished a respectable 12th and 10th in the two heats at Lime Rock and scored another 10th at Mosport.

It was just a hint of things to come.

The AAGT concept gained speed with Porsche’s focus on the 934 and the Trans-Am for 1976. It put the top IMSA Porsche teams in a bind. Could they be competitive with the now-aging Carrera RSR against the BMW CSLs and new AAGT Monzas?

Al Holbert decided the answer was no. Although he had lobbied for the inclusion of the Porsche 934 for 1976, he preferred the larger rear wing, wider rear tires and lighter weight of the Monza compared to the RSR. Holbert purchased a DeKon Monza for the 1976 season and ran his first race at Road Atlanta in April with it after wisely sticking with the more reliable Porsche RSR for the longer Daytona and Sebring rounds. He finished second at the 24 hours of Daytona and won Sebring in March, co-driving with Michael Keyser, who then switched to the Monza.

By the Road Atlanta round in April, eight small block Monzas showed up from three constructors, including examples fielded by Keyser, Agor, Trueman, Nehl, Tom Frank and Jerry Jolly. There were many other AAGT cars as well: Coleman’s original AAGT Vega, five Greenwood- style Corvettes, Charlie Kemp’s wild Cobra II built by Bob Riley, and a host of Camaros led by the big orange No. 21 of Carl Shafer. Holbert and Keyser finished first and second in their DeKon Monzas, humiliating the rest of the field. The AAGT era had officially come of age.

Charlie Kemp’s wild AAGT Cobra II blowing smoke out the exhaust headers at Daytona. IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

Holbert went on to win four more races in the Monza to take the 1976 Camel GT championship. Keyser won two races with his version as well, cementing the future of American-built, tube-frame racers as the equal of anything produced on assembly lines in Europe. The Porsche Carrera RSR contingent included the usual faces along with George Dyer, Roberto Quintanilla, Bob Hagestad, John Gunn, John Graves, Monte Shelton, and others.

A host of Monzas head into the final turn at Laguna Seca during a heat race in 1977. Tom Frank leads Michael Keyser, Greg Pickett, Chris Cord, and Brad Frisselle, who took delivery of his car right before the race from Keyser and didn’t have time to apply graphics. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com

Al Holbert won a second consecutive Camel GT championship in 1977 in his potent AAGT Monza, updated with a larger rear wing, wider wheels, and more generous bodywork modifications that were allowed under new GTX rules. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com)

The AAGT revolution continued unabated for several years. Holbert won a second championship in a new winged Monza in 1977 against an onslaught of Porsche 934/5s. Other manufacturers became involved in the AAGT class, including Bob Sharp with the Datsun 280ZX twin-turbo V8. The bodywork, aero packages, and engines got so outrageous that IMSA dropped the AAGT moniker and changed the name of the class to GT eXperimental (GTX) in 1978. GTX became a combined class that included Group 5 Porsche 935s and all manner of AAGT machinery.

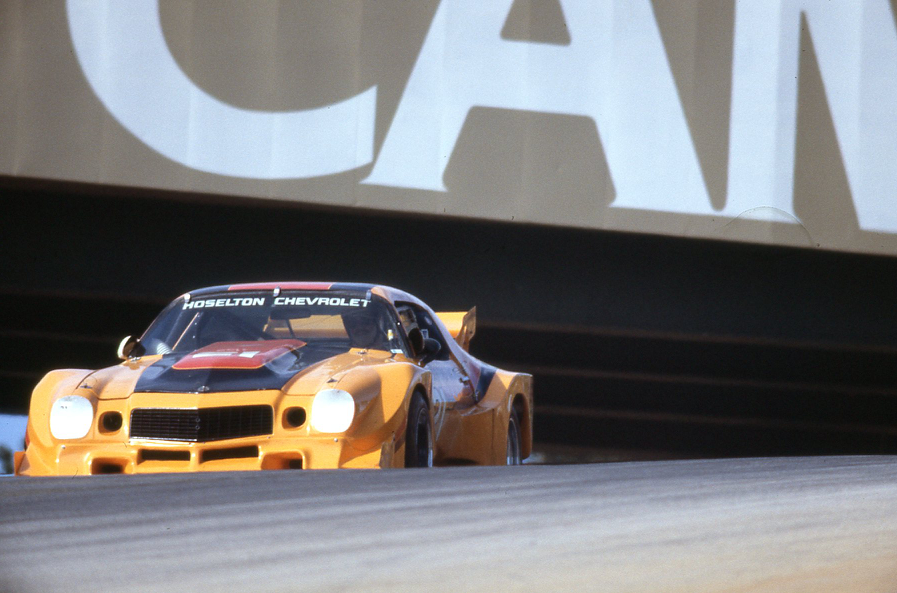

With rules changes that allowed for wilder bodywork, AAGT machinery continued to compete effectively with the Porsche 935 and the BMW turbo in 1978. Carl Shafer’s Camaro exits from under the bridge at Road Atlanta and starts the downhill plunge to the start/finish line. Photo credit: Bruce Czaja

As the founder of NASCAR, Bill France, Sr. was a force to be reckoned with. Physically intimidating but soft-spoken, “Big Bill” guided the growth of stock car racing with an iron hand into a powerful and popular regional sport in the 1960s. But many people don’t realize that Bill Sr. was also keen on establishing Daytona International Speedway, which he built in 1958, as a center for international motorsport.

In June of 1961, “Big Bill” and his son Bill France Jr. attended the Le Mans 24 Hour race as guests of the organizers. The sights and sounds of the cars were enticing but most intriguing were the more than 150,000 spectators filling the grounds of the track. This gave France Sr. an idea: could Daytona hold a similar style event and fill the stands? He reached out to his friend John Bishop, who was about to become the executive director at the SCCA, to help put the idea into action. As Bishop remembered: “When the SCCA went pro racing in 1961, there was an ACCUS meeting in New York City at the Drake Hotel. Bill Sr. invited me up for breakfast before the meeting and asked me: ‘Would you be interested in a new event? We’d like to get involved with the SCCA in putting on a major race in the early part of the year and we’ll call it the Daytona Continental.”

In the ensuing months, Bishop, and the two Frances had several meetings to plan what would become of the Daytona Continental that soon morphed into the 24 Hours of Daytona. The timing could not have been more perfect; the Club was just putting its professional road racing blueprint into motion and sanctioning the Daytona event would give it a much-needed leg up in that direction. Bill Jr. advocated for a 24-hour race from the start, but his father understood the need to ease into a longer event to avoid any political fallout with the Automobile Club de l’Ouest, the organizers of Le Mans.

The 1962 Daytona Continental three-hour race for sports and grand touring cars was held in February and fully sanctioned by the SCCA. Internationally famous drivers like Phil Hill, Jim Clark and Sterling Moss competed directly with top U.S. talent represented by A.J. Foyt, Dan Gurney, Walt Hansgen, Roger Penske and Briggs Cunningham. The race was won by Gurney, who coasted his Lotus-Climax over the finish line using only his starter motor since his engine had blown three minutes from the end of the race. In spite of a media tour held in New York the month before, attendance was light.

Fortunately, sports car racing (and Bishop) had an advocate in France Sr. He understood that it was going to take time to build an audience for this new spectacle and his vision of international recognition for Daytona intertwined with sports cars. This friendship culminated in France, Sr. coming up with the idea to start IMSA in 1969 and providing the funding to start the organization. Early IMSA races consisted of Formula cars (Fords, Vees, Super Vees) on ovals. But scary crashes and injuries in 1970 led IMSA to pivot towards sanctioning sports car races for FIA Group 2 and 4 GT cars. Aside from the 24 Hours of Daytona and the Watkins Glen 6 Hour, these cars had nowhere else to race for prize money during the season. It turned out to be the start of something big that eventually grew into the Camel GT Series starting in 1972.

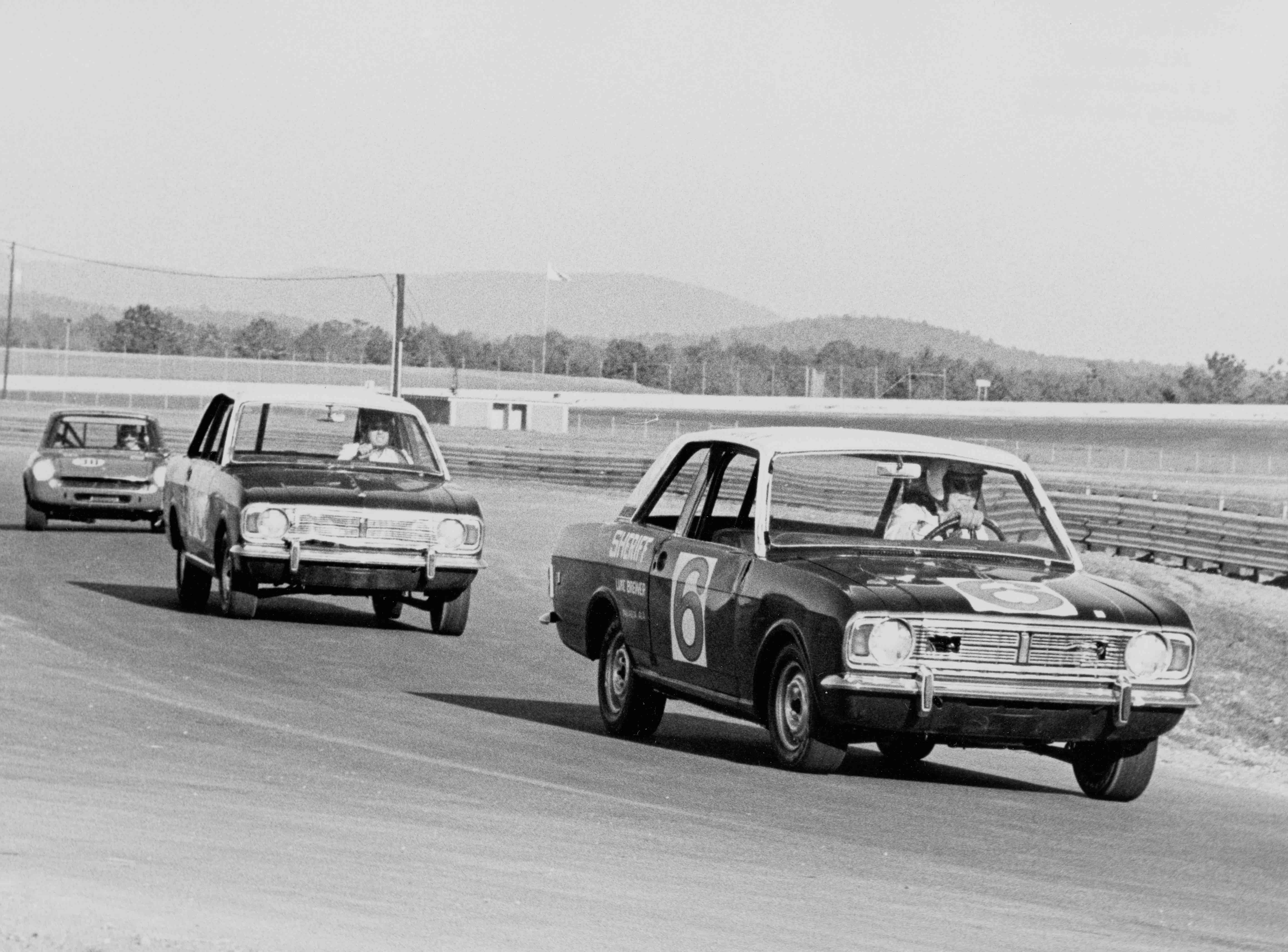

One of the earliest experiments with this category happened in November of 1970 at Alabama International Motor Speedway (now called Talladega). In a show of support, both Bill Sr. and Bill Jr. entered the race in matching Ford Cortinas that had been bought used from a local dealer and outfitted for racing. The ragtag field of cobbled-together machines included the founder and president of NASCAR and his son! Ultimately the son bested the father by finishing 9th in the race, while his father finished 17th. Here are some rare photos from the event.

