In mid-November 1992, thanks to leading 103 laps in the Hooter’s 500 at the Atlanta Motor Speedway, Alan Kulwicki was able to secure the five bonus points for leading the most laps in the race, which would, in turn, then allowed him to finish second to Bill Elliott and yet still secure the Winston Cup title. Bill Elliott, driving for Junior Johnson, led for 102 laps, the difference of that one lap deciding the championship in the favor of Kulwicki, despite Elliott winning for the fifth time that season.

It was, of course, somewhat more complicated than that. There were, after all, twenty-eight events in NASCAR’s Winston Cup Series prior to the Hooter’s 500 in November. The Bill Elliott versus Alan Kulwicki battle for the title as the race wound down was not necessarily what might have been expected when the green flag dropped to start the race, which was, incidentally, the last for Richard Petty and the first Winston Cup start for Jeff Gordon. Coming into the race, the points leader was Davey Allison, not Elliott. The lead for the championship had changed after the previous event, the Pyroil 500 at the Phoenix International Raceway, two weeks previously.

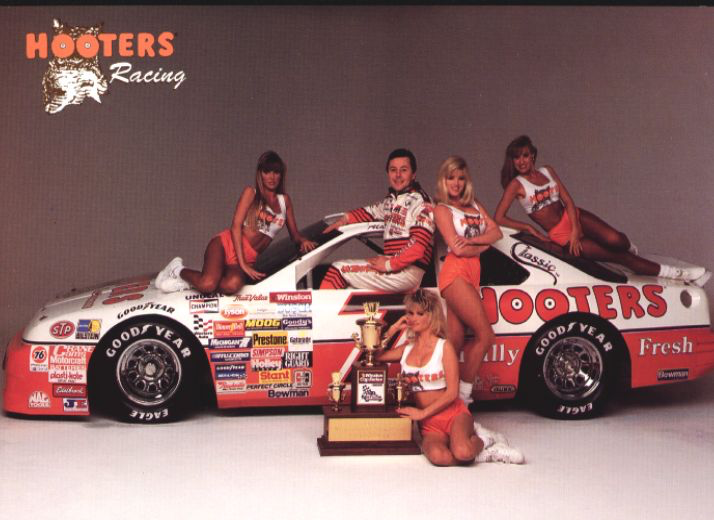

Alan Kulwicki, during the 1992 season. Photo: Hooter’s

Davey Allison held the lead in the points standings for much of the season before Elliott moved past him at the Miller 500 at the Pocono International Raceway in mid-July. Elliott was about to take a slim nine-point lead in the standings thanks to Allison having a massive crash that left him with a broken right collarbone, forearm, and wrist. That Allison was not injured more severely was little short of a miracle given that his Ford Thunderbird rolled eleven times, slammed into the guardrail and ultimately came to rest on its roof.

At the next race, the Diehard 500 at the Talladega Superspeedway, using Bobby Hillin Jr. as a relief driver to be credited for finishing third, the injured Allison managed to take a one-point lead over Elliott. However, from the Budweiser at the Glen in August until the Phoenix race, Bill Elliott held the lead in the Winston Cup standings. It was not without problems, however. He blew an engine at the Goody’s 500 at Martinsville and suffered with an ill-handling car during the Tyson 400 at North Wilkesboro, relegating him to a 26th place finish. He then hit the guardrail and broke a sway bar during the Mello Yello 500 at the Charlotte Motor Speedway, spending eighteen laps in the pits for repairs. But after the AC-Delco 500 at Rockingham, with a sixth-place or better finish at the remaining two events on the calendar (Phoenix and Atlanta), Elliott was in a position to clinch the Winston Cup championship.

