The following is an excerpt from the book “IMSA 1969-1989” written by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf, available from Octane Press or where ever books are sold.

The 1976 24 Hours of Daytona was possibly the most unusual Camel GT race ever run. A record 72 entries showed up and the event had a relatively normal first 15 hours. After racing through the night, the BMW CSL of Peter Gregg and Brian Redman held an enormous 17-lap lead as the sun came up Sunday morning. But when Redman stopped for fuel and tires just after 9:00 a.m., the car misfired and then stalled coming out of the pits. Stranded out on the course, Redman tried to get the car re-fired, to no avail. He eventually borrowed jumper cables and a battery from some helpful fans beside the track and somehow managed to coax the BMW back to life and limped back to the pits. In the meantime, nine of the top ten cars in the race began to suffer the same symptoms, they were coughing and coming to a halt after refueling. The culprit? Water in the gasoline.

Brian Redman’s stricken BMW CSL during the 1976 24 Hours of Daytona, after stalling out on course with water tainted gasoline. Redman is trying to get it restarted with coaching from his crew, who were not allowed to touch the car. Photo credit: ISC Archives & Research Center/Getty Image

The decision was made to red flag the race an hour after the problems first started appearing; IMSA wanted to avoid having the entire field suffer the same fate. After some investigation, it was determined that the affected teams had all been serviced by a single gasoline truck. Somehow, water had been introduced into the fuel carried by that one truck.

John Bishop conferred with Chief Steward Charlie Rainville and the decision was made to roll back timing and scoring to the last complete lap before the problem first emerged at 9:01 a.m. on Sunday morning. That call was cheered by some teams and derided by others, depending on whether their car had been felled by the bad fuel or not.

As John later recalled: “Rolling back scoring of the race seemed like the only fair thing to do. Some of the teams that had dodged the bad fuel issue were upset, but you have to remember that this was an extraordinary, unprecedented situation that was out of the control of even the most well-prepared teams or the track.”

By the time a replacement truck with fuel arrived from Jacksonville, 90 miles away, two and a half hours had elapsed. Normally, teams were not allowed to work on their cars under red flag conditions, but in this case, IMSA officials told everyone they could use the time to purge their fuel systems to get running again. Those with foam-filled fuel cells were doomed, however, because the water had been absorbed into the lining of the cell.

The BMW teams are serviced in the pit lane at Daytona in 1976 after the 24 hour race was red flagged. Teams were allowed to work on their cars to purge their fuel tanks, which had become contaminated with water. Red and green barrels were used to indicate which contained “good” and “bad” fuel. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com

The #14 Al Holbert/Claude Ballot-Lena Porsche Carrera RSR is serviced during the lengthy red flag due to water contaminated gasoline during the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1976. The pair would go on to finish second in the race. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com

Once their fuel system had been cleaned, Redman and Gregg resumed the race with their 17-lap lead intact, almost three hours after the race had been red flagged and almost four hours since the last officially scored lap. Just 29 cars restarted the race, the rest having fallen out prior to the fuel issue or having been done in by the tainted gasoline. The duo of Redman and Gregg went on to win by 14 laps over Al Holbert and Claude Ballot-Lena in a Carrera RSR. It would be the third 24 Hours of Daytona victory for Gregg.

The winning BMW CSL of Brian Redman and Peter Gregg at the 1976 24 Hours of Daytona. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com

The second place Porsche Carrera RSR of Al Holbert and Claude Ballot-Lena flies through the tri-oval in the rain at the 1976 24 Hours of Daytona. Photo credit: International Motor Racing Research Center/IMSA Collection

Author: Martin Raffauf

All photos: Jerry Woods

Dick Barbour raced at the 24 Hours of Le Mans as an entrant for the first time in 1978, where he entered two Porsche 935’s in the special IMSA class at the classic French enduro. Barbour had started racing in IMSA in 1977 after having bought one of the original ten Porsche 934/5 models offered by the factory for IMSA racing that year. He ran some of the IMSA races with mixed success, but towards the end of the season, he and Bob Garretson signed an agreement that committed Garretson Enterprises to prepare Dick’s car(s) for the 1978 season.