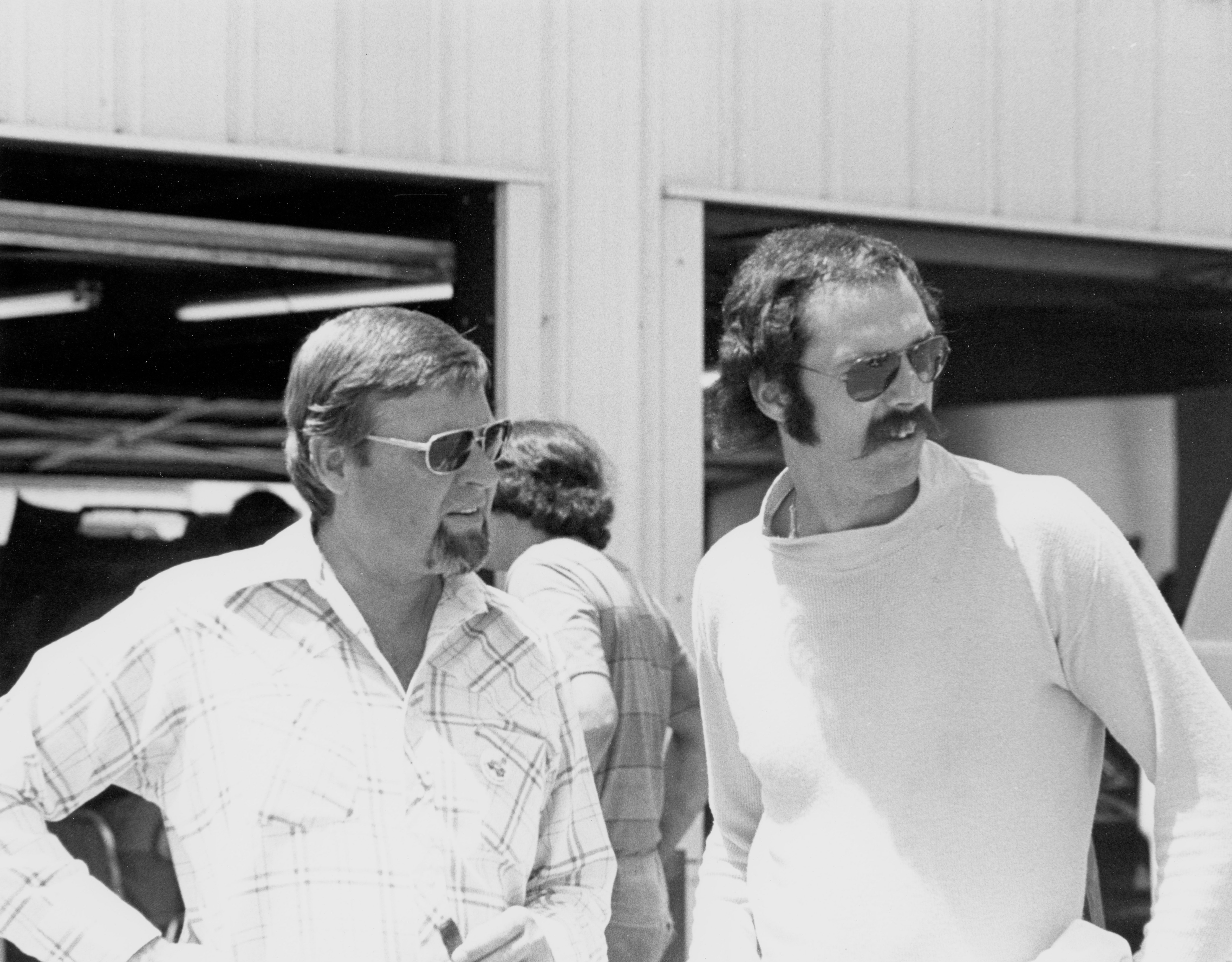

Bill France, Jr. (left) talks with his father, NASCAR founder Bill France, Sr., before the IMSA sedan race at Alabama International Motor Speedway in November 1970. Note that Bill Sr. is wearing a dress shirt and tie under his driving overalls! Photo: IMSA collection at the International Motor Racing Research Center

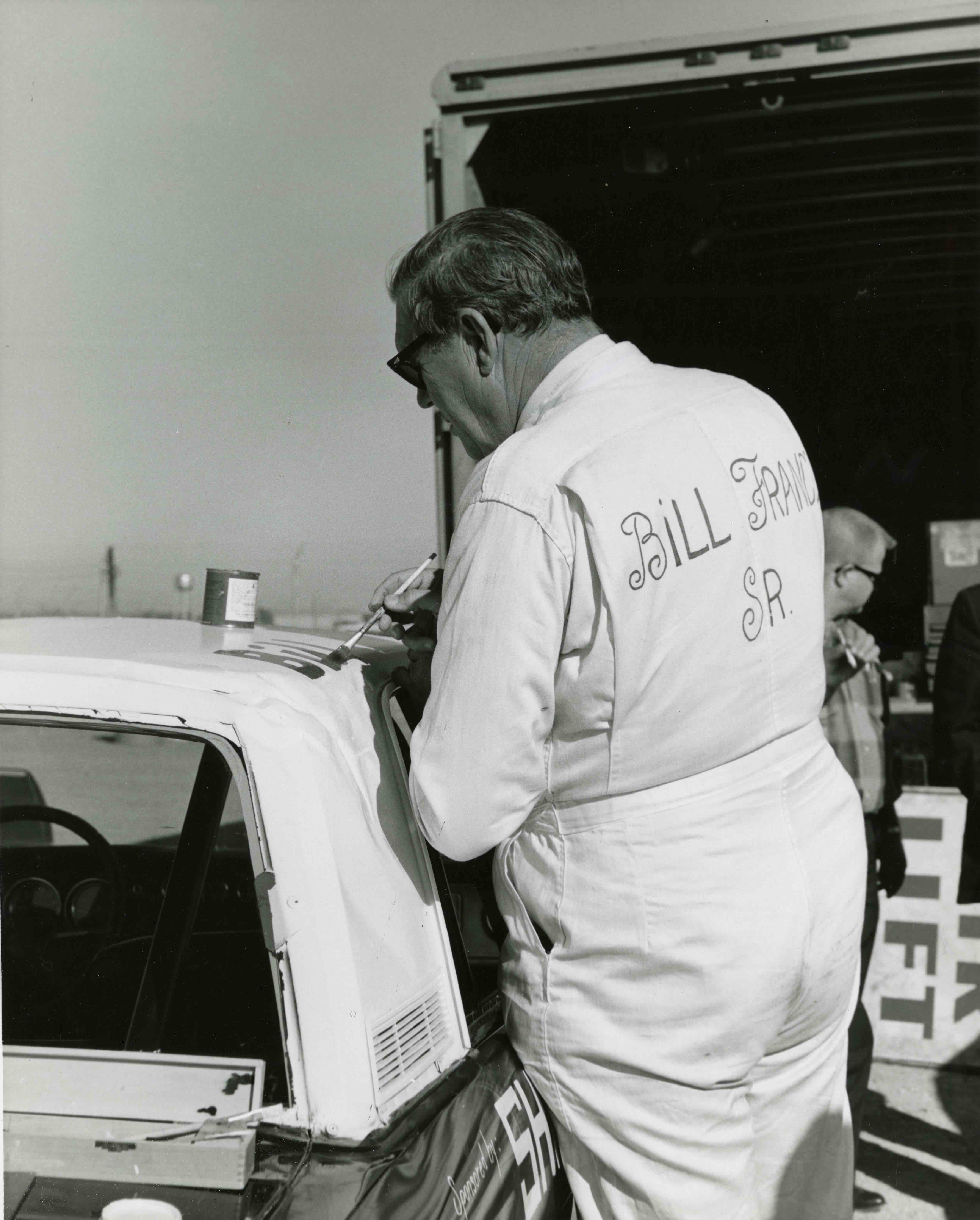

It was apparently a do-it-yourself kind of weekend. Bill France, Sr. paints his name on the top of the Ford Cortina he’s about to race in the IMSA event at the relatively new Talladega superspeedway in November 1970. Photo: IMSA collection at the International Motor Racing Research Center

Bill France Sr. leads Bill France Jr. in their Ford Cortinas at Talladega in November 1970. The younger France would finish 9th, ahead of his father, who finished 17th. Photo: IMSA collection at the International Motor Racing Research Center

Bill France, Sr. comes in for a pit stop during practice for the race. Photo: IMSA collection at the International Motor Racing Research Center

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” written by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf that tells the inside story of how IMSA got started and its first 20 glorious years. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Standing at just 5 feet, 6 inches tall, Charlie Rainville’s small stature didn’t seem at first glance to be a good fit in the high stakes, high-pressure world of big-time sports car racing. But competitors and manufacturers that underestimated him quickly learned the hard way that Charlie was not a man to be trifled with. He was tough as nails, a kid that grew up on the wrong side of the tracks in Providence, Rhode Island. He was street smart, savvy and ready for a fight. But he was also immensely clear thinking and eminently practical when it came to managing the many conflicting personalities that were each vying for an unfair advantage. The ever-present twinkle in his blue eyes and ready smile were Rainville’s main weapons for disarming tense situations, but he also commanded immense respect from competitors familiar with his experience.

One of the original pioneers of U.S. road racing, Charlie had earned a reputation as a tough competitor and brilliant race car preparer, starting as a mechanic at Jake Kaplan’s Import Motors shops in Providence in the late 1950s. Known for being able to massage anything to go faster than originally intended, he was the go-to guy for preparing sports cars in New England for the growing groups of enthusiasts importing them from Europe. Charlie became an expert on all of the exotic cars of the day, including Alfa Romeo, Jaguar, Lotus, Ferrari, Porsche, OSCA, Iso Grifo, Datsun, and Corvette. In addition to engines and suspension setup, he became a true artist, hand forming aluminum body panels for all sorts of makes and models.