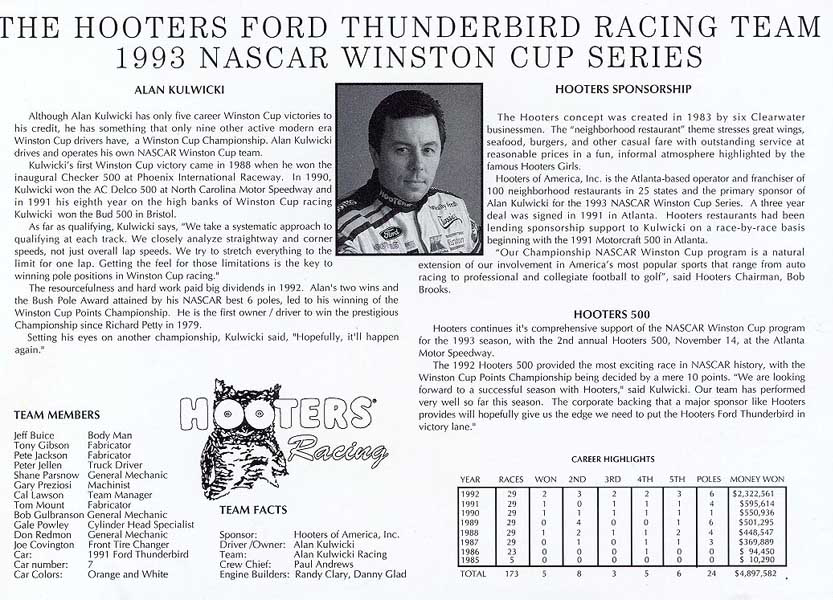

Tribute Card issued by Hooter’s after Alan Kulwicki won the 1992 Winston Cup Championship that was used during autograph sessions. Credit: Hooter’s

At Phoenix, Elliott’s Thunderbird cracked a cylinder head and started overheating, relegating him to a thirty-first place finish. This allowed Allison to retake the points lead with his win. A fourth-place finish by Kulwicki moved him past Elliott and into second place in the standings. As they headed towards the season finale, Allison was now the leader, with Kulwicki thirty points back, and Elliott forty points in arrears. Also within striking distance, mathematically or at least possibly or theoretically, were Harry Gant, Kyle Petty, and Mark Martin. The latter three would require some very serious problems among the top three given that Gant and Petty were over fifty points behind.

What all this meant was that to be the 1992 Winton Cup champion, Davey Allison simply needed to finish fifth or better to ensure the title regardless of whatever the others might end up doing. Plus, he had a thirty point buffer over Kulwicki with an additional ten points on top of that over Elliott. In other words, it seemed quite reasonable that Davey Allison would emerge as the 1992 champion, especially in light of the difficulties facing Kulwicki and Elliott, not to mention Allison coming off a victory at Phoenix, having the momentum that success creates going into the finale.

The Atlanta race was run under a points schedule that was put in place by NASCAR beginning with the 1975 season. It replaced a series of point systems that were often confusing to fans and teams alike. Until the 1968 season, the Grand National series, as it was then known, used a combination of prize money and distance to determine the points awarded for an event. In 1964, for example, points were awarded using sixteen different schedules based upon the prize money posted and the distance of an event. From 1968 60 1971, this somewhat chaotic system was replaced by a very simple three-tiered system: points were awarded for events less than 250 miles, those between 251 and 399 miles, and those 400 miles or longer.

In 1972 and 1973, points were awarded based upon the finishing position and then with additional points given according to the number of laps completed in a race. If that system wasn’t enough of a bookkeeping nightmare, in 1974 NASCAR managed to outdo itself: Winnings from purse posted for an event, with qualifying and contingency awards not counting, multiplied by the number of races started, with the resulting figure divided by 1,000 determined the number of points earned in the championship. Needless to say, it turned out to be so hopelessly difficult to compute that even the teams were more often than not often confused trying to figure it out. Although the 1974 system has been the subject of a massive case of organizational amnesia in Daytona Beach, the system was clearly intended to reintroduce one of the major components of how NASCAR – and Big Bill France in particular – weighed the early points system by giving emphasis to the prize money being awarded.

In 1975, Bob Latford – usually referred to as a NASCAR “historian,” but in reality, a public relations flack for the organization who also just happened to be a high school classmate of Bill France, Jr. – devised a system that was used from 1975 through the 2003 seasons. It awarded points on a sliding scale in increments of five, four, three, two, and one down to fifty-fourth place, beginning with 175 points for first place. Points were awarded for an event regardless of the distance or the purse that was posted. Five bonus points for leading a lap with an additional five points for the driver leading the most laps in a race.