Garretson Enterprises was an independent Porsche repair shop in Mountain View, California that had made a name for themselves in 1977 by preparing Walt Maas’ IMSA GTU championship-winning Porsche 914-6. The team entered eleven races that year and won eight of them, and finished second, third and fourth in the others, winning the championship over the factory Datsun 240Z of Sam Posey run by Bob Sharp. They had also prepared the winning car at the 1976 Pikes Peak hill-climb, a Porsche-powered buggy for Rick Mears.

Dick was looking to expand in 1978, so he ordered a new 935-78 (77A) for Daytona. His old 934/5 from 1977 would need some work and investment to update it to full 935 specifications. With Johnnie Rutherford and Manfred Schurti as co-drivers, he finished second overall at Daytona with the new car, after being delayed by a blown tire in the banking which lost a lot of time for repairs. For Sebring, two cars were entered, and although Dick’s main car faltered when a shock broke and punctured an oil line, the second car driven by Bob Garretson, Brian Redman and Charles Mendez (the race promoter), won the race. That car was immediately sold to John Paul Sr. after Sebring.

After Sebring, where I started with the team, we started preparing for two more US races, Talladega and Laguna Seca, then Le Mans. The second-place Daytona car (serial number 930 890 0033) ran at Talladega and finished third with Dick and Johnnie Rutherford driving. For Laguna Seca, we entered two cars, one for Dick, who finished sixth and one for Bob Bondurant (which was the updated 934/5) who ended up seventeenth. Then came the big push to get everything ready for Le Mans. In those days transportation for the car was usually done by boat, so a long lead time was required.

Although I was working with the team quite a bit by then, I was not going to the races (except for Laguna and Sears Point), as the traveling schedule had already been determined. I helped get everything prepared and loaded and then wished the team well. Steve “Yogi” Behr from New York (an IMSA racer from time to time) came and drove one of the trucks back to New York for us to get it to the ship, as there were no other people available to make the drive.