An accomplished racer, Charlie Rainville drove for the factory Plymouth Trans-Am team in 1966, including the opening round at Sebring, where the Trans-Am cars had a four-hour race ahead of the 12 Hour classic. Photo: REVS Institute

As a driver, Rainville had a brief career in sprint cars and on short tracks until he gravitated to SCCA track events, hill climbs and rallying in the New England area, campaigning in aluminum- bodied XK120 Jaguars, Alfas, OSCAs, and Cobras. He then jumped to the professional ranks by competing in SCCA Trans-Am series events in Barracudas as part of the first works team from Detroit in 1966. A few podiums and a fifth-place overall finish in the points that first year of the Trans-Am would mark the pinnacle of his driving career. Along the way, Charlie built a reputation for helping anyone in the paddock with parts, labor, and advice, and then going out and beating them on the track.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR: Don’t Lean Too Hard on the Doors

The cars for the first-ever Trans-Am race were run as a separate class at the Sebring 12 Hour in 1966. As both John Bishop and Charlie Rainville relayed it, they met on the grid just before the race. John went over to the driver’s side of Charlie’s car to wish him good luck in the race. As he leaned in on the door to talk, the door started collapsing. John knew that the SCCA had approved alternative thin steel door panels for the Plymouth, but he was unprepared for how thin! Charlie laughed and promptly pounded the panel back out with his fists from inside the car and made no reference to the fact the door was, in fact, aluminum which, needless to say, was not a standard Barracuda part in 1966. John gave his apologies for damaging the car, along with a wry smile and walked away. Charlie went on to finish seventh that day.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By the end of the 1960s, Rainville had retired from racing and evolved into one of the top SCCA race stewards in the country. He and Bishop had crossed paths many times by this point. Bishop saw that Rainville’s view of how racing should be conducted matched his own and when the opportunity came to forge a partnership of philosophies, he became the obvious choice to lead the charge for IMSA at the track when it came to technical and competition matters.

The man who made the tagline “Racing with a Difference” come to life at IMSA events for many of the participants was Rainville. He was IMSA’s chief steward, race director, technical director and director of competition from IMSA’s start through the early 1980s. In appointing him to these positions, Bishop understood that Rainville brought decades of useful experience in car construction, race preparation, competition driving and race officiating to the table. He knew instinctively that Charlie would command immediate respect from competitors, team owners, race organizers and manufacturers.

The solid partnership forged between Charlie Rainville and John Bishop made IMSA tick for many years. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

Rainville’s no-nonsense, common sense approach to technical rules, race regulations and race management confirmed he was the logical choice to run the competition side of the new organization. He introduced a new style of series management: benevolent dictatorship, something competitors had not experienced in the highly political world of the SCCA.

Hurley Haywood had this to say about Rainville: “He would look at the situation and say, “That’s a good idea,” or “No, that’s not a good idea.” There was no discussion. Whatever he said was final. You could talk until you were blue in the face, and you weren’t going to change his mind. Most of the time, he was pretty reasonable. John softened these situations by playing the ultimate diplomat. John would never put his foot down and say “This is the way it’s going to be. You’re going to do it my way or hit the bricks.” John always left the door open where you could see some light shining through. There was always hope.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR: The Chopped Camaro

One story that illustrated Charlie Rainville’s practical approach to policing rules happened at Laguna Seca in 1976. Carl Shafer, a regular on the IMSA circuit in his orange Camaro, had towed all the way to California along with a bunch of other East Coast competitors. At the time, IMSA was still building a foothold with the West Coast races and needed every entry it could get. As the Camel GT cars were sitting in pit lane, waiting for practice to begin, Charlie stood next to Shafer’s Camaro, just staring at it long and hard; something just didn’t look right. Charlie called Shafer over and the two of them faced each other. Shafer was 6 foot, 3 inches tall, so he towered over Charlie, who asked him: “The car doesn’t look right, Carl. Did you chop it?” Shafer, knowing he had been caught, looked down and replied in his slow Midwestern drawl: “Yeah Charlie, I did.” Turns out the car’s roofline was four inches too short from the standard Camaro template. But rather than throw him out and not let him race, Charlie told him to weld a four-inch spoiler to the top of his roofline, which the team did that night. It looked like hell and acted as a boat anchor at speed, but at least he didn’t have to tow home to Wyoming, Ill. without racing and IMSA had another car in the field.

Michael Keyser leads the first lap of the Camel GT Challenge race at Laguna Seca in 1976. Al Holbert, Peter Gregg, and Carl Shafer follow. A four-inch spoiler is visible on Shafer’s Camaro, mandated by Charlie Rainville after IMSA found that the roofline had been chopped. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR: Passing Tech Inspection

Jim Busby recalled: “Charlie’s policing was fascinating to me. We’d be doing something really bad, so far out of the box that it was ridiculous. One example was when we modified the wheelbase of a Porsche Carrera RSR to take the weight off the rear end. Having the weight there was great, for the first half of a stint, but we burned off the rears after that. We had to find a way to move weight forward.”

“Right before Mid-Ohio one year, I got to thinking. What if we just move the holes in the fenders forward like three or four inches and move the engine forward three or four inches and misalign the half shafts forward three and a half inches? We made Porsche A-arms that looked stock but moved the wheelbase forward, which shifted the engine and transmission weight forward and shortened the rod that went from the shifter to the transmission and off we went. We took the car to Mid-Ohio and were getting ready to race, but first, we had to get the car through inspection.”

“We’re standing there in the tech shed and Charlie was standing there looking at the car, then looking at me. Over and over again. Back and forth between the car and me, like he was asking with his eyes: “You’re up to something, I just don’t know what it is yet.” Finally, I turned around and I looked at him and he looked at me and he had a look in his eye like, “Is there something you want to tell me?” I responded: “Oh hey, Charlie! How are you?” He nodded his head and walked away. John did that to me a lot too. His patience for me would really grow thin.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Charlie’s stature within the SCCA was solid and influential, particularly the corner workers and other officials. He felt most at home with the hundreds of volunteer officials and course marshals that showed up every race weekend. This allowed him to diffuse some of the early politics that the SCCA had with IMSA. The workers respected him and loved working with him at the track. He quickly added a number of key SCCA stewards, notably, Roger Eandi in California, K.C. Van Niman in the Midwest and Charlie Earwood in the Southeast into IMSA’s fold as race officials. They remained a significant part of the organization for the balance of their careers well into the 1990s.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR: Shicklegruber Fuel Injection

Mark Raffauf remembers a classic Charlie Rainville story: “Charlie worked in the IMSA office in Connecticut a few days a week when there wasn’t a race meeting to attend. Although he was an integral part of the behind-the-scenes rules process, Charlie wasn’t really at home working in an office. He preferred the smells, the grime and the comradery of the track or garage. We were working on finalizing the rule book for the 1977 season when one day, Charlie walked into my office and asked: “What’s the name of the fuel injection that BMW wants us to allow for the 320i?” Both Roger Bailey and I answered: “Kuglefischer.” Charlie thanked us and went back to his office. A month later, after we published the rule book, we received a frantic call from Jim Patterson, who ran BMW’s racing program in North America at the time. Apparently, Charlie had published the rule book with the name of the approved BMW fuel injection as “Shicklegruber,” which is how Charlie apparently translated “Kuglefischer.” We never lived it down with the BMW folks.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

John Bishop and Rainville together forged a philosophy and organization that set new standards of professionalism, communication and empathy that were soon copied everywhere. Although emotions often ran high, drivers respected the decision-making process and often would admit that it was fair, even if it went against their position. Charlie looked out for the competitors in ways very different from previous attitudes about the relationship between officials and participants. They were his drivers and he went to great lengths to take good care of them. And he started every day with a clean sheet of paper, nothing from the previous day was held over anyone.

Charlie Rainville and John Bishop in 1979. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

The staff that worked for IMSA were mentored and taught how to do the right thing, how to be straight-forward and how not to be afraid of making decisions or the resulting consequences. Sure, mistakes were made, but Rainville was generous and forgiving the first time. The second time was not so pretty. From this process, a new generation of professionally trained, full-time officials was developed who eventually held the reins well into the 1990s. Because of this training, when Charlie retired in 1983, the transition to Mark Raffauf was virtually seamless. Though still attending the races for another year he never injected himself into the activity unless asked, but he was always there for support if needed.

When Rainville passed away in February of 1985, sports car racing lost one of its true pioneers. At the time, Ken Parker of the Providence Journal-Bulletin wrote; “No man is irreplaceable, but one cannot help but feel a twinge of sympathy for the person who steps into Charlie Rainville’s shoes. During his many years as Racing (and Technical) Director of IMSA, Charlie was known, loved and respected nationwide, not only for his competence but also his fairness and quiet generosity. John Bishop, President of IMSA, gives Charlie much of the credit for making IMSA the world’s foremost professional racing organization, and Charlie raised IMSA to that level in less than 10 years.”

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” that tells the inside story of how IMSA got started and its first 20 glorious years. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

BMW of North America’s racing group was established in 1975 in an effort to support the company’s growth in the lucrative US performance car market. Unfortunately, the company did not have an IMSA championship to show for the investments in the BMW 3.0 CSL and the turbocharged BMW 320i. With just one or two cars pitted against a host of Porsches, the odds were not in their favor. The tube frame M-1 Procar did crush the GTO competition in 1981 but was underpowered in IMSA’s top GT Prototype (GTP) class.

Something had to be done to narrow the gap. Former SCCA executive Jim Patterson, who took over the BMW North America racing program in 1978, saw the newly minted IMSA GTP rules in 1980 as a way to get back in the game. Working with partner March Engineering, a unique new prototype was unveiled in early 1981 that would become the basis for a long, successful supply of GTP cars to the IMSA field from the British company.

The BMW M1/C debuted at Riverside in April 1981. The March chassis featured a modern aluminum monocoque that was mated to a normally aspirated 3.5-liter BMW engine. The team would upgrade to a 2.0-liter turbocharged motor later in the year. Photo: Don Hodgdon