This meant that a driver finishing second in a race, earning 170 points, could earn five more points for leading a lap, and another five points for leading the most laps. In other words, with the winner getting an automatic additional five points thanks to leading a lap, earning 180 points, it also meant that a driver finishing second, 170 points, could equal the points awarded to the winner by leading the most laps in a race, therefore adding ten bonus points to his score, also earning 180 points.

It was this quirk in the points system that came into play as events played out during the Hooters 500 at Atlanta in 1992. As mentioned, although it was theoretically possible for Harry Gant, Kyle Petty or Mark Martin to win the championship, this meant that Davey Allison, Alan Kulwicki, and Bill Elliott all needed to fall out of the race very early on, earning very few points, and that one of the trio needed to win the race. As it turned out, Martin retired with engine trouble and neither Gant or Petty were much of a factor at the end, finishing thirteenth and sixteenth, respectfully.

Needing only to finish fifth or better to wrap up the championship regardless of what Kulwicki or Elliott did, Davey Allison’s championship hopes ended less than fifty laps from the end. Running in the top five most of the time, making sure to gain five bonus points by leading a lap thanks to pitting late during the third caution period, Allison’s Thunderbird was shoved into the wall by the Chevrolet of Ernie Irvan when the Morgan-McClure team driver lost control in the fourth turn. With the damage to the car such that Allison was out of the race, the attention now shifted to the cat-and-mouse game that the Junior Johnson and Kulwicki teams had been playing just in case something like this happened.

The decision by Kulwicki’s crew chief, Paul Andrews, to stay out an extra lap while leading, ensuring that the five bonus points for leading the most laps was critical for Kulwicki. This meant that by finishing second, even if Elliott won the race and collected 180 points, that Kulwicki’s second-place points total of 170 would have an additional ten points added, therefore equaling Elliott’s 180 points. Had Elliott and Kulwicki finished first and second, but with Elliott collecting the five bonus points for leading the most laps, his 185 points and Kulwicki’s 175 points would have resulted in a tie: 4,073 points each. With the tiebreaker being the total number of wins in the season, Elliott would have become the 1992 Winston Cup champion, with his five wins against Kulwicki’s two wins.

Alan Kulwicki’s Ford Thunderbird, with Ford’s permission, ran the race as an “Underbird,” with a cartoon Mighty Mouse on board also adding emphasis to the team’s position as the underdog in the championship fight. That Alan Kulwicki Racing defeated the Junior Johnson team, which had attempted to hire him at one point, also meant that by earning the 1992 title Kulwicki also ended up as the last owner-driver to do so. Alas, on 1 April 1993, Kulwicki and three others died when an aircraft owned by the Hooters restaurant chain crashed on its way to the Bristol International Raceway. Later that year, on July 12, 1993, Davey Allison crashed his Hughes 369 HS helicopter while landing at the Talladega Superspeedway, dying the following day.

Alan Kulwicki hoisting the Winston Cup Championship Trophy, at the conclusion of the Hooter’s 500, Atlanta on November 12, 1992. Photo: Racing One/Getty Images.

If the legacy of the 1992 fight for the Winston Cup ultimately ended in tragedy for Alan Kulwicki and Davey Allison, there were other notable aspects to the season as well. One of them was the debut of Joe Gibbs Racing, a single-car team with Dale Jarrett driving a Chevrolet Lumina sponsored by Interstate Batteries. The addition of a lighting system for The Winston, the series all-star event held at the Charlotte Motor Speedway was not only a spectacular success at the time, but a harbinger of the future that the Daytona added later for racing under darkness.

There was also the deaths of Anne and Bill France, Sr. in January and June, respectively. Although Big Bill had turned over the helm of NASCAR to his son, Bill Jr. in 1992, Big Bill’s presence still loomed over the organization. His death was literally the end of an era for NASCAR, the links to its origins beginning to fade and its mythology becoming even more embedded in American folklore and the culture of motorsport. That said, it was Anne France who was possibly the real reason that NASCAR both survived and literally prospered: it was Mrs. France who ran the financial side of the family business, who kept the books and an eye on the real moneymaker for NASCAR, the Competition Liaison Bureau, the entity to which the promoters posted their purses so as to guarantee that the money would be available at payout time.

That, of course, is another story…