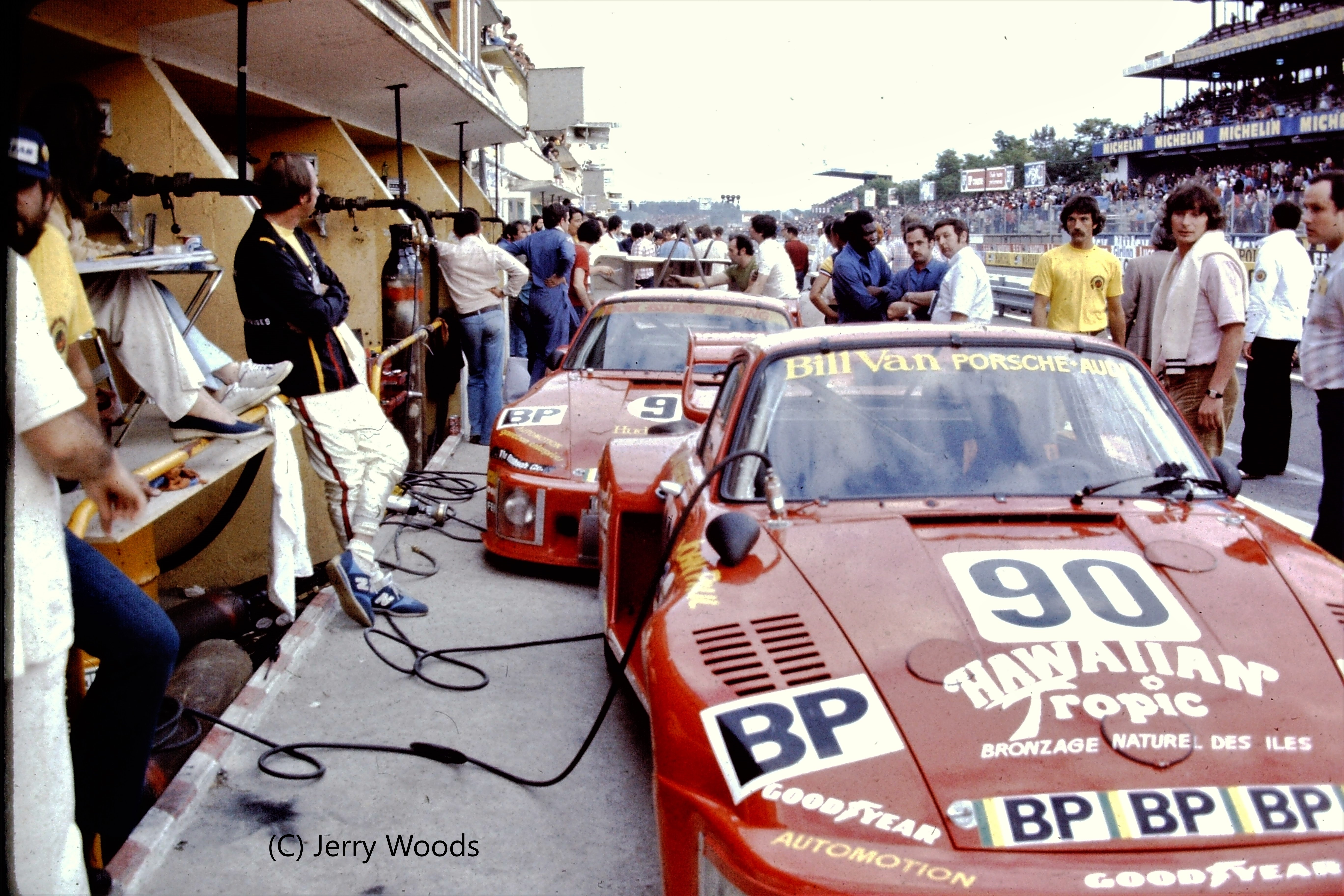

Dick had ordered a brand- new twin turbo 935 from the Porsche factory for the race. Gary Evans, the team manager, had gone over to Germany to order it earlier in the year (serial number 930 890 0024). Gary and Jerry Woods went to the factory to take delivery before the Le Mans race. It was then delivered to the track by Porsche with the rest of their cars. It would run as #90, and be driven by Dick, Brian Redman, and John Paul Sr. The second car, which we had prepared in California, was a Porsche 935 (serial number 930 890 0033). This 935 was a single turbo model and would be driven by Bob Garretson, Bob Akin, and Steve Earle.

Dick Barbour Racing picks up a brand-new Porsche 935 from the factory just prior to the 1978 24 Hours of Le Mans. Gary Evans at Left, Bob Garretson and Sharon Evans at right.

The majority of the team had arrived the weekend before and set up in the Le Mans paddock. Several of the team stopped on the way and watched the Spanish Grand Prix at Jarama. At the Madrid airport, they ran into none other than Bill France Sr. of NASCAR, who gave them directions to the circuit. Ron Trethan, Greg Elliff, Brian Carleton, and Alan Brooking watched Mario Andretti win the Spanish Grand Prix in a Lotus 79. Many years later, Greg Elliff would restore the very same Lotus 79 for Duncan Dayton. At the race, they ran into Bill Broderick (the hat swap guy in victory lane!) from Union Oil (NASCAR). After the race, at the airport, all the drivers had already arrived from the track via helicopter. They had a beer with Jody Scheckter while waiting for the plane to France. By the time they got to the team hotel in Pontvallain France, it was very late and the place was already shut down as everyone had gone to bed. They slept on the sidewalk in front of the hotel and were woken early by the street sweepers. I guess that’s what happens when you travel from Mountain View, California to Pontvallain France for the first time! Pontvallain was just not set up for “late arrivals.”

Dick Barbour Racing crew gets set up in the grass paddock at Le Mans in 1978. As newcomers, we did not get prime paddock space in 1978.

The Le Mans circuit back then was very different from today. The Mulsanne had no chicanes, and the pits were old, and quite decrepit. The signal pits were at the far end of the circuit, many miles away at the Mulsanne corner. Radios back then were problematic, and in any case, the American radios did not work too well in France and were technically illegal to use, as you were supposed to have a French license to use any radios. Communications to the signal pits were via old crank up phones on the wall in the pit boxes. Paddock and team working conditions, were basic at best. Much of the paddock was not even paved, and as “newcomers”, the team got a prime grass corner in the back. The hotel was a small one in the town of Pontvallain which was well to the south of Le Mans, about a one hour drive.

The car as delivered by Porsche, needed some work to become IMSA legal as the rules for FIA Group 5 and IMSA were slightly different. IMSA rules required windshield retaining tabs, rear window straps, and a driver’s window net. New front air dams that had been built in California were fitted. These had been built by Jeff Lateer, and contained two headlights per side, thereby alleviating the need for the night hood mounted extra lights (lessening drag on the Mulsanne). The delivered drilled brake rotors were removed and replaced with longer lasting solid rotors.