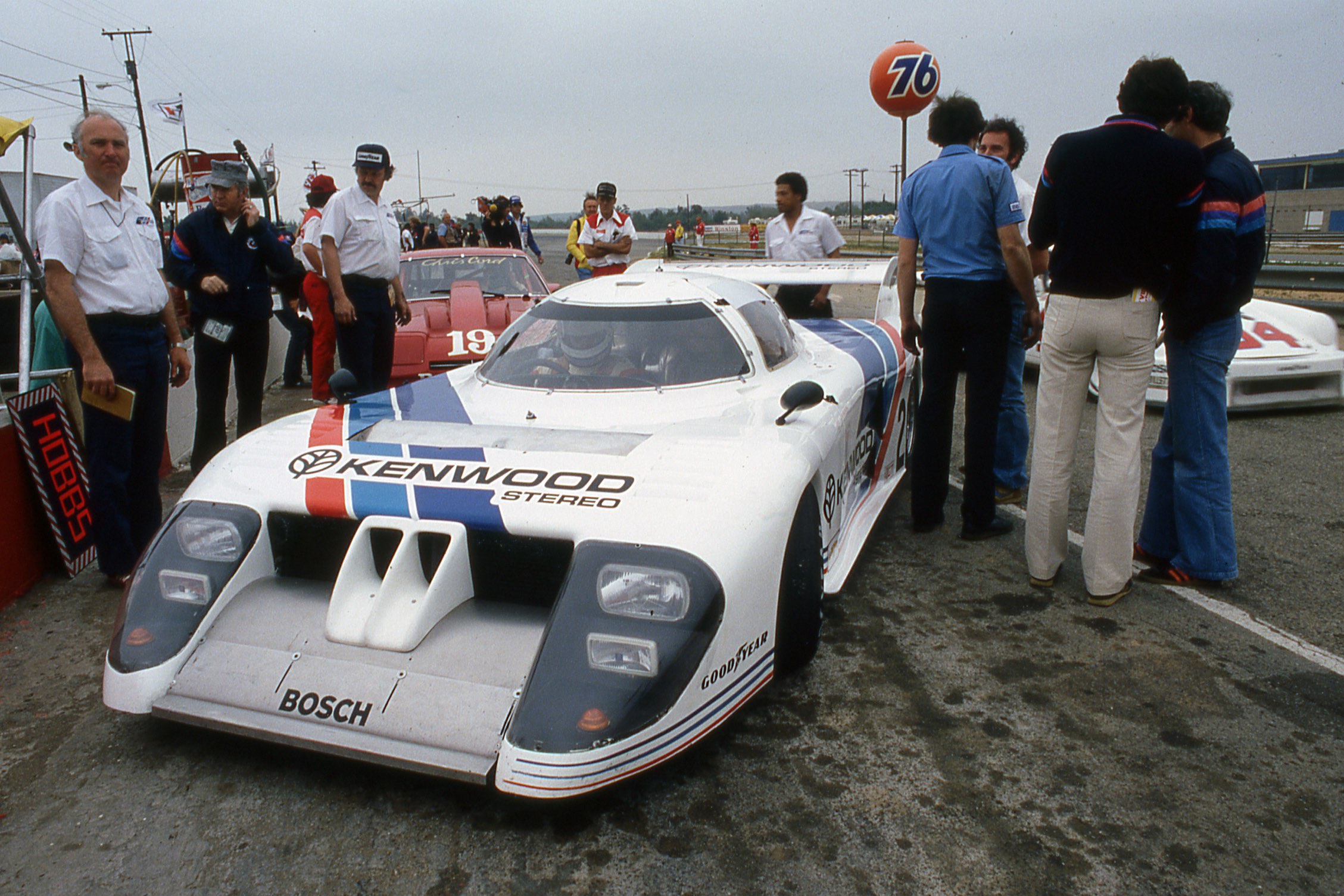

Designed by French aerodynamics expert Max Sardou and BMW engineer Raine Bratenstein, the car was dubbed the BMW M-1/C. It was built around a March Engineering aluminum monocoque and featured two distinctive pontoons at the front that were designed to channel airflow to both the radiators and twin ground-effects tunnels for maximum downforce. The car was initially fitted with a 3.5-liter, six-cylinder, normally aspirated BMW engine, and entered for the first time at the Riverside 6 Hours in April 1981 with David Hobbs and European endurance veteran Marc Surer at the wheel. Featuring sponsorship livery from Kenwood audio, the pair finished a credible sixth place, albeit eleven laps down to the winning 935 piloted by Fitzpatrick and Busby.

The lone BMW M1/C is swamped by a host of Porsche 935s at the start of the 1981 Riverside Camel GT race. The M1/C would go on to finish sixth, eleven laps down from the winning Porsche 935 of John Fitzpatrick/Jim Busby (#1). Photo: Don Hodgdon

A week later at Laguna Seca, Hobbs placed sixth again, this time one lap down to the new Lola T-600 with Brian Redman at the wheel. Although down on power, Hobbs managed to put the car on the front row at both Lime Rock and Mid-Ohio. The first few races proved the M-1/C had real potential and the decision was made to further develop the chassis and engine. The long-term plan was to install the 1.5-liter turbocharged BMW motor being developed for Formula One, but that engine wasn’t ready and would never be used in the March. Instead, the team force-fit the same turbocharged 2.0-liter, four-cylinder engine that had been used successfully in the McLaren-engineered BMW 320i program. Since the M-1/C had not been designed for that power plant, it required a cooling workaround for a motor that produced 600 to 675bhp with the boost turned up.

Results were mixed after the change. The new engine debuted at Sears Point in August. The car was fast and competitive, but ultimately unreliable. A fourth place at Portland would turn out to be the team’s best finish. Despite stating long-term commitments early on, BMW again left IMSA racing at the end of the year, this time to focus on its Formula One program.

Even with this setback, March Engineering took what it had learned from the M-1/C experience and produced a viable, stable GTP customer car for 1982, dubbed the 82G, that was designed by Gordon Coppuck. The first two customer March 82Gs appeared in January for the 24 Hours of Daytona. One of them was a Chevrolet V8-powered version driven by Bobby Rahal and Jim Trueman and fielded by Garretson Enterprises. Rahal would campaign the car in later rounds with Michelob backing.

The first March 82G customer car was fielded by the Garretson team at Daytona in January 1982. Photo: Bob Harmeyer

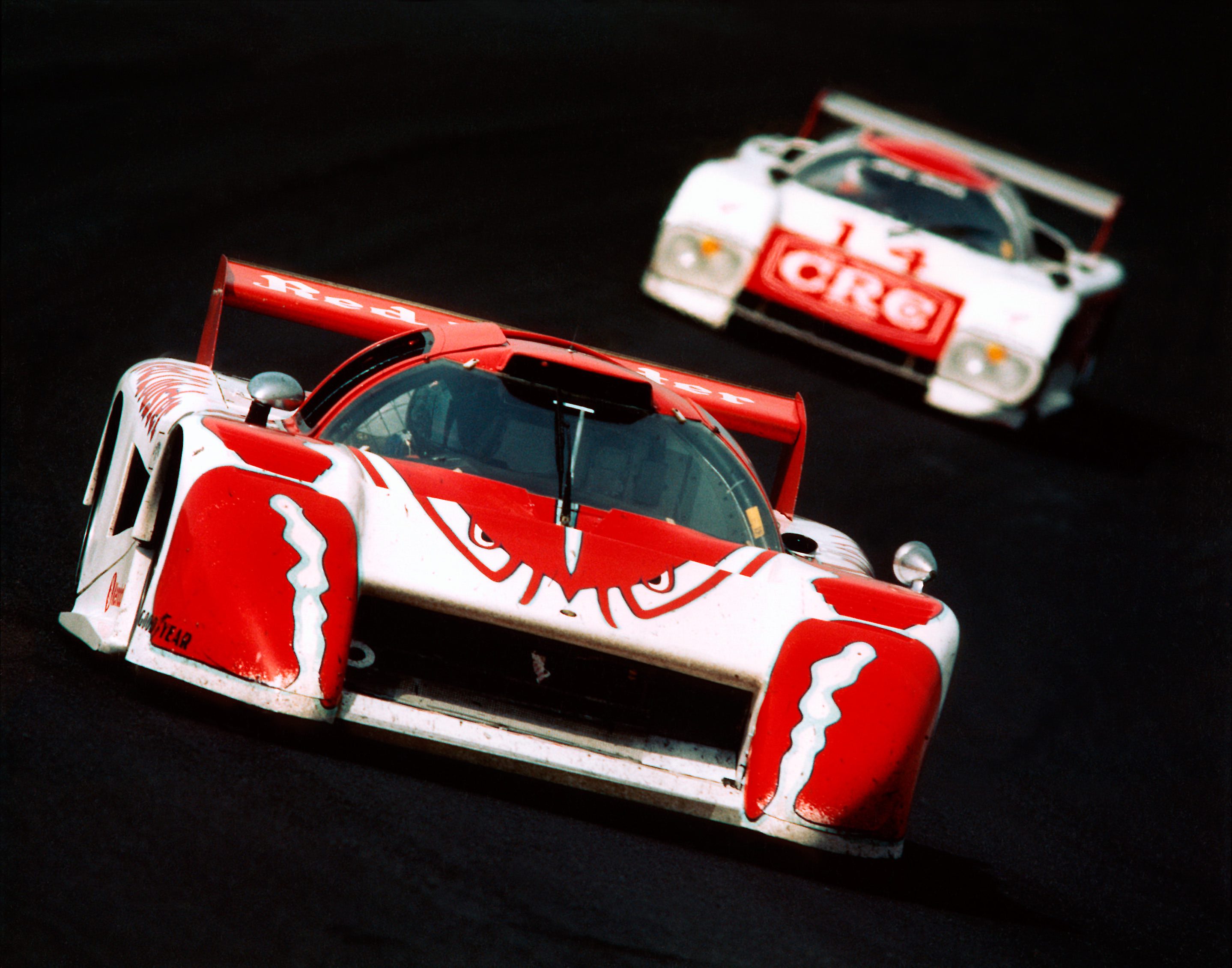

The other March was campaigned by Dave Cowart and Kenper Miller’s Red Lobster team. After winning the 1981 GTO championship in the dominant BMW M-1, the team commissioned an 82G from the March factory with the now well-tested 3.5-liter BMW M-1 engine. The distinctive twin pontoons of the March turned out to be a perfect canvas for two Red Lobster claws, a design that became iconic almost instantly. Unfortunately, the normally aspirated BMW engine was no match for the Chevy V8 or Porsche 935s, and for 1983 the team campaigned with Porsche 935 turbo power, only to suffer from overheating issues. The team took the midsummer Daytona race off in 1983 and came back later in the year with Holbert’s second March 83G powered by a Chevy V8.

The twin pontoons of the March 82/3G were ideally suited for the paint scheme of the Red Lobster team, pictured here in 1983 at Daytona, leading the similar Porsche-powered March of Al Holbert. Photo: Richard Bryant

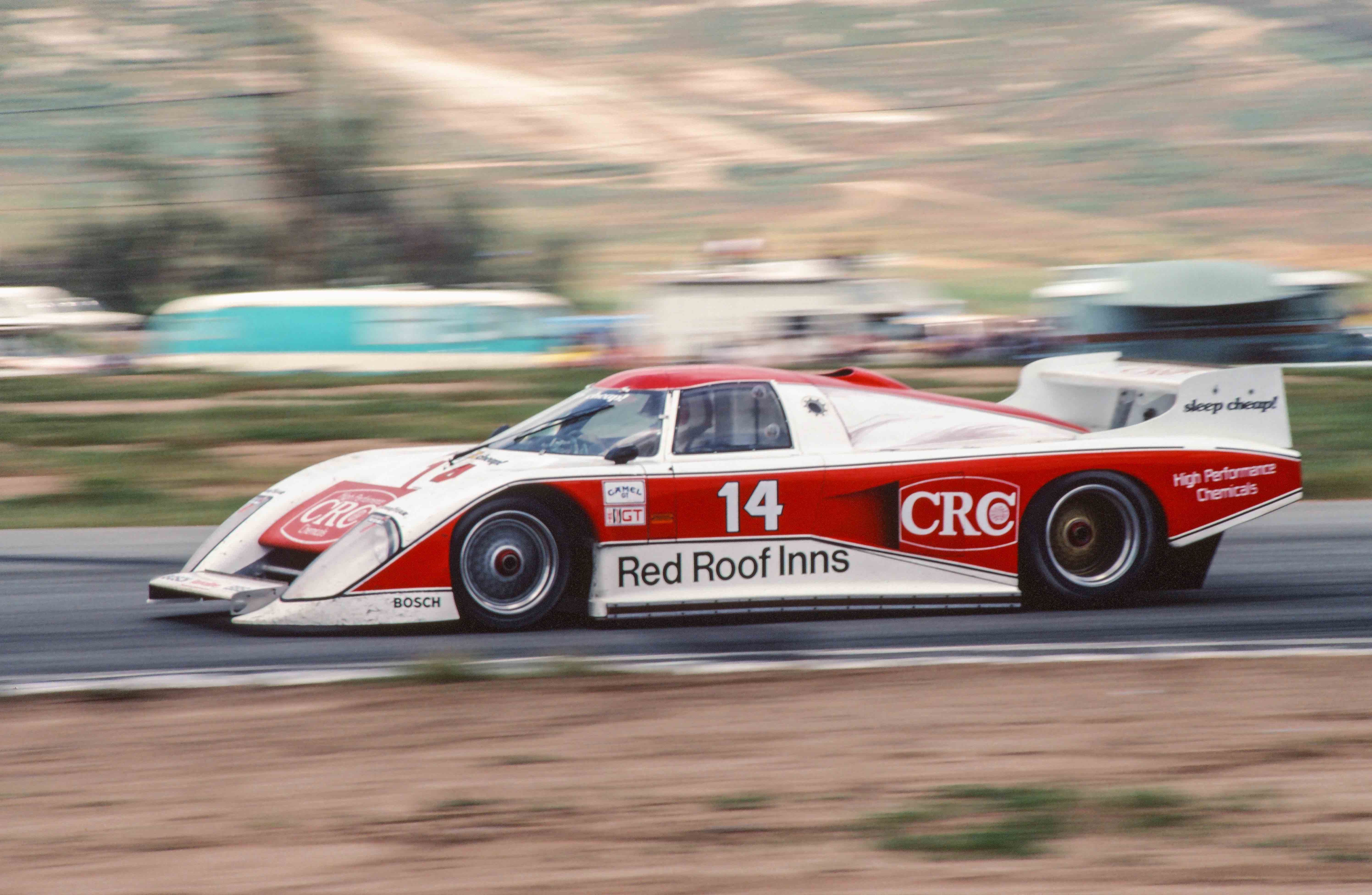

The biggest news of the 1983 season was the return of Al Holbert, who had been pursuing Indy Car and Can-Am glory. Holbert started the season by sharing Bruce Leven’s Bayside Disposal 935 with Hurley Haywood at Daytona and Sebring. But his main focus was on a CRC Chemicals–sponsored March 83G, initially fitted with a small-block Chevy V8. Holbert won with the car the first time it was entered, at the inaugural, but rain shortened, Grand Prix of Miami. After skipping the Road Atlanta round, Holbert finished second at Riverside and won Laguna Seca, after which he sold the car to Kenper Miller and Dave Cowart’s Red Lobster team.

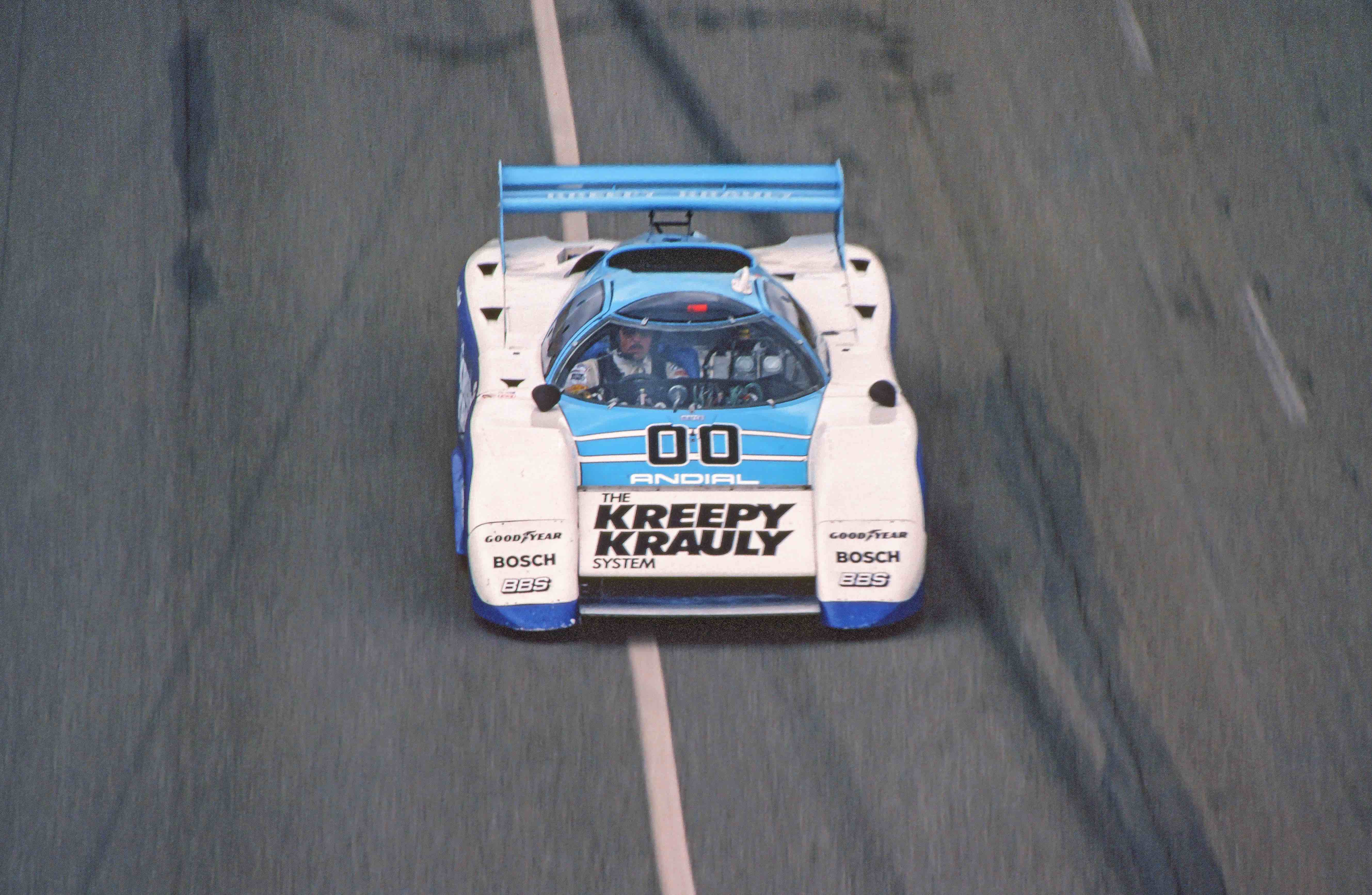

Holbert had another ace up his sleeve: a brand-new March 83G, this time fitted with an ANDIAL-prepared Porsche 934 single-turbo engine. Despite skipping the Mid-Ohio and mid-summer Daytona events, Holbert easily took the 1983 Camel GT title by winning with the new Porsche-powered car four times and scoring points in another seven races.

Al Holbert’s triumphant return to IMSA competition in 1983 came at the wheel of a March 83G fitted with small block Chevy V8, shown here at Riverside. He later switched to a new March 83G chassis fitted with a single turbo Porsche 934 motor and won the 1983 Camel GT championship. Photo: Kurt Oblinger

One of the prettiest GTP cars of the era, the ex-Holbert Racing Porsche-powered Kreepy Krauly March 83G of Sarel Van der Merwe, Tony Martin, and Graham Duxbury, won the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1984, pictured here at Riverside in the 1984 season. Photo: Kurt Oblinger

The Blue Thunder Marches of Bill Whittington and Randy Lanier, sponsored by Apache Powerboats, dominated the 1984 Camel GT season with six wins, including one here at Watkins Glen, giving the title to Lanier. Photo: Whit Bazemore

With the introduction of the Porsche 962 into the Camel GT Series in 1984, it wouldn’t take long for Porsche to once again dominate U.S. sports car racing. The 1984 championship in the hands of Randy Lanier driving a Chevy-March would turn out to be the last for a March-based car in the series. But not without a fight.

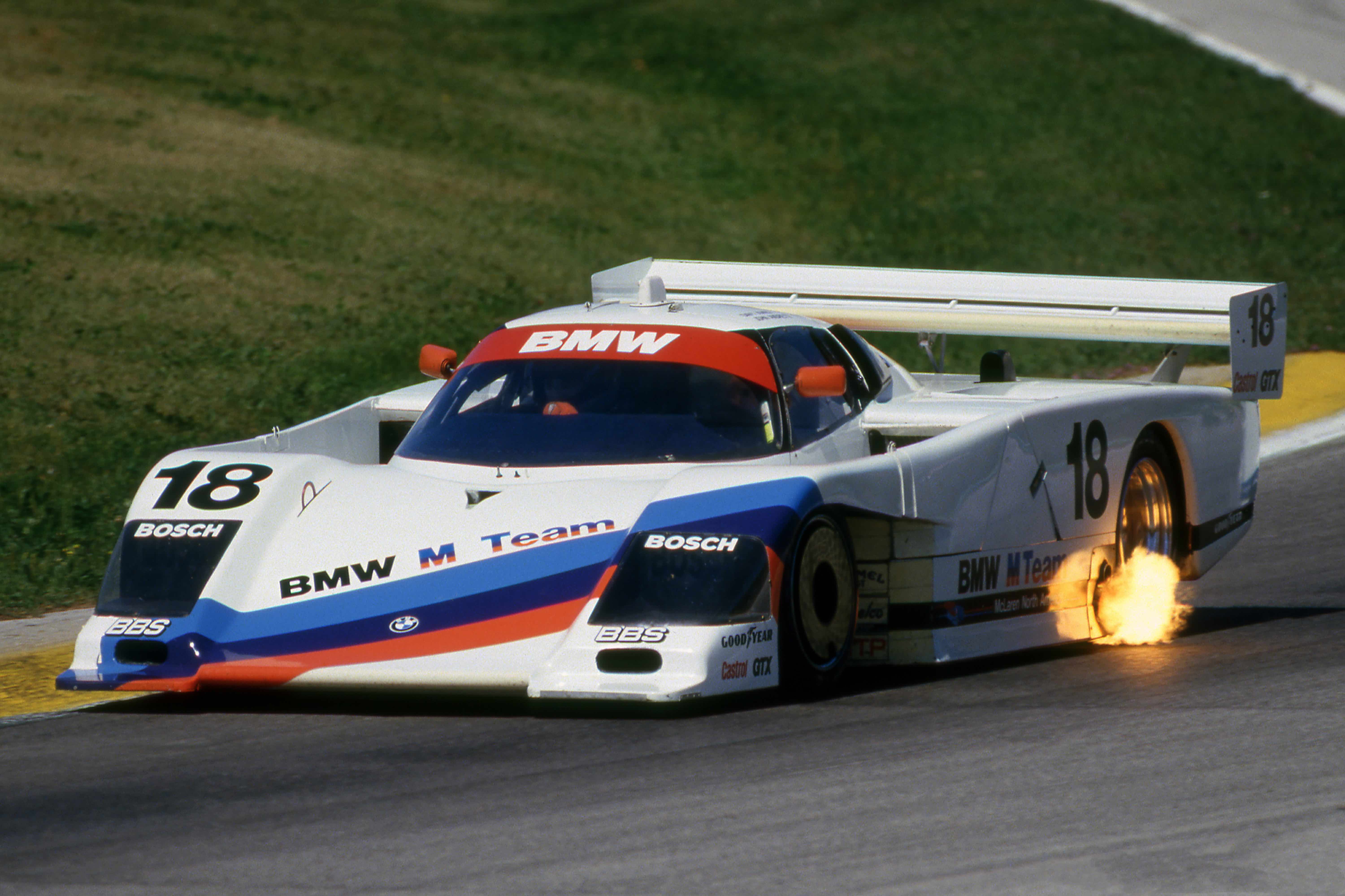

BMW decided to renew its Camel GT program by entering a March 86G chassis for David Hobbs and John Watson in the 1985 season-ending race at Daytona. As before with the 320i program, McLaren North America prepared the cars and ran the team. By this time, BMW’s 1.5-liter turbocharged Formula One engine was well developed and reliable. It was the same engine used by Nelson Piquet to secure the 1983 Formula One World Championship. It was adapted in a 2.0-liter form for the March 86G, the first prototype designed entirely using computer-aided design equipment. Power output was a reputed 1,100bhp with the boost turned up.