Both Dick Barbour cars sit in the pits at Le Mans prior to the start of the 24-Hour classic.

Both cars were entered in the IMSA class, along with a bunch of Ferrari 512BBs, a few RSRs, one BMW CSL, and Brad Frisselle’s Monza. There were Group 6 prototypes from Both Porsche (936) and from Renault, as well as Mirage. These would be the cars to beat for overall victory. There were also quite a few Group 5 Porsche 935s and Group 4 Porsche 934s as well as 2.0-liter sports cars. All the 935s ran the 3.0- liter engine, some twin turbo, some single, except for the 935-78 from the factory which ran a 3.2 engine with water cooled heads. All the Group 5 935s weighed less than the IMSA version, as we had to run at the IMSA minimum weights to run in the class.

Both our cars qualified without difficulty. Redman got the pole in the IMSA class with a 3:52.6, Dick did a 3:56.6, and John Paul Sr. a 4:02. Bob Garretson qualified the #91 at 4:05, Bob Akin at 4:09 and Steve Earle at 4:13. Rolf Stommelen set a blistering time in the 935-78 of 3:30.9 to start third overall behind Ickx in the 936-78 at 3:27.6, and Depallier in the Renault at 3:28.4. The battle for the IMSA class would come down to our two cars, and most likely the Ferraris of Charles Pozzi and NART. Dick, having finished second at Daytona, was in an advantageous position to win the Daytona-Le Mans trophy for 1978. This trophy was awarded to the driver/team who did the best in the two races combined. Since the Brumos (Peter Gregg) team, which won Daytona, was not running at Le Mans, Dick just had to finish well up and he would get that trophy. That was a secondary goal of winning the IMSA class.

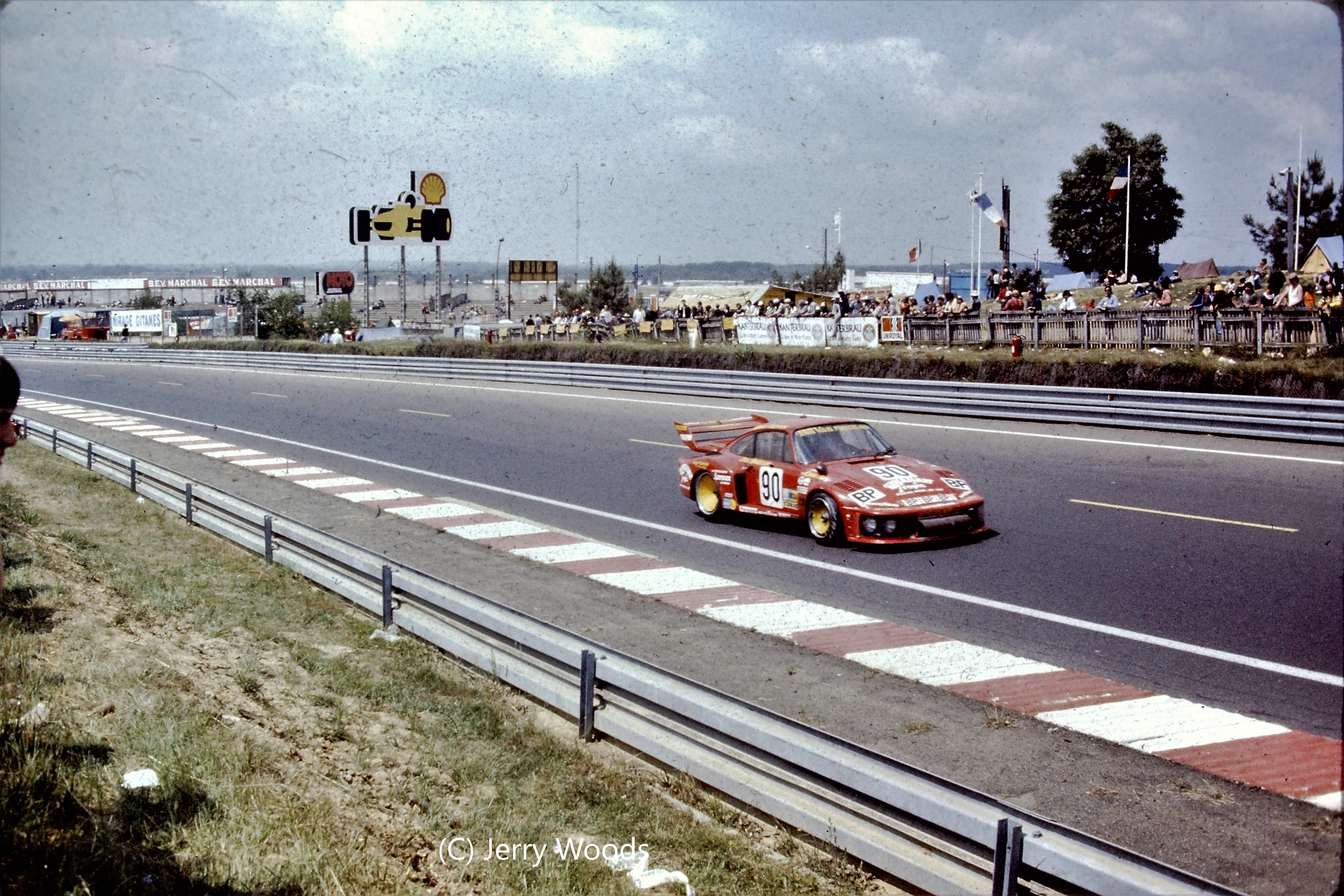

The number 90 Porsche 935 at speed at Le Mans in 1978. The car was shared by Dick Barbour, Brian Redman, and John Paul, Sr. and would win the special IMSA class that year.

The race started well enough. The strategy was to drive conservatively, finish, and win the class. Starting in the early stages, the #90 led the class and ran like clockwork. The #91 had a few issues, including troubles changing brake pads and a crash by Steve Earle, which required new front fenders and air dam. Around 3:50 am Sunday, #91 had an issue with the exhaust system, and 14 minutes were lost, but the car was still running. At 4:55 am Sunday, Bob Garretson went off the road at the Mulsanne kink, vaulted end over end on the side of the track on driver’s left. He doesn’t really remember what happened, and although he was dazed, he walked away from the crash. About the only thing he recalled was that the door was so smashed he had to crawl out thru the windscreen area. The windshield was gone completely. The car was pretty much destroyed. Brian Redman stopped at the site in the #90 car, checked to see if Bob was ok, then pitted to give a report to the rest of the team. Several of the crew went out to the crash site once it became daylight, and found Bob’s glasses in the dirt by the car.

The number 91 Porsche 935 wasn’t so fortunate, having crashed at high speed on the Mulsanne straight in the middle of the night. Driver Bob Garretson escaped unhurt, although he had to crawl out the hole the windshield used to occupy. The car was almost completely a write-off.

By the time we got it back to the shop in California, about all that was salvageable were a few gauges from the dashboard, some of the engine parts, and some of the gearbox parts. Most of the suspension, bodywork, chassis, roll cage etc. was all trash.

The #90 car ran trouble-free, just making normal pit stops for fuel, tires and changing of brake pads. The only real issue occurred at one point when team manager Gary Evans went looking for Brian Redman to get him ready for the next pit stop. He was getting worried when he didn’t find him in any of the driver caravans, which were all full of sponsors and others who weren’t supposed to be in there. Eventually, he was found sleeping in the canvas tire slings in the truck – disaster averted.

Brian Redman catches a nap between stints. Everyone, even the drivers, had to grab sleep when and where you could find it.

Since John Paul Sr. was driving with us, he brought his main mechanic, Graham Everett along. He and Greg Elliff changed the brake pads and did it well. According to Le Mans records, not one stop for this car was longer than two minutes. Even the Porsche factory guys on the 936 next door to us were impressed, as the #90 car was changing brake pads quicker than they were. Most of the race we were in a battle with the Group 5 leader, which was the Kremer car of our IMSA buddies Jim Busby, Rick Knoop, and Chris Cord. In the end, we finished fifth overall and won the IMSA class, and they finished sixth overall and won the Group 5 class. The Porsche factory at Werks 1 – Zuffenhausen had certainly done an outstanding job building 930 890 0024. Not one issue, and a class winner, first time out. The drivers did an excellent job and avoided any on-track issues, and the pit work was exemplary.

Dick Barbour had accomplished both goals – winning the IMSA class and winning the Daytona-Le Mans trophy for 1978. After that experience, he was hooked and would return to Le Mans again in 1979. But that’s another story.

Reprinted with Permission from PorscheRoadandRace (www.PorscheRoadandRace.com)