A second car for John Andretti and Davy Jones was built early in 1986, but during testing at Road Atlanta, it was destroyed in a fire caused by a fuel line that had been loosened by an engine vibration. The same vibration caused a serious, end-over-end crash in practice at Sebring when the rear cowling flew off, destroying a second tub, and forcing the team to withdraw.

Given the teething issues and destroyed cars, Bob Riley and a host of all-stars were brought in to help sort things out. After working flat out, the team turned the BMW-March into a very fast but still inconsistent car. The team skipped a few races during the 1986 season, but the car’s outright speed was evident whenever it showed up. After winning the pole at Road America, Jones survived a horrific high-speed crash in the race just after the kink in the backstretch when he put two wheels off in the grass on driver’s left. Bad luck and mistakes seemed to dog the team.

The BMW March 86G was a generation ahead of the rest in terms of aerodynamic grip and raw speed in 1986. Reliability issues kept it from doing well much of the season. Photo: Bob Harmeyer

However, the team’s triumphant moment arrived in one spectacular win at Watkins Glen with Andretti and Jones at the wheel. The two BMWs started on the front row and the winning car lapped almost everyone else in the field. In spite of the promising result and the car getting faster without direct factory support from Germany, BMW once again withdrew from IMSA after the Daytona finale at the end of 1986. David Hobbs lamented the decision, saying, “We could have cleaned the table with that car in 1987, it was probably the fastest prototype I ever drove.” Two of the March 86G chassis were sold to Gianpiero Moretti, who installed Buick V6s (one was a turbocharged 3.0-liter and another was a 4.5-liter normally aspirated motor) and raced them the following year.

The BMW March team scored its most impressive weekend at Watkins Glen, with both cars on the front row and John Andretti/Davy Jones taking the overall win in convincing fashion. Photo: Tony Mezzacca

When BMW canceled its IMSA GTP program at the end of 1986, Gianpiero Moretti purchased the March 86G chassis and installed turbo-powered Buicks for the 1987 season. He co-drove here at Sears Point with Whitney Ganz. Photo: Richard Bryant

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” that tells the inside story of John Bishop’s life and how he created the world’s greatest sports car racing series. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

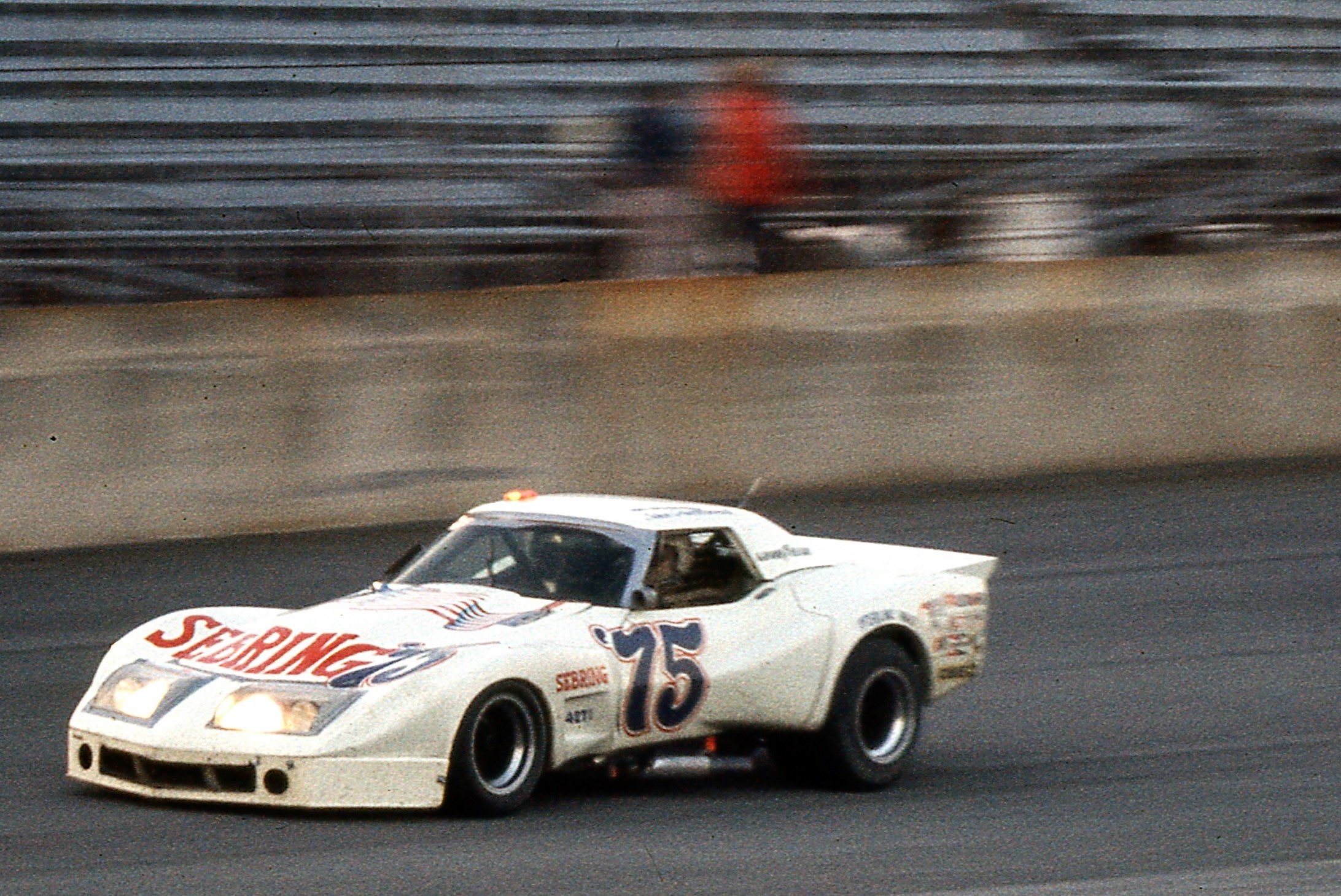

John Greenwood’s Corvette under braking for turn one during the 1975 24 Hours of Daytona, featuring his paint scheme promoting the 12 Hours of Sebring a few weeks later. Photo: Mark Raffauf

After a troublesome start at Daytona and subsequent upgrades to the car, the two-car factory BMW team showed up for the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1975 ready to mix it up. Australian touring car ace Alan Moffat supplemented the potent team of Hans Stuck, Sam Posey, Brian Redman, and Ronnie Peterson. The CSLs were now much improved and took advantage of specially crafted Dunlop tires. The old 5.2-mile Sebring course was a wide-open, hang-on-and-get-after-it circuit, where turns one and two were big, sweeping curves of concrete runway that required tremendous skill to navigate quickly without going off and hitting anything, including parked airplanes.

GT cars make their way down the massive back straight at Sebring in 1975. The runways of Sebring weren’t always as well marked as they are today. Nighttime navigation of the track was especially challenging. Photo: Mark Raffauf

In spite of John Greenwood’s Corvette taking pole, the BMWs stormed into an early lead. Within the first hour, Hans Stuck’s BMW was reported numerous times by corner workers at various locations not to have working brake lights. IMSA black-flagged the car to have its lights checked. Once in the pits, it was determined the lights were indeed working. A short time later the same reports started coming in: no brake lights, especially in turns one and two. The car was brought back in for another check. Again, all was good while stationary in the pits.

The winning factory BMW CSL of Hans Stuck, Sam Posey, Brian Redman, and Allan Moffat navigates the wide-open runways of Sebring in 1975 when Lockheed Constellations and Douglas DC-4s lined the course unprotected between turns one and two. Photo: Mark Raffauf

When the issue arose a third time, BMW team chief Jochen Neerpasch asked IMSA officials, “Where are the lights not working?” to which race control replied, “Various locations, including turns one and two.” Neerpasch responded with, “Oh, Hans does not use the brakes there at all!” With the stickier tires and improved performance, GT cars were now able to take turns one and two flat, or at least with a slight lift instead of braking. No one had ever seen that before, hence the confusion from the corner workers and race control.

The winners of the 1975 12 Hours of Sebring celebrate in Victory Lane. Sam Posey stands on top of the BMW CSL, flanked by Brian Redman (far right), Hans Stuck (seated next to Redman) and Allan Moffat (with daughter). Photo: Bill Oursler/autosportsltd.com

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” that tells the inside story of John Bishop’s life and how he created the world’s greatest sports car racing series. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

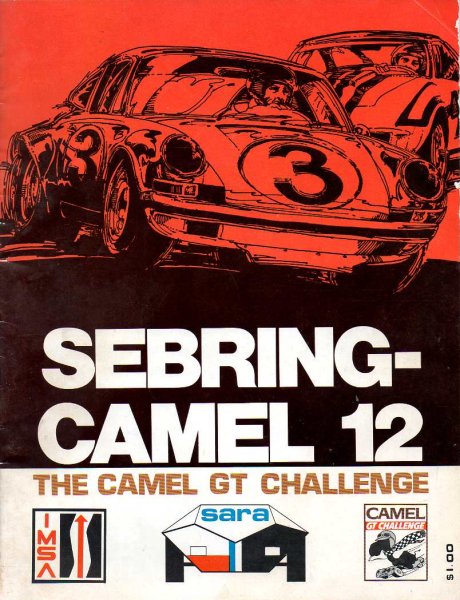

To many people, John Bishop became a savior in 1973. For twenty uninterrupted years, starting in 1952, the Sebring 12 Hour sports car endurance race for was held under the guidance of Alec Ulmann, one of the first members of the SCCA when it was founded in 1944. In 1950, Ulmann traveled to Le Mans to take in the sights and sounds of the 24-hour race. The experience inspired him to bring sports car endurance racing to the U.S., which he did with a six-hour race at Sebring later that year – the first such event held in America.

The Sebring track itself began life as Hendricks Army Airfield, a hastily built airport used during WWII as a training site for B-17 bomber crews. After the base was decommissioned in 1945, the airport was turned over to the local community. In the ensuing years, Ulmann convinced the airport authority to let him promote a series of races using the long runways and network of access roads as the track layout. As part of the agreement, one active runway remained in operation during the race.

The start of the first 12 Hours of Sebring in 1952. The event was the brainchild of Alec Ulmann, who organized the race on the decommissioned runways of a World War II B-17 training base. Photo: Sebring International Raceway Archives

Starting with the first 12 Hours of Sebring race in 1952, the event became a crown jewel on the international racing calendar, attracting the best and brightest drivers, manufacturers and race teams from around the world. The AAA acted as the sanctioning body for the first few years, until the organization quit the racing business after the now infamous Le Mans accident in 1955 that killed more than 80 spectators. After that, Alec and Mary Ulmann formed the Automobile Racing Club of Florida (ARCF) as an entity to produce and promote the race. Alec Ulmann was the vice president of the ARCF and also acted as race secretary for the event. The SCCA sanctioned the race from 1963 through 1972, with full backing from ACCUS and the FIA.

Nothing lasts forever, however. Years of use left the track surface broken, with large chunks of concrete regularly coming loose during events. The facilities were spartan for both competitors and spectators alike. Under pressure from the FIA to improve track safety for the ever-increasing speeds of new generation racing machines and to invest in better facilities for the growing crowds, the Ulmann family announced the 1972 running of the event would be the last. After 20 uninterrupted years, the Ulmann’s were tired and wanted to move on. Sebring appeared destined to become just another dusty footnote in racing history.

Recognizing an opportunity for IMSA to take over one of the world’s most recognized sports car events, Bishop approached Bill France Sr., the founder of NASCAR and investor in IMSA, with an idea for NASCAR to put up the money to save the Sebring race. France Sr. wasn’t convinced. According to Bishop: “Big Bill never understood why anyone would pay to see an event at Sebring, whose facilities, let’s say, fell far short of those at Daytona and Talladega.” Bishop couldn’t get his friend and partner to budge.

John Greenwood, on the right with Milt Minter, stepped up to bankroll the 1973 Sebring race, effectively saving the event. He would continue to be involved as a Sebring benefactor for years. IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

Then, providence intervened. Bishop happened to be talking with John Greenwood about Sebring on the pit wall at Daytona in January of 1973 and to his surprise, Greenwood offered to put up the money to save the event, including making some needed safety improvements to the track like building a higher wall separating the pits from the main straight. With only a few short weeks to get it all organized and done, the pressure and the stakes were high. But Bishop recognized an enormous opportunity to elevate IMSA’s status in the racing world.

The program cover for the first IMSA-sanctioned 12 Hours of Sebring in 1973. Sebring International Raceway Archives

Reggie Smith, the ex-secretary of the ARCF, now the ex-promoter of the Sebring race, started a new organization called the Sebring Automobile Racing Association, which later on affectionately became known as the Sebring City Fathers. SARA became the official promoter of the event. Greenwood put up the prize money and made safety improvements to the track. R.J. Reynolds was more than happy to have Sebring added to the Camel GT Series calendar, which was now in its second year.

IMSA was not yet a member of ACCUS, which turned out to be a good thing, as it was not under any pressure to adhere to FIA edicts or existing ACCUS rules preventing drivers from crossing over from one member’s sanctioned race to compete in another. For unknown reasons, the SCCA board of governors voted not to interfere with IMSA taking over the race. The Club appeared to have given up on Sebring. All of this meant IMSA had a free hand to sanction an event with an almost mystical international reputation and attract drivers from any race-sanctioning body on the planet.

The runways, taxiways and access roads at Sebring have always been a challenge for racers. The Camaro shared by Luis Sereix, Tony Lilly, and Dave Voder navigates the rough pavement. Note the orange cones intended to guide the competitors at night when Sebring was pitch black and especially tricky to navigate. autosportsltd.com

The 12 Hours of Sebring became the first IMSA Camel GT event of the 1973 season. With the help of RJR’s Joe Camel advertising campaign and renewed interest in the race, a good crowd showed up, ensuring Sebring would become a fixture on the IMSA calendar for many years to come. For many people who lived through the near-extinction of the Sebring race, Bishop was recognized as one of three heroes who stepped in at the last minute to rescue this iconic event. In recognition of their contributions, Bishop, Greenwood and Smith were later inducted into the Sebring Hall of Fame.

The winning Porsche Carrera RS of Peter Gregg, Hurley Haywood, and Dave Helmick at Sebring in 1973. The traditional colors of Brumos were not used as it was Dave Helmick’s car. autosportsltd.com

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” that tells the inside story of John Bishop’s life and how he created the world’s greatest sports car racing series. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

Former IMSA RS and GTU champion Don Devendorf (right) was the leader behind Electramotive Engineering, the team that fielded the all-conquering Nissan GTP ZX-T in the IMSA Camel GT Series in the last half of the 1980s. The team won the IMSA championship in 1988 and 1989. Photo: Peter Gloede

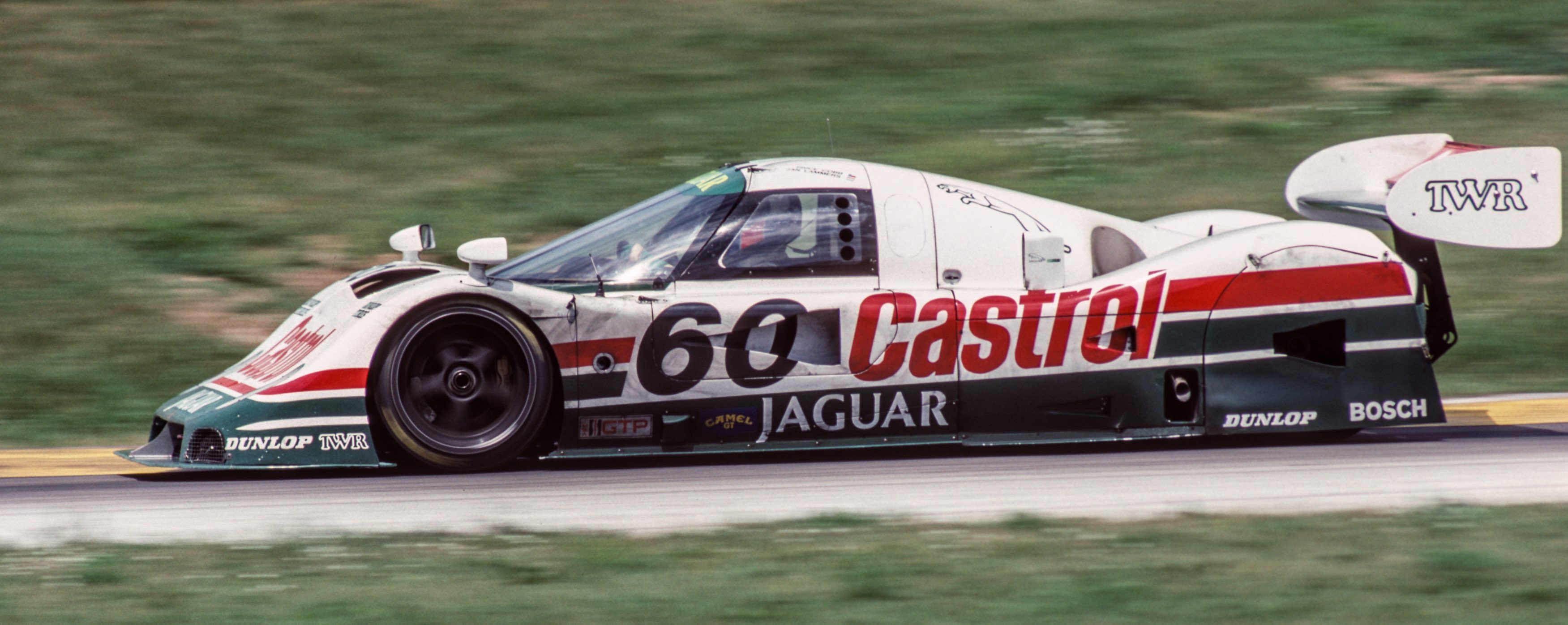

The TWR Racing Jaguar XJR-10 of Jan Lammers and Price Cobb led most of the way at Portland in 1989. Photo: Peter Gloede.

At the 1989 Portland round of the Camel GT Series, a titanic battle between the Nissans of Geoff Brabham and Chip Robinson and the two Castrol Walkinshaw Jaguars driven by Price Cobb/Jan Lammers and Davy Jones/John Nielsen lasted the entire distance. At the end of the race, an extraordinary sequence of events unfolded that created confusion and a tough decision for IMSA officials.

Jaguar ran two different cars in 1989—the XJR-9 (foreground) that featured a 7.0-liter, 12-cylinder, normally aspirated engine, and the new XJR-10 designed around a 3.0-liter, 6-cylinder twin-turbocharged motor. The cars are shown here at the previous round at Road America, sitting next to the Castrol transporter. Photo: Peter Gloede

Although the race was scheduled for 102 laps, for reasons never fully understood the local SCCA starter took it upon himself to throw the checkered flag on the 94th lap instead. About a third of the field took that flag, including the leaders – Cobb over Brabham by little more than one second. The teams knew the race was supposed to go 102 laps, so, for the most part, they told their drivers to keep right on racing. After a few cars took the checkered flag, IMSA race control realized what had happened, so they told the starter to pull in the checkered flag. The remaining cars flew by as if nothing had happened.

The Electramotive team was well known for their lightning-quick pit stops during their championship years, pictured here at Road America in 1989. Photo: Peter Gloede

Race control notified everyone on the radio that the race was proceeding to the full race distance. Five laps later, Brabham got by Cobb and took the second checkered flag after 102 laps. In the meantime, IMSA officials consulted the regulations and came to the decision that although the first checkered flag was flown early, it had to signify the end of the race: the event was over as of 94 laps and the win was awarded to Cobb/Lammers based on the standings at that time.

The now incensed Nissan team protested the results, which were held as provisional until the appeal could be heard by well-respected former driver John Gordon Bennett, IMSA’s commissioner. Bennett was the highest level of independent decision-making in IMSA’s appeal process. In other words, his decision would be final.

Realizing the intricacies of the situation, Bennett convened a panel of three other experts unaffiliated in any way with the parties in the dispute. The panel concluded that although incorrectly displayed, the sanctity of the checkered flag could not be disputed. IMSA was chastised by the panel for allowing the unfortunate flagging error to happen. The organization never again depended on local starters at races, instead bringing its own starter to every event. The Nissan team was disappointed, but the decision was accepted after one more minor protest.

At the next race in San Antonio, Nissan handed out a wonderfully designed lapel pin showing the number 83 car, a checkered flag, the words “Portland 1989” and a large screw going through the car, illustrating their feelings about what had happened in the Pacific Northwest.

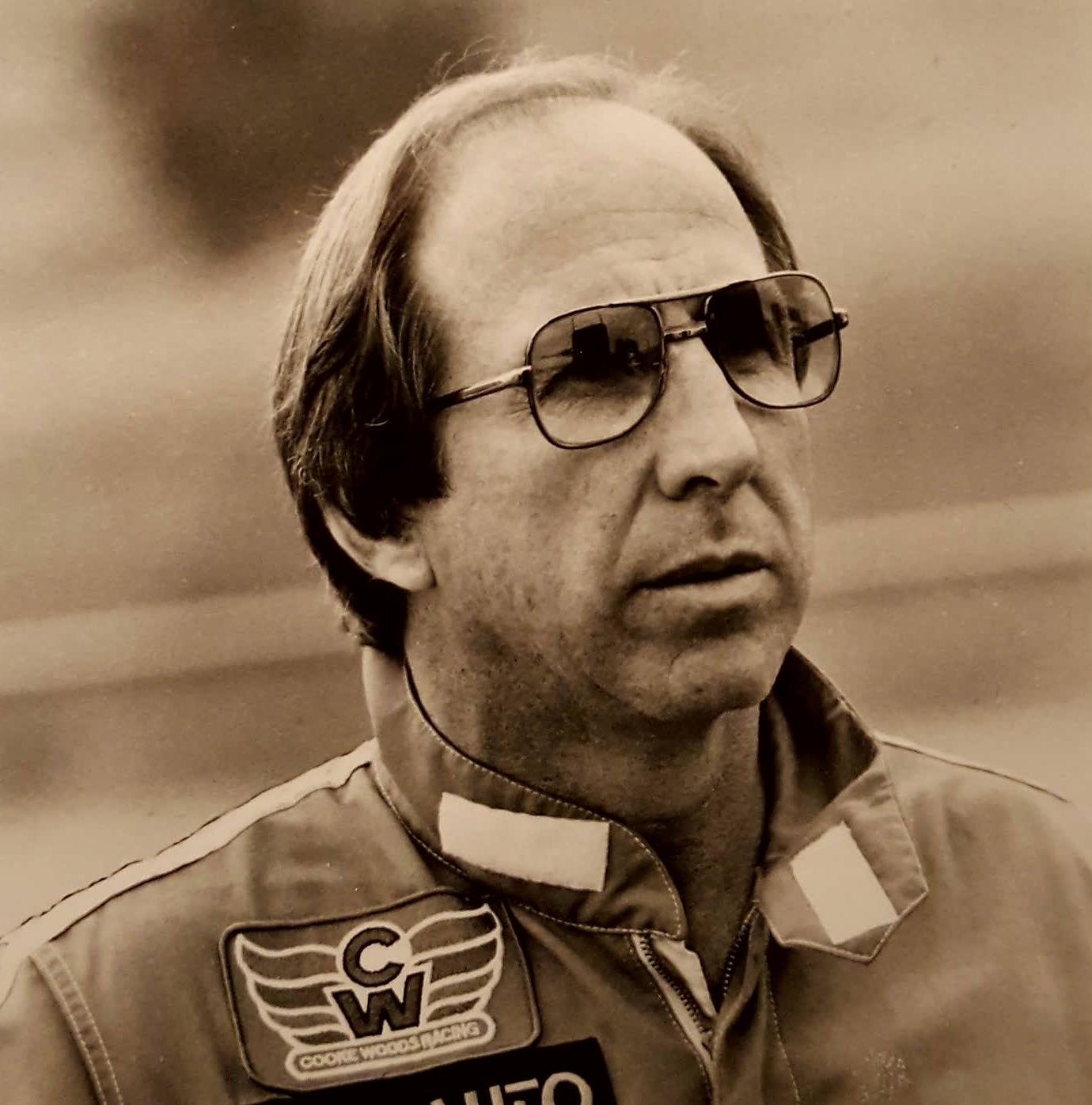

The 1981 24 Hours of Daytona shaped up to be another battle of Porsche 935s. The 935 had won the last three Daytona endurance races in a row starting in 1978. Although the 935 was based on a street 930, it was fast and reliable when properly prepared. Dick Barbour, after winning the IMSA championship with driver John Fitzpatrick in 1980, had stopped racing. That gave Bob Garretson the opportunity to continue with the same crew on his car in 1981 – a Porsche 935 (chassis 009 0030) which the team had built from a bare factory chassis in 1979. Bob had signed a new deal for 1981 to prepare the Cooke-Woods cars. This was a partnership between Roy Woods and Ralph Cooke. New Lola T600s had been ordered but would not be ready until later in the year, so the Porsche 935 would be run in the meantime. In any case, the Porsche would be more reliable for the 24 Hours of Daytona.

Team principal Bob Garretson just prior to the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1981.

The car would be driven at Daytona by Bob, Brian Redman, and Bobby Rahal. We seemed to struggle a bit in getting everything ready and prepared up to our normal standards. We were still putting the car together at the track, missing a few practice sessions. We had to send Brian Redman out to qualify using the session as a brake pad bedding session, so we ended up only 16th on the grid. Brian, however, was happy with the car and told us not to worry, all was well for the race.

The race featured no less than 15 or so Porsche 935s or derivatives, as well as the factory Lancia team, running the 2.0-liter MonteCarlos in the World Championship. At the green flag most took off at high speed, pushing like it was a one-hour sprint race. It wasn’t long before engines were blowing up left and right. Many of these cars came into the pits to change engines, which was legal back then. Several went through two engines.

One of the 2.0-liter turbocharged factory Lancia Betas that ran against an onslaught of Porsche 935s in the 1981 Daytona endurance classic. This one was driven by Formula One standout Ricardo Patrese, along with Hans Heyer and Henri Pescarolo. They would finish 18th. Photo: Martin Raffauf

In contrast, we ran to our pace and soon were running at the front from the 16th starting position. At one driver change in the early evening, Brian was furious with Bobby Rahal, as he had taken the lead during his stint; Brian told Bobby he was pushing too hard! Bobby was apologetic and said, “I didn’t pass anyone, they are all falling out.” Brian wandered off muttering, “It’s too early, it’s too early.”

The Garretson Porsche 935 on the tri-oval during practice for the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1981. Photo: Martin Raffauf

Around midnight, the Interscope 935 crashed with a backmarker and our car ran over some debris from the incident, which broke an exhaust pipe. This was quickly changed in the ensuing pit stop. By Sunday morning we were cruising and had a large lead of some 10-15 laps. Brian came in at about 6:45 am after a double stint, handed over to Bobby and asked, “Where’s breakfast?” Well, we said, nothing has been organized on that front yet. “Ok, he said, I’ll take care of it.” I remember thinking, how is he going to get breakfast? About 20 minutes later, Brian came back to the pits with bags of McDonald’s breakfast sandwiches. He had driven across the street to the McDonalds across from the speedway, still in his driving uniform, picked up food for the crew and had brought it back to the pits. He sat and ate with the mechanics in the pit, then went off to prepare for his next stint.

One of the friends of the team at this time, who was in our pit a lot, was Olivier Chandon, son of the French champagne house. By early Sunday, he began to get concerned, as he thought we would win, and there was crappy champagne on hand from the speedway for the Victory Lane celebration (in his view). The crew, of course, were not interested in any of this and ignored him, as we knew it was not “over until it’s over” as Yogi Berra used to say. We were just focused on making it to the end, not worrying about what kind of champagne we would drink, if any! In any case, Olivier was calling all over Daytona looking for Moet & Chandon but none was to be found. So, bless his soul, he jumped in a rental car, drove to Orlando, found the right stuff, and sped back to the circuit with the Moet & Chandon by noon or so.

The Garretson crew rushes towards the finish line to salute their car as it wins the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1981. That’s the author on the far right in the blue overalls, raising his red hat in celebration. Race organizers were not pleased with this behavior and outlawed such displays in the future due to safety concerns. Photo: Peter Gloede

We ran off the remaining laps without issue and won the race. An Egg McMuffin paired with Moet & Chandon; does it get any better? It was a grand celebration and Olivier was happy he could provide “the proper champagne!” Sadly, Olivier lost his life a few years later in a Formula Atlantic crash at West Palm Beach. But we always remember and salute the Moet & Chandon!

Victory Lane celebrations were sweet in 1981 with the right champagne! Photo: Peter Gloede

The following is an excerpt from the book “IMSA 1969-1989” written by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf, available from Octane Press or where ever books are sold.

The race-winning ANDIAL-powered, tube-frame Porsche 935 with full “Moby Dick” Le Mans bodywork at the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1983. The team of Wollek, Ballot-Lena, Foyt and Henn would go on to win the race. Photo: Bob Harmeyer

At the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1983, the Aston Martin brand was represented by two Nimrod V8 cars, one driven by A.J. Foyt and Darrell Waltrip and painted in Pepsi Challenger colors. On the pole was the ANDIAL tube frame 935, now converted to full “Moby Dick” long tail bodywork specially made for Le Mans. It was the monster of all 935s – the new body was on the same chassis that Rolf Stommelen had driven to the three straight long-distance victories in 1981. European veterans Bob Wollek and Claude Ballot-Lena were entered to co-drive with car owner and T-Bird Swap Shop entrepreneur Preston Henn.

Early on in the 1983 24 Hours of Daytona, the Swap Shop Porsche 935 leads the Pepsi-sponsored Aston Martin Nimrod GTP shared by A.J. Foyt and Darrell Waltrip. The Nimrod would drop out after 121 laps. Photo: Peter Gloede

Early retirements by JLP, Interscope, Bob Akin Racing and others kept the Swap Shop Porsche in close contact with first place through the first half of the race. After Foyt’s Nimrod also retired, Henn asked A.J. if he wanted to drive his car since it had a chance to win. Foyt agreed and got ready to climb in early Sunday morning at the beginning of what turned out to be an extended full course caution caused by heavy rain. The problem? Henn didn’t tell the other drivers.

Rain delayed the 1983 24 Hours of Daytona with a lengthy caution period and a red flag situation on Sunday morning. Photo: Bob Harmeyer

When Wollek pulled into the pits and opened the door to climb out, he saw Foyt on the pit wall dressed for battle and instantly realized what was about to transpire. Upset by Foyt taking over the car with a lead he had established and fearful the Texan would ruin the team’s race, Wollek tried to close the door and drive off. But the team physically pulled him from the car. Wollek was disgusted. He had put the car at the front and believed Henn was throwing the race away because Foyt had never driven the car before – nor driven at Daytona in the wet. But Foyt used a nearly two-hour full course caution period to learn the car and when the race was finally restarted, took off in the lead. Once again, Foyt affirmed his status as one of the all-time greats. The team went on to win the race.

Bob Wollek watches as A.J. Foyt climbs into the Swap Shop Porsche 935 early Sunday morning. Wollek’s body language tells a story in itself. Note the heavy media interest. Photo: Peter Gloede

All was forgiven in Victory Lane, but Wollek was still a bit perturbed with the whole episode. Reportedly Foyt turned to Wollek after the race and asked him; “How many times have you been to Le Mans?” Wollek answered; “At least a dozen times!” Foyt retorted: “How many times have you won?” Wollek, of course, had not won Le Mans. Foyt reminded him; “I’ve been to Le Mans once, and won.” They eventually became good friends and team mates, driving to victory together at Daytona and Sebring two years later in a Porsche 962.